“It is all a bit of a mess. It used to be simple. Now it is complicated.” This was the conclusion of Mark Carden, the coordinator of the Researcher to Reader conference after two days of discussion, debate and workshops about scholarly publication..

The conference bills itself as: ‘The premier forum for discussion of the international scholarly content supply chain – bringing knowledge from the Researcher to the Reader.’ It was unusual because it mixed ‘tribes’ who usually go to separate conferences. Publishers made up 47% of the group, Libraries were next with 17%, Technology 14%, Distributors were 9% and there were a small number of academics and others.

In addition to talks and panel discussions there were workshop groups that used the format of smaller groups that met three times and were asked to come up with proposals. In order to keep this blog to a manageable length it does not include the discussions from the workshops.

The talks were filmed and will be available. There was also a very active Twitter discussion at #R2RConf. This blog is my attempt to summarise the points that emerged from the conference.

Suggestions, ideas and salient points that came up

- Journals are dead – the publishing future is the platform

- Journals are not dead – but we don’t need issues any more as they are entirely redundant in an online environment

- Publishing in a journal benefits the author not the reader

- Dissemination is no longer the value added offered by publishers. Anyone can have a blog. The value-add is branding

- The drivers for choosing research areas are what has been recently published, not what is needed by society

- All research is generated from what was published the year before – and we can prove it

- Why don’t we disaggregate the APC model and charge for sections of the service separately?

- You need to provide good service to the free users if you want to build a premium product

- The most valuable commodity as an editor is your reviewer time

- Peer review is inconsistent and systematically biased.

- The greater the novelty of the work the greater likelihood it is to have a negative review

- Poor academic writing is rewarded

Life After the Death of Science Journals – How the article is the future of scholarly communication

Vitek Tracz, the Chairman of the Science Navigation Group which produces the F1000Research series of publishing platforms was the keynote speaker. He argued that we are coming to the end of journals. One of the issues with journals is that the essence of journals is selection. The referee system is secret – the editors won’t usually tell the author who the referee is because the referee is working for the editor not the author. The main task of peer review is to accept or reject the work – there may be some idea to improve the paper. But that decision is not taken by the referees, but by the editor who has the Impact Factor to consider.

This system allows for information to be published that should not be published – eventually all publications will find somewhere to publish. Even in high level journals many papers cannot be replicated. A survey by PubMed found there was no correlation between impact factor and likelihood of an abstract being looked at on PubMed.

Readers can now get papers they want by themselves and create their own collections that interest them. But authors need journals because IF is so deeply embedded. Placement in a prestigious journal doesn’t increase readership, but it does increase likelihood of getting tenure. So authors need journals, readers don’t.

Vitek noted F1000Research “are not publishers – because we do not own any titles and don’t want to”. Instead they offer tools and services. It is not publishing in the traditional sense because there is no decision to publish or not publish something – that process is completely driven by authors. He predicted this will be the future of science publishing will shift from journals to services (there will be more tools & publishing directly on funder platforms).

In response to a question about impact factor and author motivation change, Vitek said “the only way of stopping impact factors as a thing is to bring the end of journals”. This aligns with the conclusions in a paper I co-authored some years ago. ‘The publishing imperative: the pervasive influence of publication metrics’

Author Behaviours

Vicky Williams, the CEO of research communications company Research Media discussed “Maximising the visibility and impact of research” and talked abut the need to translate complex ideas in research into understandable language.

She noted that the public does want to engage with research. A large percentage of public want to know about research while it is happening. However they see communication about research is poor. There is low trust in science journalism.

Vicki noted the different funding drivers – now funding is very heavily distributed. Research institutions have to look at alternative funding options. Now we have students as consumers – they are mobile and create demand. Traditional content formats are being challenged.

As a result institutions are needing to compete for talent. They need to build relationships with industry – and promotion is a way of achieving that. Most universities have a strong emphasis on outreach and engagement.

This means we need a different language, different tone and a different medium. However academic outputs are written for other academics. Most research is impenetrable for other audiences. This has long been a bugbear of mine (see ‘Express yourself scientists, speaking plainly isn’t beneath you’).

Vicki outlined some steps to showcase research – having a communications plan, network with colleagues, create a lay summary, use visual aids, engage. She argued that this acts as a research CV.

Rick Anderson, the Associate Dean of the University of Utah talked about the Deeply Weird Ecosystem of publishing. Rick noted that publication is deeply weird, with many different players – authors (send papers out), publishers (send out publications), readers (demand subscriptions), libraries (subscribe or cancel). All players send signals out into the school communications ecosystem, when we send signals out we get partial and distorted signals back.

An example is that publishers set prices without knowing the value of the content. The content they control is unique – there are no substitutable products.

He also noted there is a growing provenance of funding with strings. Now funders are imposing conditions on how you want to publish it not just the narrative of the research but the underlying data. In addition the institution you work for might have rules about how to publish in particular ways.

Rick urged authors answer the question ‘what is my main reason for publishing’ – not for writing. In reality it is primarily to have high impact publishing. By choosing to publish in a particular journal an author is casting a vote for their future. ‘Who has power over my future – do they care about where I publish? I should take notice of that’. He said that ‘If publish with Elsevier I turn control over to them, publishing in PLOS turns control over to the world’.

Rick mentioned some journal selection tools. JANE is a system (oriented to biological sciences) where authors can plug in abstract to a search box and it analyses the language and comes up with suggested list of journals. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) member list provides a ‘white list’ of publishers. Journal Guide helps researchers select an appropriate journal for publication.

A tweet noted that “Librarians and researchers are overwhelmed by the range of tools available – we need a curator to help pick out the best”.

Peer review

Alice Ellingham who is Director of Editorial Office Ltd which runs online journal editorial services for publishers and societies discussed ‘Why peer review can never be free (even if your paper is perfect)’. Alice discussed the different processes associated with securing and chasing peer review.

She said the unseen cost of peer review is communication, when they are providing assistance to all participants. She estimated that per submission it takes about 45-50 minutes per paper to manage the peer review.

Editorial Office tasks include looking for scope of a paper, the submission policy, checking ethics, checking declarations like competing interests and funding requests. Then they organise the review, assist the editors to make a decision, do the copy editing and technical editing.

Alice used an animal analogy – the cheetah representing the speed of peer review that authors would like to see, but a tortoise represented what they experience. This was very interesting given the Nature news piece that was published on 10 February “Does it take too long to publish research?”

Will Frass is a Research Executive at Taylor & Francis and discussed the findings of a T&F study “Peer review in 2015 – A global view”. This is a substantial report and I won’t be able to do his talk justice here, there is some information about the report here, and a news report about it here.

One of the comments that struck me was that researchers in the sciences are generally more comfortable with single blind review than in the humanities. Will noted that because there are small niches in STM, double blind often becomes single blind anyway as they all know each other.

A question from the floor was that reviewers spend eight hours on a paper and their time is more important than publishers’. The question was asking what publishers can do to support peer review? While this was not really answered on the floor* it did cause a bit of a flurry on Twitter with a discussion about whether the time spent is indeed five hours or eight hours – quoting different studies.

*As a general observation, given that half of the participants at the conference were publishers, they were very underrepresented in the comment and discussion. This included the numerous times when a query or challenge was put out to the publishers in the room. As someone who works collaboratively and openly, this was somewhat frustrating.

The Sociology of Research

Professor James Evans, who is a sociologist looking at the science of science at the University of Chicago spoke about How research scientists actually behave as individuals and in groups.

His work focuses on the idea of using data from the publication process that tell rich stories into the process of science. James spoke about some recent research results relating to the reading and writing of science including peer reviews and the publication of science, research and rewarding science.

James compared the effect of writing styles to see what is effective in terms of reward (citations). He pitted ‘clarity’ – using few words and sentences, the present tense, and maintaining the message on point against ‘promotion’ – where the author claims novelty, uses superlatives and active words.

The research found writing with clarity is associated with fewer citations and writing in promotional style is associated with greater citations. So redundancy and length of clauses and mixed metaphors end up enhancing a paper’s search ability. This harks back to the conversation about poor academic writing the day before – bad writing is rewarded.

Scientists write to influence reviewers and editors in the process. Scientists strategically understand the class of people who will review their work and know they will be flattered when they see their own research. They use strategic citation practices.

James noted that even though peer review is the gold standard for evaluating the scientific record. In terms of determining the importance or significance of scientific works his research shows peer review is inconsistent and systematically biased. The greater the reviewer distance results in more positive reviews. This is possibly because if a person is reviewing work close to their speciality, they can see all the criticism. The greater the novelty of the work the greater likelihood it is to have a negative review. It is possible to ‘game’ this by driving the peer review panels. James expressed his dislike of the institution of suggesting reviewers. These provide more positive, influential and worse reviews (according to the editors).

Scientists understand the novelty bias so they downplay the new elements to the old elements. James discussed Thomas Kuhn’s concept of the ‘essential tension’ between the classes of ‘career considerations’ – which result in job security, publication, tenure (following the crowd) and ‘fame’ – which results in Nature papers, and hopefully a Nobel Prize.

This is a challenge because the optimal question for science becomes a problem for the optimal question for a scientific career. We are sacrificing pursuing a diffuse range of research areas for hubs of research areas because of the career issue.

The centre of the research cycle is publication rather than the ‘problems in the world’ that need addressing. Publications bear the seeds of discovery and represent how science as a system thinks. Data from the publication process can be used to tune, critique and reimagine that process.

James demonstrated his research that clearly shows that research today is driven by last year’s publications. Literally. The work takes a given paper and extracts the authors, the diseases, the chemicals etc and then uses a ‘random walk’ program. The result ends up predicting 95% of the combinations of authors and diseases and chemicals in the following year.

However scientists think they are getting their ideas, the actual origin is traceable in the literature. This means that research directions are not driven by global or local health needs for example.

Panel: Show me the Money

I sat on this panel discussion about ‘The financial implications of open access for researchers, intermediaries and readers’ which made it challenging to take notes (!) but two things that struck me in the discussions were:

Rick Andersen suggested that when people talk about ‘percentages’ in terms of research budgets they don’t want you to think about the absolute number, noting that 1% of Wellcome Trust research budget is $7 million and 1% of the NIH research budget is $350 million.

Toby Green, the Head of Publishing for the OECD put out a challenge to the publishers in the audience. He noted that airlines have split up the cost of travel into different components (you pay for food or luggage etc, or can choose not to), and suggested that publishers split APCs to pay for different aspects of the service they offer and allow people to choose different elements. The OECD has moved to a Freemium model where that the payment comes from a small number of premium users – that funds the free side.

As – rather depressingly – is common in these kinds of discussions, the general feeling was that open access is all about compliance and is too expensive. While I am on the record as saying that the way the UK is approaching open access is not financially sustainable, I do tire of the ‘open access is code for compliance’ conversation. This is one of the unexpected consequences of the current UK open access policy landscape. I was forced to yet again remind the group that open access is not about compliance, it is about providing public access to publicly funded research so people who are not in well resourced institutions can also see this research.

Research in Institutions

Graham Stone, the Information Resources Manager, University of Huddersfield talked about work he has done on the life cycle of open access for publishers, researchers and libraries. His slides are available.

Graham discussed how to get open access to work to our advantage, saying we need to get it embedded. OAWAL is trying to get librarians who have had nothing to do with OA into OA.

Graham talked the group through the UK Open Access Life Cycle which maps the research lifecycle for librarians and repository managers, research managers, fo authors (who think magic happens) and publishers.

My talk was titled ‘Getting an Octopus into a String Bag’. This discussed the complexity of communicating with the research community across a higher education institution. The slides are available.

The talk discussed the complex policy landscape, the tribal nature of the academic community, the complexity of the structure in Cambridge and then looked at some of the ways we are trying to reach out to our community.

While there was nothing really new from my perspective – it is well known in research management circles that communicating with the research community – as an independent and autonomous group – is challenging. This is of course further complicated by the structure of Cambridge. But in preliminary discussions about the conference, Mark Carden, the conference organiser, assured me that this would be news to the large number of publishers and others who are not in a higher education institution in the audience.

Summary: What does everybody want?

Mark Carden summarised the conference by talking about the different things different stakeholder in the publishing game want.

Researchers/Authors – mostly they want to be left alone to get on with their research. They want to get promoted and get tenure. They don’t want to follow rules.

Readers – want content to be free or cheap (or really expensive as long as something else is paying). Authors (who are readers) do care about the journals being cancelled if it is one they are published in. They want a nice clear easy interface because they are accessing research on different publisher’s webpages. They don’t think about ‘you get what you pay for.’

Institutions – don’t want to be in trouble with the regulators, want to look good in league tables, don’t want to get into arguments with faculty, don’t want to spend any money on this stuff.

Libraries – Hark back to the good old days. They wanted manageable journal subscriptions, wanted free stuff, expensive subscriptions that justified ERM. Now libraries are reaching out for new roles and asking should we be publishers, or taking over the Office of Research, or a repository or managing APCs?

Politicians – want free public access to publicly funded research. They love free stuff to give away (especially other people’s free stuff).

Funders – want to be confusing, want to be bossy or directive. They want to mandate the output medium and mandate copyright rules. They want possibly to become publishers. Mark noted there are some state controlled issues here.

Publishers – “want to give huge piles of cash to their shareholders and want to be evil” (a joke). Want to keep their business model – there is a conservatism in there. They like to be able to pay their staff. Publishers would like to realise their brand value, attract paying subscribers, and go on doing most of the things they do. They want to avoid Freemium. Publishers could be a platform or a mega journal. They should focus on articles and forget about issues and embrace continuous publishing. They need to manage versioning.

Reviewers – apparently want to do less copy editing, but this is a lot of what they do. Reviewers are conflicted. They want openness and anonymity, slick processes and flexibility, fast turnaround and lax timetables. Mark noted that while reviewers want credit or points or money or something, you would need to pay peer reviewers a lot for it to be worthwhile.

Conference organisers – want the debate to continue. They need publishers and suppliers to stay in business.

Rafael Carazo-Salas

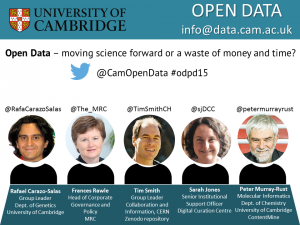

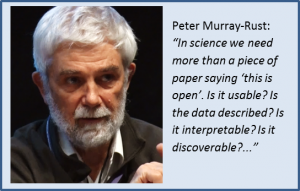

Rafael Carazo-Salas The discussion started off with a request for a definition of what “open” meant. Both Peter and Sarah explained that ‘open’ in science was not simply a piece of paper saying ‘this is open’. Peter said that ‘open’ meant free to use, free to re-use, and free to re-distribute without permission. Open data needs to be usable, it needs to be described, and to be interpretable. Finally, if data is not discoverable, it is of no use to anyone. Sarah added that sharing is about making data useful. Making it useful also involves the use of open formats, and implies describing the data. Context is necessary for the data to be of any value to others.

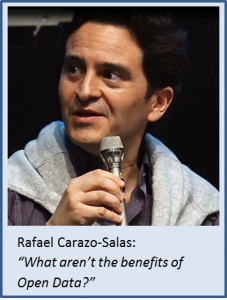

The discussion started off with a request for a definition of what “open” meant. Both Peter and Sarah explained that ‘open’ in science was not simply a piece of paper saying ‘this is open’. Peter said that ‘open’ meant free to use, free to re-use, and free to re-distribute without permission. Open data needs to be usable, it needs to be described, and to be interpretable. Finally, if data is not discoverable, it is of no use to anyone. Sarah added that sharing is about making data useful. Making it useful also involves the use of open formats, and implies describing the data. Context is necessary for the data to be of any value to others. Next came a quick question from Danny: “What are the benefits of Open Data”? followed by an immediate riposte from Rafael: “What aren’t the benefits of Open Data?”. Rafael explained that open data led to transparency in research, re-usability of data, benchmarking, integration, new discoveries and, most importantly, sharing data kept it alive. If data was not shared and instead simply kept on the computer’s hard drive, no one would remember it months after the initial publication. Sharing is the only way in which data can be used, cited, and built upon years after the publication. Frances added that research data originating from publicly funded research was funded by tax payers. Therefore, the value of research data should be maximised. Data sharing is important for research integrity and reproducibility and for ensuring better quality of science. Sarah said that the biggest benefit of sharing data was the wealth of re-uses of research data, which often could not be imagined at the time of creation.

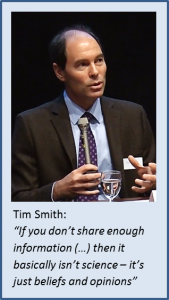

Next came a quick question from Danny: “What are the benefits of Open Data”? followed by an immediate riposte from Rafael: “What aren’t the benefits of Open Data?”. Rafael explained that open data led to transparency in research, re-usability of data, benchmarking, integration, new discoveries and, most importantly, sharing data kept it alive. If data was not shared and instead simply kept on the computer’s hard drive, no one would remember it months after the initial publication. Sharing is the only way in which data can be used, cited, and built upon years after the publication. Frances added that research data originating from publicly funded research was funded by tax payers. Therefore, the value of research data should be maximised. Data sharing is important for research integrity and reproducibility and for ensuring better quality of science. Sarah said that the biggest benefit of sharing data was the wealth of re-uses of research data, which often could not be imagined at the time of creation. Tim also stressed that if open science became institutionalised, and mandated through policies and rules, it would take a very long time before individual researchers would fully embrace it and start sharing their research as the default position.

Tim also stressed that if open science became institutionalised, and mandated through policies and rules, it would take a very long time before individual researchers would fully embrace it and start sharing their research as the default position. Frances mentioned that in the case of personal and sensitive data, sharing was not as simple as in basic sciences disciplines. Especially in medical research, it often required provision of controlled access to data. It was not only important who would get the data, but also what they would do with it. Frances agreed with Tim that perhaps what was needed is a paradigm shift – that questions should be sent to the data, and not the data sent to the questions.

Frances mentioned that in the case of personal and sensitive data, sharing was not as simple as in basic sciences disciplines. Especially in medical research, it often required provision of controlled access to data. It was not only important who would get the data, but also what they would do with it. Frances agreed with Tim that perhaps what was needed is a paradigm shift – that questions should be sent to the data, and not the data sent to the questions. Danny mentioned that the traditional way of rewarding researchers was based on publishing and on journal impact factors. She asked whether publishing data could help to start rewarding the process of generating data and making it available. Sarah suggested that rather than having the formal peer review of data, it would be better to have an evaluation structure based on the re-use of data – for example, valuing data which was downloadable, well-labelled, re-usable.

Danny mentioned that the traditional way of rewarding researchers was based on publishing and on journal impact factors. She asked whether publishing data could help to start rewarding the process of generating data and making it available. Sarah suggested that rather than having the formal peer review of data, it would be better to have an evaluation structure based on the re-use of data – for example, valuing data which was downloadable, well-labelled, re-usable. The final discussion was around incentives for data sharing. Sarah was the first one to suggest that the most persuasive incentive for data sharing is seeing the data being re-used and getting credit for it. She also stated that there was also an important role for funders and institutions to incentivise data sharing. If funders/institutions wished to mandate sharing, they also needed to reward it. Funders could do so when assessing grant proposals; institutions could do it when looking at academic promotions.

The final discussion was around incentives for data sharing. Sarah was the first one to suggest that the most persuasive incentive for data sharing is seeing the data being re-used and getting credit for it. She also stated that there was also an important role for funders and institutions to incentivise data sharing. If funders/institutions wished to mandate sharing, they also needed to reward it. Funders could do so when assessing grant proposals; institutions could do it when looking at academic promotions.