[NOTE: The introductory sentence to this blog was changed on 27 June to provide clarification]

Last week members of the University of California* released a Call to Action to ‘Champion change in journal negotiations’ which references the April 2018 Declaration of Rights and Principles to Transform Scholarly Communication. This states as one of the 18 principles:

“No free labor. Publishers shall provide our Institution with data on peer review and editorial contributions by our authors in support of journals, and such contributions shall be taken into account when determining the cost of our subscriptions or OA fees for our authors.”

Well, this is interesting. At Cambridge we have been trying to look at this specific issue since late last year.

The project

Our goal was to have a better understanding of the interaction between publisher and researcher. The (not very imaginatively named) Data Gathering Project is a project to support the decision making of the Journal Coordination Scheme in relation to subscription to, and use of, academic journal literature across Cambridge.

What we have initially found is that the data is remarkably difficult to put together. Cambridge University does not use bibliometrics as a means of measuring our researchers, so we do not subscribe to SciVal, but we have access to Scopus. But Scopus does not pick up Arts and Humanities publications particularly well, so it will always be a subset of the whole.

Some information that we thought would be helpful simply isn’t. We do have an institutional Altmetric account, so we were able to pull a report from Altmetric of every paper with a Cambridge author held in that database. But Altmetric does not give a publisher view – we would have to extract this using doi prefixes or some other system.

Cambridge uses Symplectic Elements to record publications from which, for very complicated reasons, we are unable to obtain a list of publishers with whom we publish. As part of the subscription we have access to the new analysing product, Dimensions. However, as far as we have managed to see, Dimensions does not break down by publisher (it works at the more granular level of journal), and seems to consider anything that is in the open domain (regardless of licence) to be ‘open access’. So figures generated here come with a heavy caveat.

We are also able to access the COUNTER usage statistics for our journals with the help of the Library eresources team. However these include downloads for backfiles and for open access articles, so the numbers are slightly inflated, making a ‘cost per download’ analysis of value against subscription cost inaccurate.

We know how much we spend on subscriptions (spoiler alert: a lot). We need to take into consideration our offsetting arrangements with some publishers – something we are taking an active look at currently anyway.

Reaching out to the publishing community

So to supplement the aggregated information we have to hand, we have reached out to those publishers our researchers publish with in significant quantities to ask them for the following data on Cambridge authors: Peer Reviewing, Publishing, Citing, Editing, and Downloading.

This is exactly what the University of California is demanding. One of the reasons we need to ask publishers for peer review information is because it is basically hidden work. Aggregating systems like Publons do help a bit, although the Cambridge count of reviewers in the system is only 492 which is only a small percentage of the whole. Publons was bought out by Clarivate Analytics (which was Thompson Reuters before this and ISI before that) a year ago. We did approach Clarivate Analytics for some data about our peer reviewing, but declined to pay the eye watering quoted fee.

What have we received?

Contrary to our assumptions, many of the publishers responded saying that this information is difficult to compile because it is held on different systems and that multiple people would need to be contacted. Sometimes this is because publishers are responsible for the publication of learned society journals so information is not stored centrally. They also fed back that much of the data is not readily available in a digestible format.

Some publishers have responded with data on Cambridge peer reviewers and editors, usage statistics, and citation information. A big thank you to Emerald, SAGE, Wiley, the Royal Society and eLife. We are in active correspondence with Hindawi and PLOS. [STOP PRESS: SpringerNature provided their data 30 minutes after this blog went live, so thanks to them as well].

However, a number of publishers have not responded to our requests and one in particular would like to have a meeting with us before releasing any information.

Findings so far

The brief for the project was to ‘understand how our researchers interact with the literature’. While we wrote the brief ourselves, we have come to realise it is actually very vague. We have tried to gather any data we can to start answering this question.

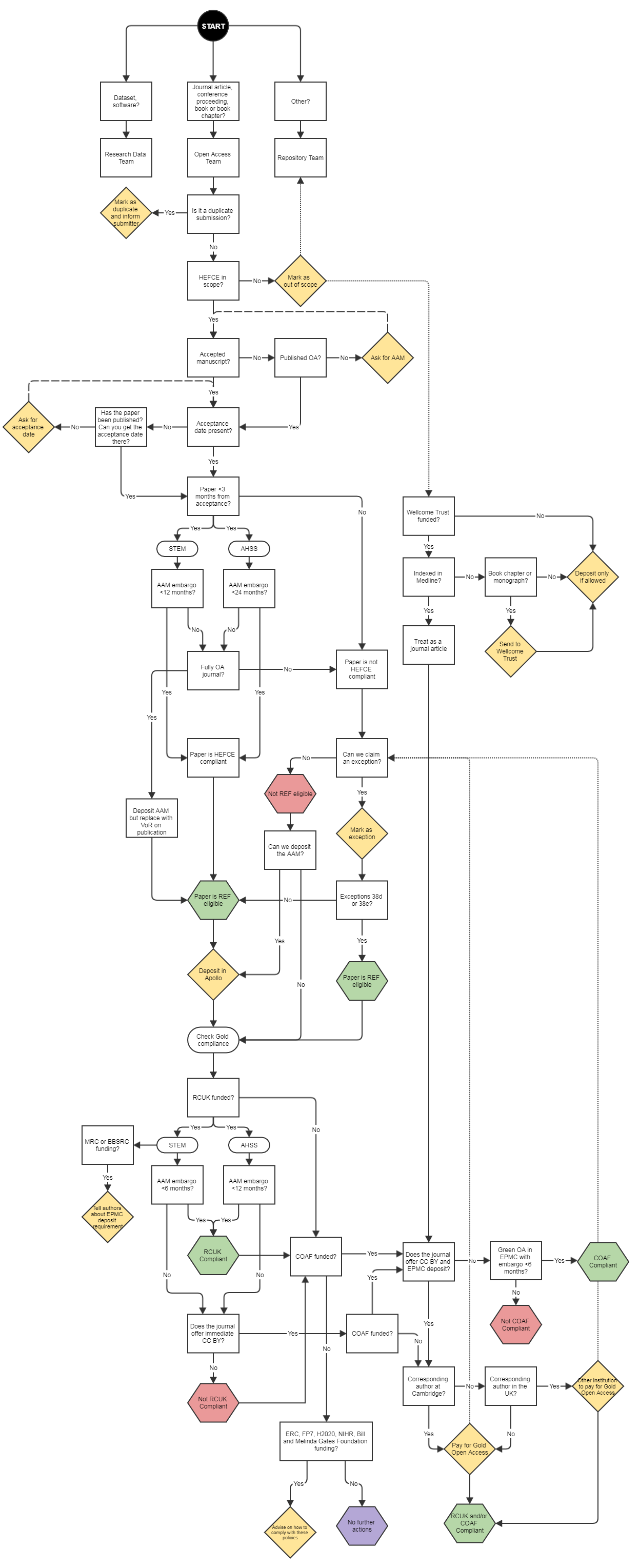

What the data we have so far is helping us understand is how much is being spent on APCs outside the central management of the Office of Scholarly Communication (OSC). The OSC manages the block grants from the RCUK (now UKRI) and the Charities Open Access Fund, but does not look after payments for open access for research funded by, say the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation or the NIH. This means that there is a not insignificant amount of extra expenditure on top of that coordinated by the OSC. These amounts are extremely difficult to ascertain as observed in 2014.

We already collect and report on how much the Office of Scholarly Communication has spent on APCs since 2013. However some prepayment deals makes the data difficult to analyse because of the way the information is presented to us. For example, Cambridge began using the Wiley Dashboard in the middle of the year with the first claim against it on 6 July 2016, so information after that date is fuzzy.

The other issue with comparing how much a publisher has received in APCs and how much the OSC has paid (to determine the difference) is dates. We have already talked at length about date problems in this space. But here the issue is publisher provided numbers are based on calendar years. Our reporting years differ – RCUK reports from April to March and COAF from October to September, so pulling this information together is difficult.

Our current approach to understanding the complete expenditure on APCs, apart from analysing the data being provided by (some) publishers, is to establish all of the suppliers to whom the OSC has paid an APC and obtain the supplier number. This list of supplier numbers can then be run against the whole University to identify payments outside the OSC.

This project is far from straightforward. Every dataset we have will require some enhancement. We have published a short sister post on what we have learned so far about organising data for analysis. But we are hoping over the next couple of months to start getting a much clearer idea of what Cambridge is contributing into the system – in terms of papers, peer review and editorial work in addition to our subscriptions and APCs. We need more evidence based decision making for negotiation.

Footnote

* There has been some discussion in listservs about who is behind the Call to Action and the Declaration. Thanks to Jeff MacKie-Mason, University Librarian and Professor, School of Information and Professor of Economics at UC Berkeley, we are happy to clarify:

- The Declaration is by the faculty senate’s library committee – University Committee on Library and Scholarly Communication (UCOLASC)

- The Call to Action is by the University of California’s Systemwide Library and Scholarly Information Advisory Committee, UCOLASC, and the UC Council of University Librarians, who: “seek to engage the entire UC academic community, and indeed all stakeholders in the scholarly communication enterprise, in this journey of transformation”.

Published 26 June 2018 (amended 27 June 2018)

Written by Dr Danny Kingsley & Katie Hughes