For the past four years at the end of February, publishers, librarians, agents, researchers, technologists and consultants have gathered in London for two days of discussions around the concept of ‘Researcher to Reader’. This blog is my take on what I found the most inspiring, challenging and interesting at the 2019 event. There wasn’t a theme this year per se, but something that did repeatedly arise from where I was standing was the diversity of our perspectives. This is a word that has taken a specific meaning recently, so I am using ‘multiplicity’ instead :

- The principles of Plan S are calling for multiple business models for open access publishing, according to Dr Mark Schiltz

- There is now great range in the approaches researchers take to the writing process, as described by Dr Christine Tulley

- Professor Siva Umpathy described the disparity of standards of living in India which has a profound effect on whether students can engage with research regardless of talent

- In order to ensure reproducibility of research, we need multiplicity in the research landscape with larger number of smaller research groups working on a wide array of questions, argued Professor James Evans

- Cambridge University Press is trying to break away from the Book/Journal dichotomy, diversifying with a long-form publication called Cambridge Elements

- SpringerNature and Elsevier are expanding their business models to encroach into data management and training (although the analogy starts to fall apart here – what this actually represents is a concentration of the market overall).

Anyway, that gives you an idea of the kinds of issues covered. The conference programme is available online and you can read the Twitter conversation from the event (#R2Rconf). Read on for more detail.

The 2019 meeting was, once again, a great programme. (I say that as a member of the Advisory Board, I admit, but it really was).

The Plan S-shaped elephant in the room

Both days began with a bang. The meeting opened with a keynote from Dr Mark Schiltz – President at Science Europe and Secretary General & Executive Head at the Luxembourg National Research Fund – talking about “Plan S and European Research”.

Schiltz explained he felt the current publishing system is a barrier to ensuring the outcomes of research are freely available, noting that hiding results is the antithesis of the essence of science. There was a ‘duty of care’ for funders to invest public funds well to support research. He suggested that there has been little progress in increasing open access to publications since 2009. In terms of the mechanisms of Plan S, he emphasised there are many compliant routes to publication and Plan S “is not about gold OA as the only publication model, it is about principles”. He also noted that there are plans to align Plan S principles with those of OA2020.

Schiltz explained he felt the current publishing system is a barrier to ensuring the outcomes of research are freely available, noting that hiding results is the antithesis of the essence of science. There was a ‘duty of care’ for funders to invest public funds well to support research. He suggested that there has been little progress in increasing open access to publications since 2009. In terms of the mechanisms of Plan S, he emphasised there are many compliant routes to publication and Plan S “is not about gold OA as the only publication model, it is about principles”. He also noted that there are plans to align Plan S principles with those of OA2020.

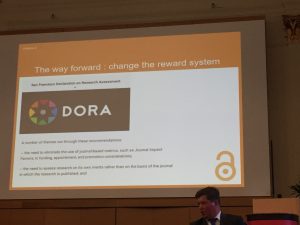

As is mentioned in the Plan S principles. Schiltz ended by arguing for the need to revise the incentivisation system in scholarly communications through mechanisms such as DORA. This is the “next big project” for funders, he said.

As is mentioned in the Plan S principles. Schiltz ended by arguing for the need to revise the incentivisation system in scholarly communications through mechanisms such as DORA. This is the “next big project” for funders, he said.

Catriona McCallum from Hindawi noted DORA is the most vital component for Plan S to work and therefore we need a proper roadmap. She asked if there was a timeline for how funders will make changes to their own systems for evaluating research and grant applications, as this is an area where societies and funders should work together. Schiltz responded that this process is about making concrete changes to practice, not just policy. There is no timeline but there has been more attention on this than ever before. He noted that Dutch universities are meeting next year to redefine tenure/promotion standards which will be interesting to follow. McCallum observed it could take decades if there is no timeline upfront.

One of the early questions from the audience was from a publisher asking why mirror journals were not permitted under Plan S because they are not hybrid journals. Schiltz disagreed, saying if the journals have the same editorial board then it is effectively hybrid because readers will still need to subscribe to the other half, as they would for hybrid. Needless to say, the publisher disagreed.

The question about why Plan S architects didn’t consult with learned societies before going public was not particularly well answered. Schiltz talked about the numbers of hybrid journals being greater than pure subscription journals now and there was concern that hybrid becomes dominant business model. He said we need an actual transition to gold OA, which is all very well but doesn’t actually answer the question. He did note that: “We do not want learned societies to become collateral damage of Plan S”. He acknowledged that many learned societies use surpluses from their publishing businesses to fund good work. But he did ask: “Is the use of thinly spread library budget to subsidise learned societies’ philanthropic activities appropriate, and to what degree? This is not sustainable”.

So, how do researchers approach the writing process?

Professor Christine Tulley, Professor of English at the University of Findlay, Ohio spoke about “How Faculty Write for Publication, Examining the academic lifecycle of faculty research using interview and survey data”. Tulley is involved with training researchers in writing and publishing among other roles. She has published a book called How Writing Faculty Write, Strategies for Process, Product and Productivity based on her research with top researchers who research about writing. She is also collaborating on De Gruyter survey of researchers on writing (with whom she co-facilitated a workshop on this topic, discussed later in this blog).

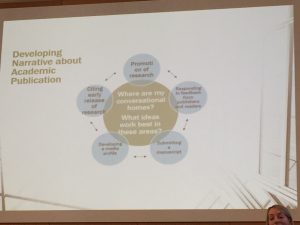

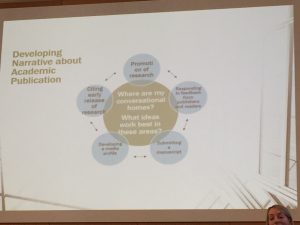

Tulley’s first observation is that academics think ‘rhetorically’. Regardless of discipline, her findings in the US show that thinking about where you want publish and the community you want to reach is more important to academics than coming up with an idea. Tulley noted that in the past, the process was that academics wrote first then decided where to publish. But this is not the case now, where instead authors consider readership in the first instance, asking themselves what is the best medium to reach that audience. This is a focus on what can be a narrow audience that an author wants to hit – it is not a matter of ‘reach the world’ but can be as few as five important people. This can limit end publication options.

Tulley’s first observation is that academics think ‘rhetorically’. Regardless of discipline, her findings in the US show that thinking about where you want publish and the community you want to reach is more important to academics than coming up with an idea. Tulley noted that in the past, the process was that academics wrote first then decided where to publish. But this is not the case now, where instead authors consider readership in the first instance, asking themselves what is the best medium to reach that audience. This is a focus on what can be a narrow audience that an author wants to hit – it is not a matter of ‘reach the world’ but can be as few as five important people. This can limit end publication options.

She also observed that after the top two or three journals, then their rank matters less. Because of this, newer journals/ open access publications can attract readers and submissions, particularly through early release, which is more important that ‘official publication’ she observed. This does talk to the recent increase in general interest in preprints.

In a statement that set the hearts of the librarians in the audience aflutter, Tulley spoke about librarians as “tip-off providers”, being especially useful for early online release of research before the indexing kicks in. She noted that academics view librarians as scholarly research ‘Partners’ rather than ‘Support’. We have also had this discussion within the UK library community.

Equity of access to education

It is always really interesting to hear perspectives from elsewhere – be that across the library/researcher/publisher divides, or across global ones. Two talks at the event were very interesting as they described the situation in India and Bangladesh, highlighting how some issues are shared worldwide and others are truly unique.

Prof Siva Umpathy, Director of the Indian Institute of Science Education, Bhopal, spoke first, emphasising that he was giving his personal opinion, not that of the Indian government. He noted that taxpayers pay for higher education in India and this is the case for most of the global south – fees to students are much less common. This means education is seen as a social responsibility of government.

Umpathy noted that 40% of the population in India is currently under 35 years old. infrastructure and opportunities vary significantly within India let alone across the whole ‘global south’. In some areas of India, the standard of living is equivalent to London. In other areas there is no internet connection. This affects who can engage with research, some very bright students from small villages are at a disadvantage. Even the kind of information that might be available to students in India about where to study and how to apply can be uneven affecting ambitions regardless of how talented the student might be. He described the incredibly competitive process to gain a place in a university, consisting of applications, exams and interviews.

In India, when someone is paying to publish a paper it gives an impression that the work is not as high a quality, after all, if you have good science you shouldn’t have to pay for publication. I should note this is not unique to India – witness an article that was published in The Times Literary Supplement the day after this talk that entirely confuses what open access monograph publishing is about (“Vain publishing – The restrictions of ‘open access’”).

Beyond impressions there are practical issues – bureaucrats don’t understand why an academic would pay for open access publication, why they wouldn’t publish in the ‘best’ mainstream journals, therefore funding in India does not allow for any payment for publishing. This is despite India being a big consumer of open access research. This has practical implications. If India were to join Plan S and mandated OA, it will likely reduce the number of papers he is able to publish by half, because there’s no government funding available to cover APCs.

He called for the need to train and editors and peer reviewers and the importance of educating governments, funders and evaluators and suggested that peer-reviewers are given APC discounts to encourage them to review more for journals. This, of course is an issue in the Global North too. Indeed when we ran some workshops on Peer Review late last year. They were doubly subscribed immediately.

Global reading, local publishing – Bangladesh

Dr Haseeb Irfanullah, a self described ‘research communications enthusiast’ spoke about what Bangladesh can tell us about research communications. He began by noting how access to scientific publications has been improved by the Research 4 Life Partnership and INASP. These innovations for increasing access to research literature to global south over past few years have been a ‘revolution’. He also discussed how the Bangladesh Journals Online project has helped get Bangladeshi journals online, including his journal, Bangladesh Journal of Plant Taxonomy. This helps journals get journal impact factors (JIF).

However, Bangladesh journal publishing is relatively isolated, and is ‘self sustaining’. Locally sourced content fulfils the need. Because promotion, increments and recognition needs are met with the current situation (universities don’t require indexed journals for promotion), then this means there is little incentive to change or improve the process. This seems to be example of how a local journal culture can thrive when researchers are subject to different incentives, although perversely the downside is that they & their research are isolated from international research. A Twitter observation about the JIF was “damned if you do or damned if you don’t”.

However, Bangladesh journal publishing is relatively isolated, and is ‘self sustaining’. Locally sourced content fulfils the need. Because promotion, increments and recognition needs are met with the current situation (universities don’t require indexed journals for promotion), then this means there is little incentive to change or improve the process. This seems to be example of how a local journal culture can thrive when researchers are subject to different incentives, although perversely the downside is that they & their research are isolated from international research. A Twitter observation about the JIF was “damned if you do or damned if you don’t”.

He also noted that it is ‘very cheap to publish a journal as everyone is a volunteer’, prompting one person on Twitter to ask: “Is it just me or is this the #elephantintheroom we need to address globally?” Irfanullah has been involved in providing training for editors, workshops and dialogues on standards, mentorship to help researchers get their work published, as well as improving access to research in Bangladesh. He concluded that these challenges can be addressed; for example, through dialogue with policymakers and a national system for standards.

Big is not best when it comes to reproducibility

Professor James Evans, from the Department of Sociology at Chicago University (who was a guest of Researcher to Reader in 2016) spoke on why centralised “big science” communities are more likely to generate non-replicable results by describing the differences between small and large teams. His talk was a whirlwind of slides (often containing a dizzy array of graphics) at breath-taking speed.

The research Evans and his team undertake looks at large numbers of papers to determine patterns that identify replicability and whether the increase in the size of research teams and the rise of meta research has any impact. For those interested, published papers include “Centralized “big science” communities more likely generate non-replicable results” and “Large Teams Have Developed Science and Technology; Small Teams Have Disrupted It”.

Evans described some of the consequences when a single mistake is reused and appears in multiple subsequent papers, ‘contaminating’ them. He used an example of the HeLa cell* in relation to drug gene interactions. Misidentified cells resulted in ‘indirect contamination’ of the 32,755 articles based on them, plus the estimated half a million other papers which cited these cells. This can represent a huge cost where millions of dollars’ worth of research has been contaminated by a mistake.

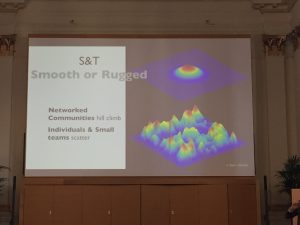

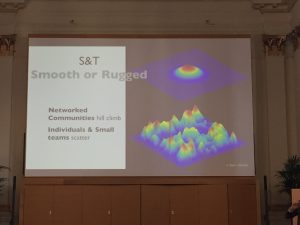

The problem is scientific communities use the same techniques and methods, which reduces the robust nature of research. Increasingly overlapping research networks with exposure to similar methodologies and prior knowledge – research claims are not being independently replicated. Claims that are highly centralised on star scientists, repeat collaborations & overlapping methods are far less robust and lead to huge distortion in the literature. the larger the team, the more likely their output will support and amplify rather than disrupt prior work. if there is an overlap, e.g. between authors or methodologies, there is more likely to be agreement.

Making the analogy of the difference between Slumdog Millionaire vs Marvel movies, Evans noted that independent, decentralised, non-overlapping claims are far more likely to be robust, replicable & of more benefit to society. It is effectively a form of triangulation. Smaller, decentralised communities are more likely to conduct independent experiments to reproduce results, producing more robust results. Small teams reach further into the past and looks to more obscure and independent work. Bigger is not better – smaller teams are more productive, innovative & disruptive because they have more to gain & less to lose than larger teams.

Large overlapping teams increase agglomeration around the same topics. The research landscape is seeing a decrease in small teams, and therefore a decrease in independence. These types of group receive less funding & are ‘more risky’ because they are not part of the centralised network.

Evans described a disruption to the scientific narrative building on what has incrementally happened before is effectively Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions from the 1960s. But “disruption delays impact” – there is a tendency of research teams to keep building on previous successes (which come with an existing audience) rather than risking disruption and consequent need for new audiences etc. In addition, the size of the team matters, one of their findings has been that each additional person on a team reduces the likelihood of research being disruptive. But disruption requires different funding models -with a taste for risk.

Evans noted that you need small teams simultaneously climbing different hills to find the best solution, rather than everyone trying to climb the same hill. This analogy was picked up by Catriona MacCallum who noted that publishers are actually all on the big hill which means they are in the same boat and trying to achieve the same end goal (hence the mess we are now in). So how do publishers move across to the disruptive landscape with lots of higher hills?

*The HeLa cell is an immortal cell line used in scientific research. It is the oldest and most commonly used human cell line. It is called HeLa because it came from a woman called Henrietta Lacks.

Sci Hub – harm or good?

The second day opened with a debate about Sci Hub on the question of “Is Sci-Hub is doing more good than harm to scholarly communication?”.

The audience was asked to vote whether they ‘agreed’ or ‘disagreed’ with the statement. In this first vote 60% of the audience disagreed and 40% agreed. Note this could possibly reflect attendance at the conference of publishers as the largest cohort of 51% of the attendees, or alternatively be a reflection of the slightly problematic wording of the question. More than one person observed on Twitter that they would have appreciated a ‘don’t know’ or ‘neither good nor bad’ options.

The debate itself was held between Dr Daniel Himmelstein, Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Pennsylvania (in the affirmative – that SciHub is doing good) and Justin Spence, Partner and Co-Founder at Publisher Solutions International (in the negative – that SciHub is doing harm). I have it on good authority the debate will be written up separately, so won’t do so here. One observation I noted was – the question did not define to whom or what the ‘harm’ was being done. The argument against appeared focused on harm to the market but the argument for was discussing benefit to society.

The discussion was opened up to the room but the comment that elicited a clap from the audience was from Jennifer Smith at St George’s University in London who asked if Elsevier’s profits are defensible when there are people on fun runs raising money for charities who are not anticipating their fundraising cash is going to publisher shareholders rather than supporting research. The question she asked is: “who is stealing from whom?”.

At the end of the debate the audience was asked to vote again at which point, 55% disagreed and 45% agreed meaning Himmelstein won over 5% of the audience. This seems surprising given that it seems very rare to actually change anyone’s mind.

But is it a book or a journal?

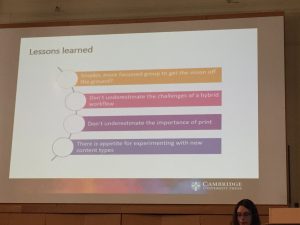

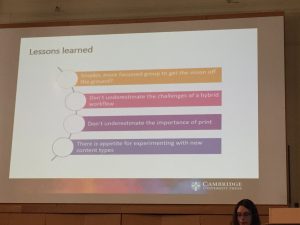

Nisha Doshi spoke about Cambridge Elements – a publication format that straddles the Book and Journal formats. It was interesting to hear about some of the challenges Cambridge University Press has faced. These ranged from practical in terms of which systems to use for production which seem to be very clearly delineated as either journal system or book systems. CUP is using several book systems, plus ISBNs, but also using ScholarOne for peer review for this project. Other issues have been philosophical. Authors and many others continue to ask “is it a journal or a book?”. CUP have encouraged authors to embed audio and video in their Cambridge Elements, but are not seeing much take-up so far which is interesting given the success of Open Book Publishers.

Doshi listed the lessons CUP has learned through the process of trying to get this new publication form off the ground. It was interesting to see how far Cambridge Elements has come. In October 2017 as part of our Open Access Week events, the OSC hosted CUP to talk about what was described at this point as their “hybrid books and journals initiative“.

Doshi listed the lessons CUP has learned through the process of trying to get this new publication form off the ground. It was interesting to see how far Cambridge Elements has come. In October 2017 as part of our Open Access Week events, the OSC hosted CUP to talk about what was described at this point as their “hybrid books and journals initiative“.

What’s the time Mr Wolf?

In 2016, Sally Rumsey and I spoke to the library communities at our institutions (Oxford and Cambridge, respectively) with a presentation: “Watch out, it’s behind you: publishers’ tactics and the challenge they pose for librarians”. Our warnings have increasingly been supported with publisher activity in the sector over the past three years. Two presentations at Researcher to Reader were along these lines.

In the first instance, Springer Nature presented on their Data Support Services which are a commercial offering in direct competition to the services offered by Scholarly Communication departments in libraries. I should note here that Elsevier also charge for a similar service through their Mendeley Data platform for institutions.

Representing an even further encroachment, the second presentation by Jean Shipman from Elsevier was about a new initiative which is training librarians to train researchers about data management. The new Elsevier Research Data Management Librarian Academy (RDMLA) has an emphasis on peer to peer teaching. Elsevier developed a needs assessment for RDM training, assessed library competencies, and library education curriculum before developing the RDMLA curriculum for RDM training. Example units include research data culture, marketing the program to administrators, and an overview of tools such as for coding. Elsevier moving into the training/teaching space is not new, they have had the ‘Elsevier Publishing Campus’ and ‘Researcher Academy’ for some time. But those are aimed at the research community. This new initiative is formally stepping directly into the library space.

Empathy mapping as a workshop structure

One of the features of Researcher to Reader is the workshops which are run in several sessions over the two day period. In all there is not much more time available than a traditional 2.5 – 3 hour workshop prior to the main event, but this format means there is more reflection time between sessions and does focus the thinking when you are all together.

I attended a workshop on “Supporting Early-Career Scholarship” asking: How can librarians, technologists and publishers better support early career scholars as they write and publish their work?

I attended a workshop on “Supporting Early-Career Scholarship” asking: How can librarians, technologists and publishers better support early career scholars as they write and publish their work?

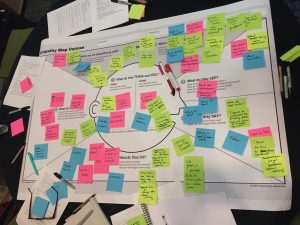

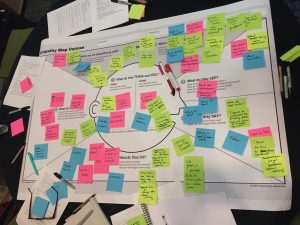

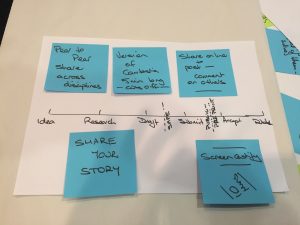

Ably facilitated by Bec Evans, Founder at Prolifiko with Dee Watchorn, Product Engagement Manager at De Gruyter and Christine Tulley, the workshop used a process called Empathy Mapping. Participants were given handouts with comments made by early career researchers during interviews about the writing process as part of a research programme by Prolifiko. This helped us map out the experience of ECRs from their perspective rather than guessing and imposing our own biases.

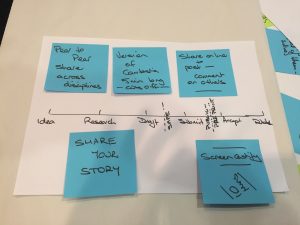

We were asked to come up with a problem – for my group it was “How can we help an ECR disseminate their first paper beyond the publication process?” And we were then asked to find a solution. Our group identified that these people need to understand the narrative of their work that they can then take through blogs, presentations, Twitter and other outlets. Our proposal was to create an online programme that only allowed 5 minutes for recording (in the way Screencastify only allows 10 minutes) an understandable explanation of their research that they can then upload for commentary by peers in a safe space before going public.

We were asked to come up with a problem – for my group it was “How can we help an ECR disseminate their first paper beyond the publication process?” And we were then asked to find a solution. Our group identified that these people need to understand the narrative of their work that they can then take through blogs, presentations, Twitter and other outlets. Our proposal was to create an online programme that only allowed 5 minutes for recording (in the way Screencastify only allows 10 minutes) an understandable explanation of their research that they can then upload for commentary by peers in a safe space before going public.

And so, to end

It is helpful to have different players together in a room. This is really the only way we can start to understand one another. As an indicator of where we are at, we cannot even agree on a common language for what we do – in a Twitter discussion about how SciHub is meeting an ‘ease of access’ need that has not been met by publishers or libraries, it became clear that while in the library space we talk about the scholarly publishing *ecosystem*, publishers consider libraries to be part of the scholarly publishing *industry*.

One tweet from a publisher was: “Good to hear Christine Tulley talk about why academics write and what it is important to them at #R2RConf . We don’t want to, but publishers too often think generically about authors as they do about content”. While slightly confronting (authors are not only their clients, but also provide the content for *free*, so should perhaps be treated with some respect), it does underline why it is so essential that we get researchers, librarians and publishers into the same room to understand one other better.

All the more reason to attend Researcher to Reader 2020!

Published 4 March 2019

Written by Dr Danny Kingsley