In October last year we reported on the first four months of our Request a Copy service. Now, 15 months in, we have had over 3000 requests and this provides us with a rich source of information to mine about the users of our repository. The dataset underpinning the findings described here is available in the repository.

What are people requesting?

We have had 3240 requests through the system since its inception in June 2016. Of those the vast majority have been for articles 1878 (58%) and theses 1276 (39%). The remaining requests are for book chapters, conference objects, datasets, images and manuscripts. It should be noted that most datasets are available open access which means there is little need for them to be requested.

Of the 23 requests for book chapters, it is perhaps not surprising that the greatest number – 9 (39%) came for chapters held in the collections from the School of Humanities and Social Sciences. It is however possibly interesting that the second highest number – 7 (30%) came for chapters held in the School of Technology.

The School of Technology is home to the Department of Engineering which is the University’s largest department. To that end it is perhaps not surprising that the greatest number of articles requested were from Engineering with 311 of the 1878 requests (17%) from here. The areas with next most requested number of articles were, in order, the Department for Public Health and Primary Care, the Department of Psychiatry, the Faculty of Law and the Judge Business School.

What’s hot?

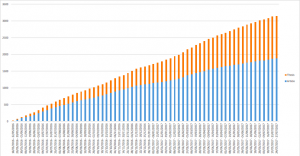

Over this period we have seen a proportional increase in the number of requests for theses compared to articles. When the service started the requests for articles were 71% versus 29% for theses. However more recently, theses have overtaken request for articles to a ratio of 54% to 46%.

Over this period we have seen a proportional increase in the number of requests for theses compared to articles. When the service started the requests for articles were 71% versus 29% for theses. However more recently, theses have overtaken request for articles to a ratio of 54% to 46%.

The most requested thesis, by a considerable amount, over this period was for Professor Stephen Hawking’s thesis with double the number of requests of the following ten most requested theses. The remaining top 10 requested theses are heavily engineering focused, with a nod to history and social research. These theses were:

- Calculation of Unbalanced Magnetic Pull in Cage Induction Machines

- Developing a comprehensive technology selection framework for practical application

- Young British readers’ engagement with manga

- Imperial succession in Tang China, 618-762

- Aerodynamics and mechanics of shuttlecocks

- Discourse processing during simultaneous interpreting: an expertise approach

- Highly loaded compressors

- Effects of tunnelling on buried pipes

- Angles of friction of granular fills

- Dynamics of bubbles, drops, and particles in motion in liquids

The top 10 requested articles have a distinctly health and behavioural focus, with the exception of one legal paper authored by Cambridge University’s Pro Vice Chancellor for Education, Professor Graham Virgo.

- Month of Conception and Learning Disabilities: A Record-Linkage Study of 801,592 Children

- Sugar Addiction: The State of the Science

- Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers

- Antidepressant activity of anti-cytokine treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials of chronic inflammatory conditions

- Patel v Mizra: one step forward and two steps back

- Environmental-mechanistic modelling of the impact of global change on human zoonotic 2 disease emergence: A case study of Lassa fever

- A decade into Facebook: where is psychiatry in the digital age?

- Human influences on evolution, and the ecological and societal consequences

- Childhood gender-typed behavior and adolescent sexual orientation: A longitudinal population-based study

- Effects of Saturated Fat, Polyunsaturated Fat, Monounsaturated Fat, and Carbohydrate on Glucose-Insulin Homeostasis: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Feeding Trials

When are people requesting?

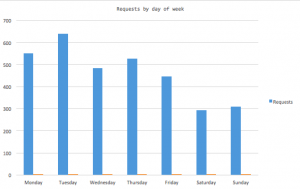

Looking at the day of the week people are requesting items, there is a distinct preference for early in the week. This reflects the observations we have made about the use of our helpdesk and deposits to our service – both of which are heaviest on Tuesdays.

Looking at the day of the week people are requesting items, there is a distinct preference for early in the week. This reflects the observations we have made about the use of our helpdesk and deposits to our service – both of which are heaviest on Tuesdays.

When in the publication cycle are the requests happening?

In our October 2016 blog we noted that of the articles requested in the four months from when the service started in June 2016 to the end of September 2016, 45% were yet to be published, and 55% were published but not yet available to those without a subscription to the journal. The method we used for working this out involved identifying those articles which had been requested and determining if the publication date was after the request.

Now, 15 months after the service began it is slightly more difficult to establish this number. We can identify items that were deposited on acceptance because we place these items on a very long embargo (until 2100) until we can establish the publication date and set the embargo period. So in theory we could compare the number of articles with this embargo period against those that have a different date.

However articles that would provide a false positive (that appear to have been requested before publication) would be ones which had been published but we had not yet identified this – to give an indication of how big an issue this is for us, as of the end of last week there were 1768 articles in our ‘to be checked’ pile. We would also have articles that would provide a false negative (that appear to have been requested after publication) because they had been published between the request and the time of the report and the embargo had been changed as a result. That said, after some analysis of the requests for articles and conference proceedings, 19% are before publication. This is a slightly fuzzy number but does give an indication.

How many requests are fulfilled?

The vast majority of the decisions recorded (35% of the total requests for articles, but 92% of the instances where we had a decision) indicate that the requestor shared their article with the requestor. The small number (3%) of ‘no’ recordings we have indicate the request was actively rejected.

We do not have a decision recorded from the author in 62% of the requests. We suspect that in the majority of these the request simply expires from the author not doing anything. In some cases the author may have been in direct correspondence with the requestor. We note that the email that is sent to authors does look like spam. In our review of this service we need to address this issue.

Next steps

As we explained in October, the process for managing the requests is still manual. As the volume of requests is increasing the time taken is becoming problematic. We estimate it is the equivalent of 1 person day per week. We are scoping the technical requirements for automating these processes. A new requirement at Cambridge for the deposit of digital theses means there will be three different processes because requests for these theses will be sent to the author for their decision. These authors will, in most cases, no longer be affiliated with Cambridge. Requests for digitised theses where we do not have the author’s permission are processed within the Library and requests for articles are sent to the Cambridge authors.

Given the challenges with identifying when in the publication process the request has been made, we need to look at automating the system in a manner that allows us to clearly extract this information. The percentage of requests that occur before publication is a telling number because it indicates the value or otherwise of having a policy of collecting articles at the acceptance point rather than at publication.