As the nights draw in and the academic year 2018/19 begins, we are preparing to enter our second year of compulsory e-theses deposits. Our university repository, Apollo, is close to holding 6000 digital PhD theses and it is the intention of the University that this valuable research asset continues to grow into the future. The Apollo repository will play a large part in making this happen. Until recently only hardbound copies of theses were collected and catalogued by the University Library. Users could read theses on-site in Cambridge or order a digitisation of the thesis, but the introduction of e-thesis deposit to Apollo has meant that University of Cambridge theses are more accessible than ever before. It’s been an incredibly busy year and we have made some great steps forward in our management of theses in Cambridge.

e-theses at Cambridge – the background

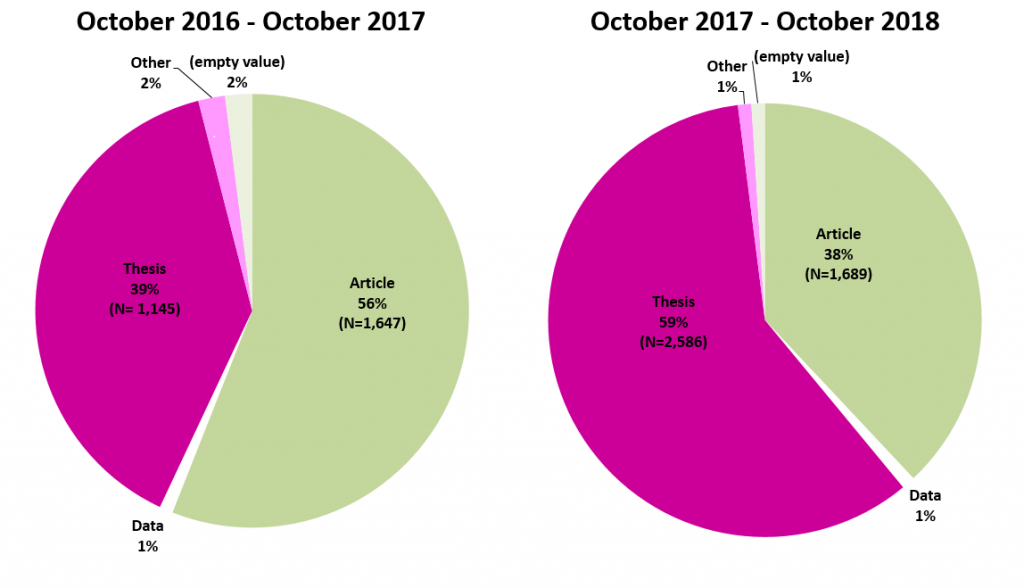

The e-theses deposit story at Cambridge started in October 2016, when the Office of Scholarly Communication upgraded Apollo to allow the deposit of theses and began a digital thesis pilot for the academic year 2016/17. 11 departments in the University participated in the pilot, asking their PhD students to deposit an e-thesis alongside a hardcopy thesis. Theses deposited in Apollo during the pilot could either be made open access on request of the author or were treated as historical theses had been up until that point, whereby hardbound copies were held in the University Library and requestors could sign a declaration stating they wish to consult a thesis for private study or non-commercial research. Following the success of the pilot, the Board of Graduate Studies, at its meeting on 4 July 2017, made the decision that from 1 October 2017 all PhD students would be required to deposit both a hard copy and an electronic copy of their thesis to the University Library.

What we learnt during the academic year 2017/18

The experience of depositing theses during the pilot had highlighted some issues that needed addressing. We had to make decisions on how to deal with third party copyright, sensitive material, library copy and supply rules, and the alignment of access levels for hardbound and electronic theses. In response to this, we decided that we should think through each of the different ways in which a thesis could be deposited in the repository, and consider the range of contentious material that could be contained within a thesis.

How do theses enter the repository?

Whilst students that are depositing in order to graduate do this directly, we also have the capacity to scan theses on request here in the library, and these scanned theses are subsequently deposited in Apollo. In addition to this, we led a drive to digitise University of Cambridge theses held by the British Library on microfilm and gave alumni the option to digitise their thesis and make it open access at no cost to them.

British Library theses

This year the OSC has made a bulk deposit of theses scanned by the British Library, which significantly augments the number of theses stored in the repository. In the culmination of a two-year project, nearly 1300 additional Cambridge PhD theses are now available on request in the Apollo repository.

Prior to being made available in the repository, these Cambridge theses were held on microfilm at the British Library. They date from the 1960s through to 2008, when digitisation took over from microfilm as a means of document storage. The British Library holds 14,000 Cambridge PhD theses on microfilm; in 2016 they embarked on a project with the OSC to digitise ten percent of the collection at low cost – read more about this in an earlier post, Choosing from a cornucopia: a digitisation project.

You can explore the collection in Apollo: Historical Digital Theses: British Library collection. The theses are under controlled access, which means they are available on request for non-commercial research purposes, subject to a £15 admin fee.

Establishing access levels

We established that the level of access we could allow to the thesis could be determined by the route a thesis entered the repository, its content, or in some cases the author’s wish to publish. To address all of the potential issues, we decided to define a set of access levels which would determine what we, as managers of the repository, were able to do with a thesis and the way in which it could be accessed by a requestor.

The access levels were put in action in spring 2018 and this was followed by a survey of Degree Committees, conducted by the e-theses working group consisting of members of the University Library and Student Registry. The survey asked for feedback on the suitability of the access levels for research outputs for all departments in the University; the outcome confirmed that the access levels were working and covered the options well, although a few tweaks were needed. In light of the feedback, a set of recommendations was put to the Board of Graduate Studies by the e-theses working group, and these recommendations were considered and accepted at their meeting on 3 July 2018, ready to be put in place for the 2018/19 academic year.

eSales for theses under controlled access

At the same time as we were establishing our access levels, we were also working on devising an eSales process to facilitate the supply of theses under controlled access. Controlled access replicates the way that historical, hardbound theses were managed in the library, with the addition of an electronic version of the thesis being held in the repository, and follows the library copy and supply rules for unpublished works under copyright law. A thesis scanned by the library would be deposited under controlled access so it remains unpublished, but this access level is also available to students depositing their thesis directly. The eSales process we devised went live in July 2018 and this meant a large number of theses held in the repository were made more accessible, including those digitised by the British Library. As of 18 October, we have supplied 14 theses via the eSales route and the requests keep coming in at a steady pace.

Looking forward to the 2018/19 academic year

As we begin the 2018/19 academic year, our theses management is looking in good shape but we will continue to improve and refine our internal and external services. In consultation with the University’s Student Registry we are making the final changes to our deposit forms, access levels and communications and we endeavour to make this academic year the smoothest yet for e-theses management. University of Cambridge theses are more accessible than they have ever been. The collection will grow as more students deposit each year, and the valuable research of PhD students will continue to be disseminated.