As part of Open Access Week 2018, the Office of Scholarly Communication is publishing a series of blog posts on open access and open research. In this post Dr Mélodie Garnier provides some new insights into our Request a Copy service.

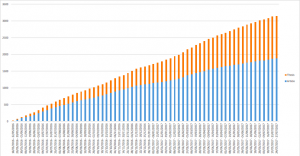

4,416. This is the number of requests for copies of material in our repository we’ve received over the past 12 months. Daunting, isn’t it? And definitely on the rise, with a 33% increase from the previous year. Two years and a half after its implementation in June 2016, our Request a Copy service is now more popular than ever. Our institutional repository Apollo hosts thousands of freely available research outputs, but also many that are under embargo. People from all over the world and from all walks of life are keen to access them. But what exactly do requesters want? And why do they want it?

What do people want?

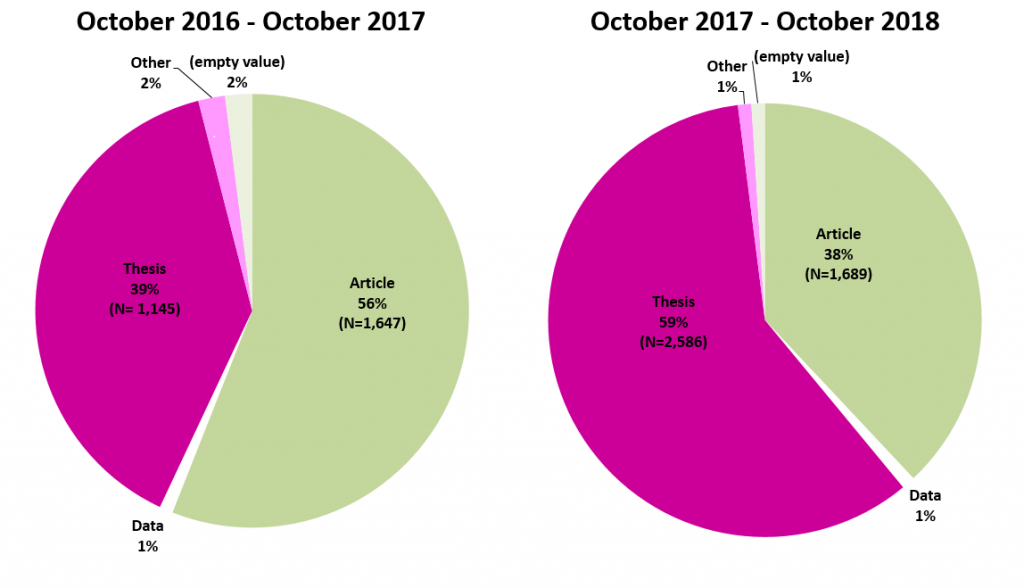

Our repository hosts a whole range of research outputs, but theses and journal articles are by far the most popular. Interestingly, the relative proportion of requested theses vs requested articles has shifted this year. From October 2016 to October 2017, requests for journal articles made up 56% of the total number of requests, and requests for theses made up 39%. Since last October, requests for journal articles have accounted for 38% of the total while theses have accounted for 59%.

Looking at the raw figures, the number of requests for journal articles has actually gone up (from 1,647 to 1,689), though only slightly. But the number of thesis requests has more than doubled, going from 1,145 to 2,586. This is partly explained by the University of Cambridge’s requirement for PhD students to upload their theses from 1st October 2017, leading to 1,279 new theses uploads. On top of these, we have added around 1,300 historical British Library theses and around 200 scanned historical theses from the Digital Content Unit. So between 2,500 and 3,000 theses have been added to Apollo this year alone (more on this tomorrow for #ThesisThursday).

Most wanted

Most items requested this year were only requested once, but 28 items were requested 10 times or more. Of the 20 most requested items, four are journal articles and 16 are PhD theses. Here’s our top 5:

- Imperial succession in Tang China, 618-762 (2010) (thesis – Asian and Middle Eastern Studies) (24 requests)

- A Review of User Interface Design for Interactive Machine Learning (2018) (article – Engineering) (22 requests)

- Living the Law of Origin: The Cosmological, Ontological, Epistemological, and Ecological Framework of Kogi Environmental Politics (2018) (thesis – Social Anthropology) (21 requests)

- Family language policy and practice as parental mediation of habitus, capital and field: an ethnographic case-study of migrant families in England (2018) (thesis – Education) (18 requests)

- The environmental costs and benefits of high-yield farming (2018) (article – Zoology) (16 requests)

Aside from the gold medal winner, all the other works were published this year and have only been available in Apollo for a few months. So it is striking to see how popular some of them have become in quite a short period of time. A case in point is the zoology article, which was deposited in Apollo only last month and first published shortly afterwards.

Word of mouth

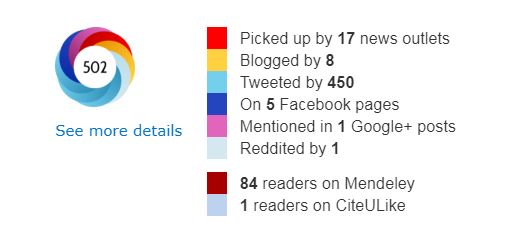

Though it is sometimes unclear why particular outputs suddenly attract a lot of requests, Altmetric Attention scores can be telling – see the one below for the zoology article I’ve just mentioned:

Another interesting example (not included in the top 5) is a PhD thesis deposited in Apollo at the end of August. From 18 in September, the Apollo record has gone up to an astounding number of 911 visits in October (and counting), with a surge of requests. What happened in between? The author publicised her thesis on a Facebook society page, pointing to the repository record link for access.

We only became aware of this as requesters explicitly referred to that page, but it’s possible that similar things happen a lot of the time. So aside from traditional media outlets, the influence of social media on number of requests received can be quite dramatic, and probably greater than we could ever capture.

Tell us about yourself

When requesting a copy of an embargoed article or thesis, people are prompted to leave a message alongside contact details. This is so they can introduce themselves and explain why they are interested in accessing the work, mainly so that authors can make informed decisions on whether to accept or reject requests. Quite often these messages have little to no useful information, but some can be informative in a number of ways.

Through them we can get a glimpse of the range of people accessing the repository – their geographical provenance, background and professional occupation. We can also get a sense of the range of interests that people have (which may appear very specialised, if not a little obscure). And crucially they tell us what people want to do with the research – whether use it as reference, apply it in their professional sphere or simply read it for pleasure.

Why do people request work?

Broadly speaking, people request work in Apollo for the following purposes: reference/citation, personal interest/leisure, replication of results for research purposes, and need to inform professional practice. But those broad categories can include several sub-categories, for example personal interest can stem from hearing about the research in the media or knowing the author.

Getting the full detailed account of why people request work from our repository would require going through messages individually, and perhaps some degree of subjective judgement. Since launching the Request a Copy service we’ve had over 8,000 requests – so even if uninformative messages were excluded, the analysis could be fairly time-consuming. But certainly worth exploring, so watch this space.

Just a snippet…

What better way to advocate for Open Access than to show concrete examples of how research can impact on individual lives? Our Open Access team sees evidence of this every day through Request a Copy messages. So until we can offer a full-blown analysis of the output, let’s conclude this blog post with a selection of favourites:

- “Our daughter is being investigated for Beckwith Wiedemann Syndrome. We would like as much information as possible about this area”

- “I’m a pediatric radiation oncologist and this paper is a “practice changer” one!”

- “My task is to convince policy makers in Sri Lanka to switch to circular economy. I am looking for all possible information to do this”

- “I work in FE/HE and have a number of students experiencing/ or diagnosed with psychosis, I am very interested in intervention research and programmes for psychosis that can be implemented within our college environment”

- “I would like a copy of this material for inspiring my high school students of physics”

- “I hope to learn more about the potential risks of my decision to donate a kidney”

Although there is a definite cost to running Request a Copy in terms of staff time, it is clear how popular and valuable a service it has become. As its popularity increases so does the need for process efficiency, however. This is currently a big priority for us and something we’ll have to keep working on, but we think the benefits for researchers and the wider community are worth it.