Authors: Emma Gilby, Matthias Ammon, Rachel Leow and Sam Moore

This is the third of a series of blog posts, presenting the reflections of the Working Group on Open Research in the Humanities. Read the opening post at this link. The working group aimed to reframe open research in a way that was more meaningful to humanities disciplines, and their work will inform the University of Cambridge approach to open research. This post reflects on the concept of FAIR data and proposes an alternative way of thinking about data in the humanities.

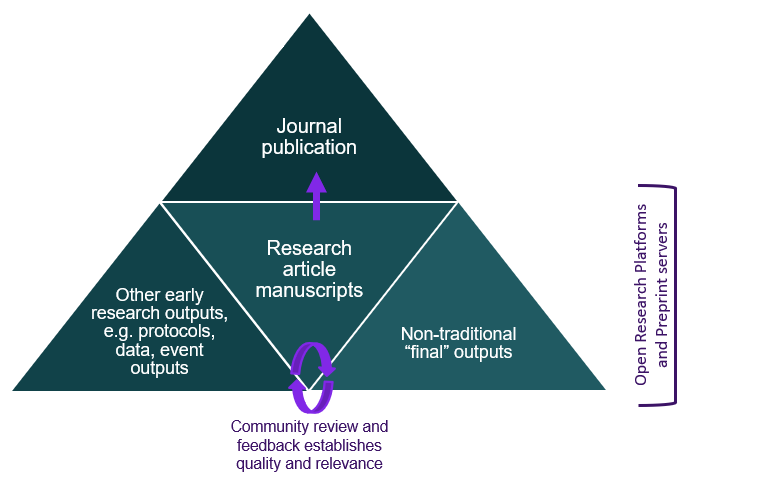

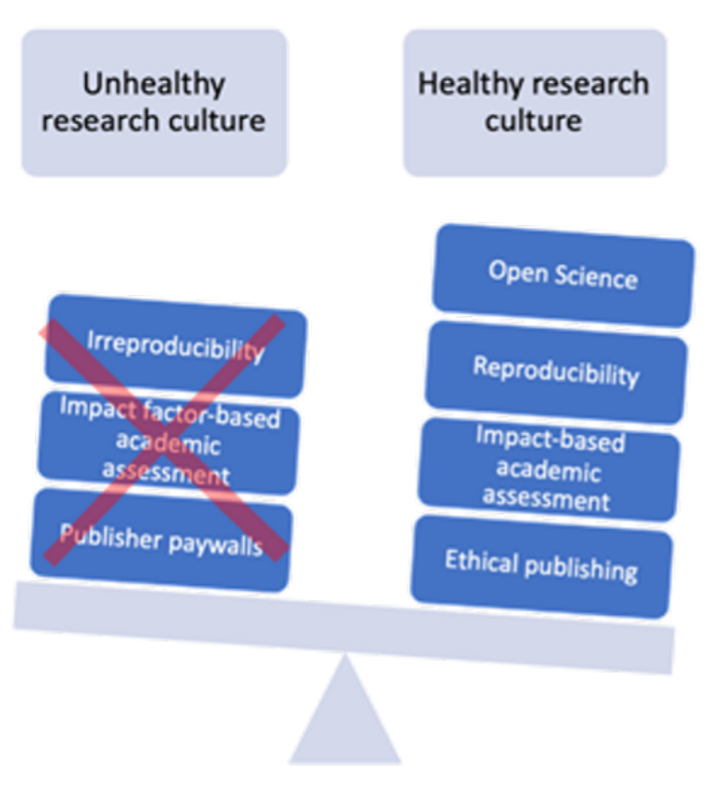

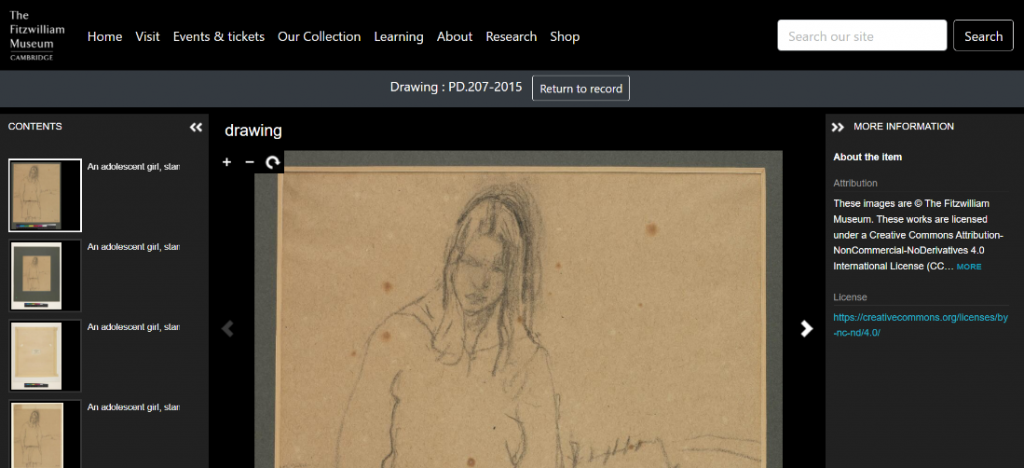

As a rule, data in the arts and humanities is collected, organised, recontextualised and explained. We are therefore putting forward this acronym as an alternative to LERU’s FAIR data (findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable). Our data is collected rather than generated; organised and recontextualised in order to further a cultural conversation about discoveries, methods and debates; and explained as part of the analytical process. Any view of scholarly comms as uniquely about the distribution of and access to FAIR data (‘from my bench to yours’) will seem less relevant to A&H academics. Similarly, the goal of reproducibility of data – in the sense in which this often appears in the sciences and social sciences, where it refers to the results of a study being perfectly replicable when the study is repeated – is, if anything, contrary to the aim of CORE data: i.e. the aim that this data should be built upon and thereby modified through the process of further recontextualization. Our CORE data, then, understood as information used for reference and analysis, is made up of texts, music, pictures, fabrics, objects, installations, performances, etc. Sometimes, this information does not belong to us, but is owned by another person or institution or community, in which case it is not ours to make public.

Opportunities

The A&H tend to bring information together in new ways to further discussion about socio-cultural developments across the globe. Available digital data is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the material that is worked with.[1] Arts and humanities scholars, who spend their lives thinking about the arrangement and communication of information, are acutely aware that archives (digital and otherwise) are not neutral spaces, but man-made and the product of human choices. This means that information available online, to a broadband-enabled public, is asymmetrical and distorted.

One of the main benefits of open research is that it is thought to make data globally accessible, especially to ‘the global south’ and to institutions with fewer available funds to ‘buy data in’. As we explore below (‘research integrity’), this unidirectional view of open access is problematic. In general, digital material tends to reproduce English-speaking structures and epistemologies. As FAIR data is redefined as CORE data, an attention to context will hopefully promote the diverse positions occupied by all those who make up the world and who produce research about it.

Support required

In order usefully to employ CORE data in the A&H, we need to bring to the surface and examine underlying assumptions about knowledge creation as well as knowledge dissemination.

The work of the digital humanities – rooted explicitly in digital technologies and the forms of communication that they enable – is obviously a vital part of these discussions about opening up the CORE data of the humanities. Digital work, in the same way as any other successful A&H research, needs to consider its own materiality and conditions of production, evaluate its own history, draw attention to its own limits, and navigate its trans-temporal relationships with data in other forms (the manuscript, the printed text, the painting, the piece of music). This is a developing field and one that still has an uneasy relationship with the existing tenure/promotions system.[2] Colleagues noted that training needs are evolving constantly. It is often hard to know where to turn for specific guidance in e.g. how to manage one’s own ‘born digital’ archives, how to deconstruct a twitter archive, and so on.

This issue also overlaps with the need, as part of the ‘rewards and incentives’ process outlined below, to evaluate the success of colleagues as they undertake this training and negotiate with these processes. DH is one of the most exciting and rapidly developing areas of research and needs to be widely resourced. But it would also be harmful to collapse all A&H research into ‘the digital humanities’. The work of colleagues whose CORE data is resistant, for whatever reason, to wide online dissemination in English also needs to be allocated the value it deserves: some publics are simply smaller than others.

Postscript: the group subsequently became aware of the CARE Principles of Indigenous Data Governance. These principles will also be considered when developing our services in support of data management and ethical sharing.

[1] Erzsébet Tóth-Czifra, ‘The Risk of Losing the Thick Description: Data Management Challenges Faced by the Arts and Humanities in the Evolving FAIR Data Ecosystem’, in Digital Technologies and the Practices of Humanities Research, edited by Jennifer Edmond (Open Book Publishers, 2014), https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0192.10

[2]See the excellent article by Cait Coker and Kate Ozment ‘Building the Women in Book History Bibliography, or Digital Enumerative Bibliography as Preservation of Feminist Labor’, Digital Humanities Quarterly 13 (3), 2019, http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/13/3/000428/000428.html – where the authors of the ‘Women in Book History’ digital bibliography still see the tenure system as ‘monograph-driven’, and had to fund their research through selling merchandise.