The Open Research at Cambridge conference took place between 22–26 November 2021. In a series of talks, panel discussions and interactive Q&A sessions, researchers, publishers, and other stakeholders explored how Cambridge can make the most of the opportunities offered by open research. This blog is part of a series summarising each event.

The opening session, chaired by Dr Jessica Gardner (University Librarian and Director of Library Services) included talks by Professor Anne Ferguson-Smith (Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Research), Professor Steve Russell (Acting Head of Department of Genetics and Chair of Open Research Steering Committee), Mandy Hill (Managing Director of Academic Publishing at Cambridge University Press) and Dr Neal Spencer (Deputy Director for Collections and Research at the Fitzwilliam Museum). All four speakers foresee an increasingly open future, with benefits for both institutions and researchers. They also considered some of the challenges that still need to be worked through to avoid potential problems.

What is working well?

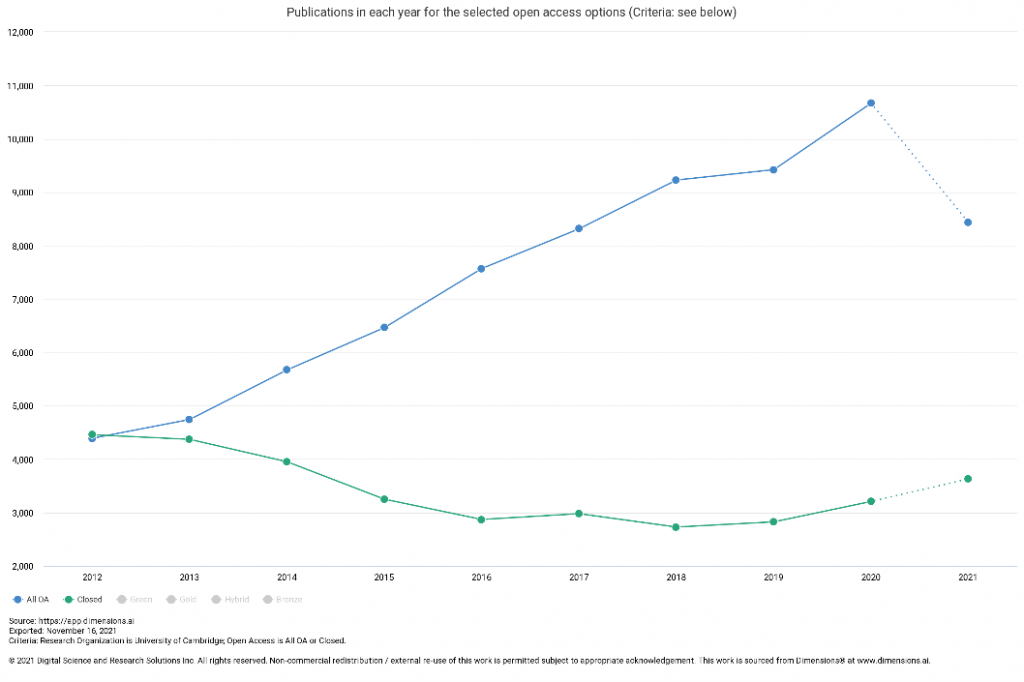

In recent years, we have made great progress in the proportion of publications that are open access. Over three quarters of publications with Cambridge authors last year were openly available in some form.

The trend is continuing and it is not unique to our institution. CUP have set an ambitious goal for the vast majority of research articles they publish to be open access by 2025.

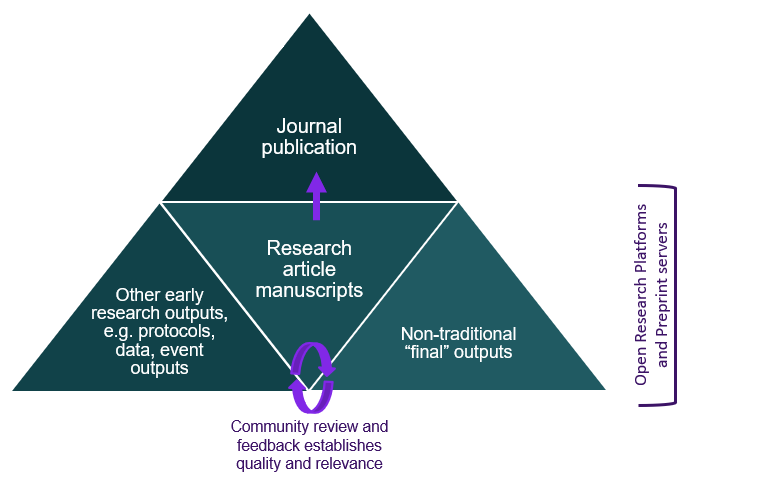

Other forms of publication are becoming common, meeting different dissemination needs. Preprints have been the star of the show during the pandemic, allowing rapid dissemination while formal peer review follows down the line.

Diagram from Mandy Hill’s slide: ‘Increasingly open platforms and formal publishing will meet different dissemination needs’

In the scholarly communication arena, open access articles benefit from more downloads and citations. Museum-based projects involving artisans, schools and artists all found enthusiastic responses.

What can we look forward to?

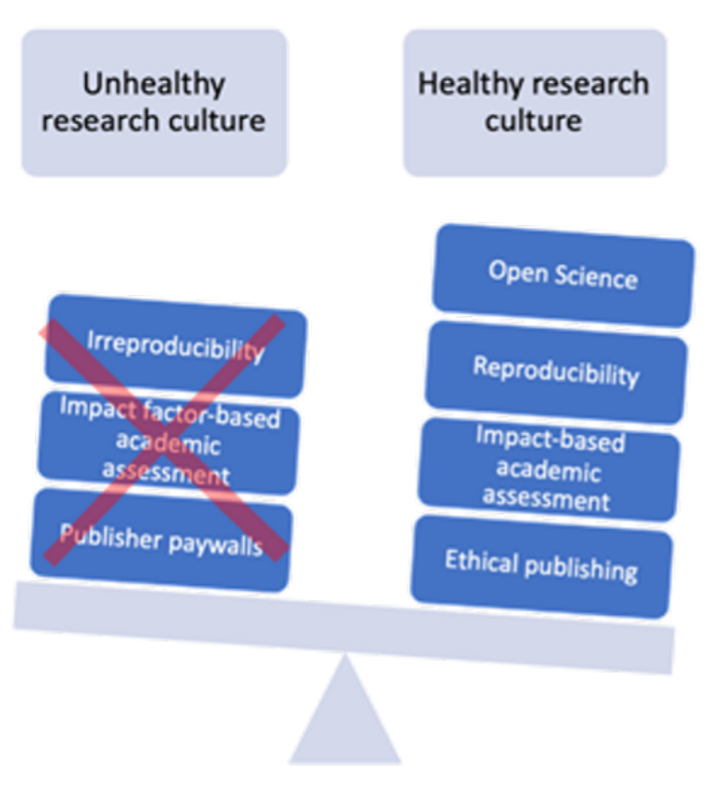

Research culture is coming under the spotlight across the sector, and Cambridge has committed to an ambitious action plan to create a thriving environment to do research. Key principles include openness, collaboration, inclusivity, and fair recognition of all contributions.

Diagram from Prof Steve Russell: ‘Going Forward’

Implementing the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) is part of this progress. We want to assess research on its own merits rather than on the basis of journal or publisher metrics. This also means recognising all research outputs and a broad range of impacts.

Reproducibility is increasingly recognised as critical in a number of disciplines. A developing UKRN group within the University aims to ‘take nobody’s word for it’ – but rather support reproducible workflows that underpin confidence in the conclusions of research. By sharing and rewarding best practice we can become world leaders in this area, and in open research more widely.

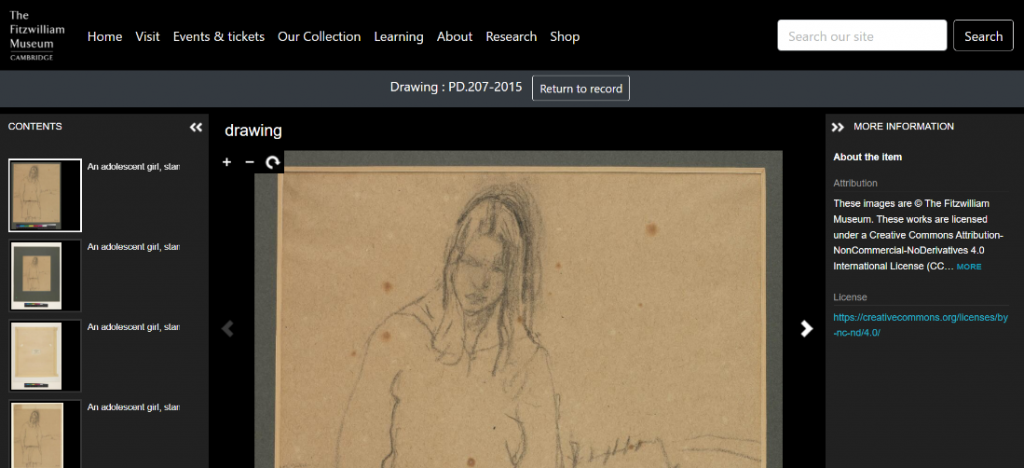

In the past, museum collections have tended to be documented in limited ways, with poor accessibility and interoperability, which made it hard to discover and use materials. Several exciting projects at the Fitzwilliam Museum and more broadly have started to change that. There are opportunities for a single discovery portal, tying together different collections. The Fitzwilliam Museum is also making its collection discovery process richer, by providing opportunities for deeper dives, and more connected, by linking with other collections and resources.

Deep zoom access to an image in the Fitzwilliam collection. Adapted from Dr Neal Spencer’s slide ‘Fitzwilliam Museum Collections Search’.

What problems should we be mindful of?

There are still barriers that hinder some open research aspirations. Historical constraints on the ways we find materials, conduct research, and publish results remain. Some systems may need to be reimagined, while not scrapping structures that are still serving us well.

Cambridge is a large and complex institution, where change takes time. Nevertheless, there is an established governance structures and an evolving set of policies that support open research.

Most importantly, researchers should be at the centre of the move towards open research. It is important that they benefit from open practices, rather than finding themselves torn between competing priorities. Conversations continued throughout the week to explore possible approaches in different disciplines, drawing from the rich diversity of experiences to shape the future of open research at Cambridge.