On the 4 November the Research Data Facility at Cambridge University invited some inspirational leaders in the area of research data management and asked them to address the question: “is open data moving science forward or a waste of money & time?”. Below are Dr Marta Teperek’s impressions from the event.

Great discussion

Want to initiate a thought-provoking discussion on a controversial subject? The recipe is simple: invite inspirational leaders, bright people with curious minds and have an excellent chair. The outcome is guaranteed.

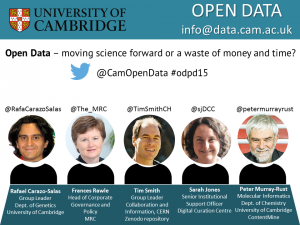

We asked some truly inspirational leaders in data management and sharing to come to Cambridge to talk to the community about the pros and cons of data sharing. We were honoured to have with us:

Rafael Carazo-Salas, Group Leader, Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge

Rafael Carazo-Salas, Group Leader, Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge

@RafaCarazoSalas- Sarah Jones, Senior Institutional Support Officer from the Digital Curation Centre; @sjDCC

- Frances Rawle, Head of Corporate Governance and Policy, Medical Research Council; @The_MRC

- Tim Smith, Group Leader, Collaboration and Information Services, CERN/Zenodo; @TimSmithCH

- Peter Murray-Rust, Molecular Informatics, Dept. of Chemistry, University of Cambridge, ContentMine; @petermurrayrust

The discussion was chaired by Dr Danny Kingsley, the Head of Scholarly Communication at the University of Cambridge (@dannykay68).

What is the definition of Open Data?

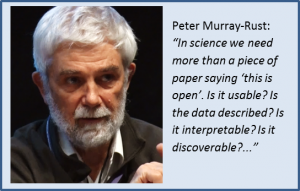

The discussion started off with a request for a definition of what “open” meant. Both Peter and Sarah explained that ‘open’ in science was not simply a piece of paper saying ‘this is open’. Peter said that ‘open’ meant free to use, free to re-use, and free to re-distribute without permission. Open data needs to be usable, it needs to be described, and to be interpretable. Finally, if data is not discoverable, it is of no use to anyone. Sarah added that sharing is about making data useful. Making it useful also involves the use of open formats, and implies describing the data. Context is necessary for the data to be of any value to others.

The discussion started off with a request for a definition of what “open” meant. Both Peter and Sarah explained that ‘open’ in science was not simply a piece of paper saying ‘this is open’. Peter said that ‘open’ meant free to use, free to re-use, and free to re-distribute without permission. Open data needs to be usable, it needs to be described, and to be interpretable. Finally, if data is not discoverable, it is of no use to anyone. Sarah added that sharing is about making data useful. Making it useful also involves the use of open formats, and implies describing the data. Context is necessary for the data to be of any value to others.

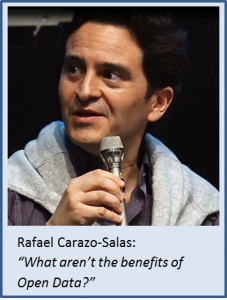

What are the benefits of Open Data?

Next came a quick question from Danny: “What are the benefits of Open Data”? followed by an immediate riposte from Rafael: “What aren’t the benefits of Open Data?”. Rafael explained that open data led to transparency in research, re-usability of data, benchmarking, integration, new discoveries and, most importantly, sharing data kept it alive. If data was not shared and instead simply kept on the computer’s hard drive, no one would remember it months after the initial publication. Sharing is the only way in which data can be used, cited, and built upon years after the publication. Frances added that research data originating from publicly funded research was funded by tax payers. Therefore, the value of research data should be maximised. Data sharing is important for research integrity and reproducibility and for ensuring better quality of science. Sarah said that the biggest benefit of sharing data was the wealth of re-uses of research data, which often could not be imagined at the time of creation.

Next came a quick question from Danny: “What are the benefits of Open Data”? followed by an immediate riposte from Rafael: “What aren’t the benefits of Open Data?”. Rafael explained that open data led to transparency in research, re-usability of data, benchmarking, integration, new discoveries and, most importantly, sharing data kept it alive. If data was not shared and instead simply kept on the computer’s hard drive, no one would remember it months after the initial publication. Sharing is the only way in which data can be used, cited, and built upon years after the publication. Frances added that research data originating from publicly funded research was funded by tax payers. Therefore, the value of research data should be maximised. Data sharing is important for research integrity and reproducibility and for ensuring better quality of science. Sarah said that the biggest benefit of sharing data was the wealth of re-uses of research data, which often could not be imagined at the time of creation.

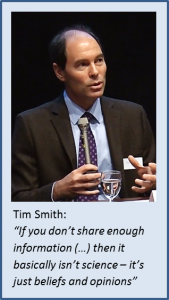

Finally, Tim concluded that sharing of research is what made the wheels of science turn. He inspired further discussions by strong statements: “Sharing is not an if, it is a must – science is about sharing, science is about collectively coming to truths that you can then build on. If you don’t share enough information so that people can validate and build up on your findings, then it basically isn’t science – it’s just beliefs and opinions.”

Tim also stressed that if open science became institutionalised, and mandated through policies and rules, it would take a very long time before individual researchers would fully embrace it and start sharing their research as the default position.

Tim also stressed that if open science became institutionalised, and mandated through policies and rules, it would take a very long time before individual researchers would fully embrace it and start sharing their research as the default position.

I personally strongly agree with Tim’s statement. Mandating sharing without providing the support for it will lead to a perception that sharing is yet another administrative burden, and researchers will adopt the ‘minimal compliance’ approach towards sharing. We often observe this attitude amongst EPSRC-funded researchers (EPSRC is one of the UK funders with the strictest policy for sharing of research data). Instead, institutions should provide infrastructure, services, support and encouragement for sharing.

Big data

Data sharing is not without problems. One of the biggest issues nowadays it the problem of sharing of big data. Rafael stressed that with big data, it was extremely expensive not only to share, but even to store the data long-term. He stated that the biggest bottleneck in progress was to bridge the gap between the capacity to generate the data, and the capacity to make it useful. Tim admitted that sharing of big data was indeed difficult at the moment, but that the need would certainly drive innovation. He recalled that in the past people did not think that one day it would be possible just to stream videos instead of buying DVDs. Nowadays technologies exist which allow millions of people to watch the webcast of a live match at the same time – the need developed the tools. More and more people are looking at new ways of chunking and parallelisation of data downloads. Additionally, there is a change in the way in which the analysis is done – more and more of it is done remotely on central servers, and this eliminates the technical barriers of access to data.

Personal/sensitive data

Frances mentioned that in the case of personal and sensitive data, sharing was not as simple as in basic sciences disciplines. Especially in medical research, it often required provision of controlled access to data. It was not only important who would get the data, but also what they would do with it. Frances agreed with Tim that perhaps what was needed is a paradigm shift – that questions should be sent to the data, and not the data sent to the questions.

Frances mentioned that in the case of personal and sensitive data, sharing was not as simple as in basic sciences disciplines. Especially in medical research, it often required provision of controlled access to data. It was not only important who would get the data, but also what they would do with it. Frances agreed with Tim that perhaps what was needed is a paradigm shift – that questions should be sent to the data, and not the data sent to the questions.

Shades of grey: in-between “open” and “closed”

Both the audience and the panellists agreed that almost no data was completely “open” and almost no data was completely “shut”. Tim explained that anything that gets research data off the laptop to a shared environment, even if it was shared only with a certain group, was already a massive step forward. Tim said: “Open Data does not mean immediately open to the entire world – anything that makes it off from where it is now is an important step forward and people should not be discouraged from doing so, just because it does not tick all the other checkboxes.” And this is yet another point where I personally agreed with Tim that institutionalising data sharing and policing the process is not the way forward. To the contrary, researchers should be encouraged to make small steps at a time, with the hope that the collective move forward will help achieving a cultural change embraced by the community.

Open Data and the future of publishing

Another interesting topic of the discussion was the future of publishing. Rafael started explaining that the way traditional publishing works had to change, as data was not two-dimensional anymore and in the digital era it could no longer be shared on a piece of paper. Ideally, researchers should be allowed to continue re-analysing data underpinning figures in publications. Research data underpinning figures should be clickable, re-formattable and interoperable – alive.

Danny mentioned that the traditional way of rewarding researchers was based on publishing and on journal impact factors. She asked whether publishing data could help to start rewarding the process of generating data and making it available. Sarah suggested that rather than having the formal peer review of data, it would be better to have an evaluation structure based on the re-use of data – for example, valuing data which was downloadable, well-labelled, re-usable.

Danny mentioned that the traditional way of rewarding researchers was based on publishing and on journal impact factors. She asked whether publishing data could help to start rewarding the process of generating data and making it available. Sarah suggested that rather than having the formal peer review of data, it would be better to have an evaluation structure based on the re-use of data – for example, valuing data which was downloadable, well-labelled, re-usable.

Incentives for sharing research data

The final discussion was around incentives for data sharing. Sarah was the first one to suggest that the most persuasive incentive for data sharing is seeing the data being re-used and getting credit for it. She also stated that there was also an important role for funders and institutions to incentivise data sharing. If funders/institutions wished to mandate sharing, they also needed to reward it. Funders could do so when assessing grant proposals; institutions could do it when looking at academic promotions.

The final discussion was around incentives for data sharing. Sarah was the first one to suggest that the most persuasive incentive for data sharing is seeing the data being re-used and getting credit for it. She also stated that there was also an important role for funders and institutions to incentivise data sharing. If funders/institutions wished to mandate sharing, they also needed to reward it. Funders could do so when assessing grant proposals; institutions could do it when looking at academic promotions.

Conclusions and outlooks on the future

This was an extremely thought-provoking and well-coordinated discussion. And maybe due to the fact that many of the questions asked remained unanswered, both the panellists and the attendees enjoyed a long networking session with wine and nibbles after the discussion.

From my personal perspective, as an ex-researcher in life sciences, the greatest benefit of open data is the potential to drive a cultural change in academia. The current academic career progression is almost solely based on the impact factor of publications. The ‘prestige’ of your publications determines whether you will get funding, whether you will get a position, whether you will be able to continue your career as a researcher. This, connected with a frequently broken peer-review process, leads to a lot of frustration among researchers. What if you are not from the world’s top university or from a famous research group? Will you be able to still publish your work in a high impact factor journal? What if somebody scooped you when you were about to publish results of your five years’ long study? Will you be able to find a new position? As Danny suggested during the discussion, if researchers start publishing their data in the ‘open”’ there is a chance that the whole process of doing valuable research, making it useful and available to others will be rewarded and recognised. This fits well with Sarah’s ideas about evaluation structure based on the re-use of research data. In fact, more and more researchers go to the ‘open’ and use blog posts and social media to talk about their research and to discuss the work of their peers. With the use of persistent links research data can be now easily cited, and impact can be built directly on data citation and re-use, but one could also imagine some sort of badges for sharing good research data, awarded directly by the users. Perhaps in 10 or 20 years’ time the whole evaluation process will be done online, directly by peers, and researchers will be valued for their true contributions to science.

And perhaps the most important message for me, this time as a person who supports research data management services at the University of Cambridge, is to help researchers to really embrace the open data agenda. At the moment, open data is too frequently perceived as a burden, which, as Tim suggested, is most likely due to imposed policies and institutionalisation of the agenda. Instead of a stick, which results in the minimal compliance attitude, researchers need to see the opportunities and benefits of open data to sign up for the agenda. Therefore, the Institution needs to provide support services to make data sharing easy, but it is the community itself that needs to drive the change to “open”. And the community needs to be willing and convinced to do so.

Further resources

- Click here to see the full recording of the Open Data Panel Discussion.

- And here you can find a storified version of the event prepared by Kennedy Ikpe from the Open Data Team.

Thank you

We also wanted to express a special ‘thank you’ note to Dan Crane from the Library at the Department of Engineering, who helped us with all the logistics for the event and who made it happen.

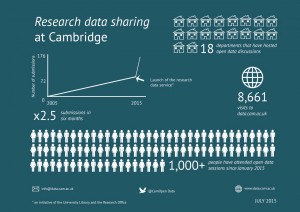

This infographic demonstrates how successful the Research Data Facility has been. Prepared by Laura Waldoch from the University Library, it is

This infographic demonstrates how successful the Research Data Facility has been. Prepared by Laura Waldoch from the University Library, it is