Dr. Samuel Moore, Scholarly Communication Specialist, Cambridge University Libraries

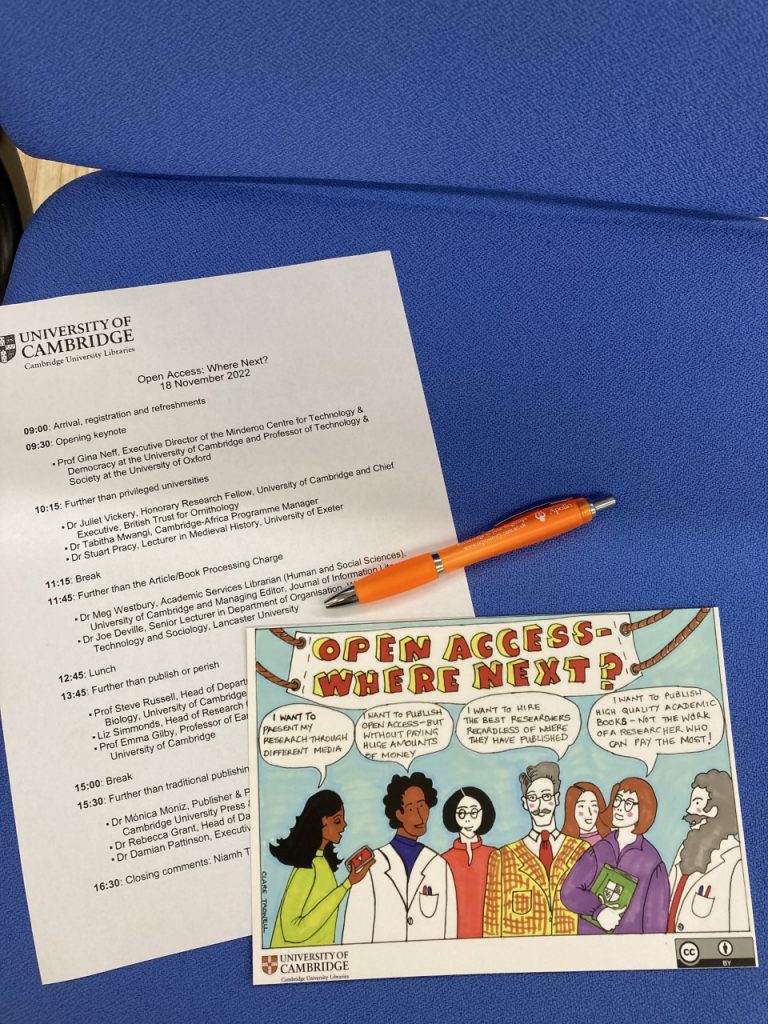

On Friday 18th November, participants from across Cambridge and beyond gathered for a hybrid meeting on the future of open access publishing. Hosted by Homerton College, ‘Open Access: Where Next?’ explored issues relating to article-processing charges, research assessment and innovation in scientific publishing. 65 in-person attendees and 78 online attendees participated in the day-long event consisting of four panels and a keynote from Professor Gina Neff of the Minderoo Centre for Technology and Democracy.

Prof. Neff kicked off the event with a timely and insightful talk titled ‘Further than the academy: the stakes for open research’. Covering themes such as misinformation, preservation and widening participation in knowledge, Prof. Neff explored the importance of democratic and responsible approaches to our digital present and future, looking especially to libraries as key to supporting these issues.

The first panel of the day, ‘Further than privileged universities’, was introduced by Dr. Matthias Ammon and featured Dr. Juliet Vickery, Chief Executive of the British Trust for Ornithology, Dr. Tabitha Mwangi, Cambridge-Africa Programme Manager, and Dr. Stuart Pracy, Lecturer in Medieval History at the University of Exeter. Each panellist spoke on the challenges of open access that arise from either being outside privileged university spaces or without secure employment within them. Despite representing quite different communities, there were a number of commonalities between the experiences of each speaker, most notably the fact that moving from paying to access scholarly material to paying to publish it added a new exclusionary dimension to their ability to communicate research.

In the second panel, we heard from three speakers who are working against the move toward paying to publish. ‘Further than APCs and BPCs’ featured speakers working on publishing projects that do not require authors to pay processing charges to publish their work – so-called Diamond open access. Cambridge librarians Dr Meg Westbury (Academic Services Librarian, Human and Social Sciences) and Dr Yvonne Nobis (Head of Physical Sciences libraries) described their respective publishing projects, The Journal of Information Literacy and Discrete Analysis. The audience learned about both the challenges around running a journal on a shoestring, but also the advantages of a DIY approach to publishing without recourse to expensive publishing networks. In addition, Dr. Joe Deville of Lancaster University explained the work of the soon-to-launch Open Book Collective to collaboratively fund the publication of open access books in the humanities and social sciences.

After lunch, Niamh Tumelty chaired a roundtable with Cambridge researchers on research assessment and its relationship with publishing. Prof. Steve Russell, Head of Department of Genetics, described his work as Chair of DORA (the Declaration on Research Assessment) alongside the work needed for the university to fulfil its commitment to ensuring researchers are no longer judged by the venues in which they publish. Following this, Liz Simmonds – the University’s Head of Research Culture – described the pros and cons of alternative approaches to assessment such as narrative CVs. Finally, Prof. Emma Gilby of the Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages and Linguistics explained the view from the humanities, particularly how declarations such as DORA are designed and implemented with the sciences in mind.

The final panel of the day was on innovations in scholarly publishing. Chaired by Dr. Samuel Moore, three panellists described their publishing approaches to moving beyond the traditional journal article. Dr. Mónica Moniz of Cambridge University Press & Assessment presented Research Directions – the press’ approach to publishing the research lifecycle across a variety of disciplinary questions. Following this, F1000’s Head of Data and Software Publishing, Dr. Beck Grant, described the publisher’s approach to automated data publishing in partnership with the Wellcome Sanger Institute. Finally, Dr. Damian Pattinson discussed eLife’s new approach to removing accept/reject decisions from its publishing process – and an invigorating discussion ensued!

At the end of the day, Niamh Tumelty summarised the event and reminded participants to fill out the postcards they were given at the start of the day to document what actions they will take in response to the issues covered in the conference. We will be posting these postcards to participants in January as a reminder of what you planned to do (with vouchers to three lucky recipients). Special thanks to all participants, attendees and organisers, but especially to Bea Gini for all her help with this, her last, event as part of the Office of Scholarly Communication. Thanks also to Clare Trowell for designing our postcards.