As part of the Office of Scholarly Communication Open Access Week celebrations, we are uploading a blog a day written by members of the team. Friday contains some observations from Dr Lauren Cadwallader on the bigger picture.

For researchers new to Open Access, it can often feel like policies are imposed on them by their institution. This is possibly because the wider context of Open Access has not been explained or revealed to them.

In a recent workshop held by the Office of Scholarly Communication we were asked “whether Open Access was just a UK thing and that the rest of the world were benefiting from the research funded by the taxes that we pay”. The answer is NO! Open Access is a global movement and involves both developed and developing countries. It is true that other people can benefit from our research but we can also benefit from theirs.

In the beginning…

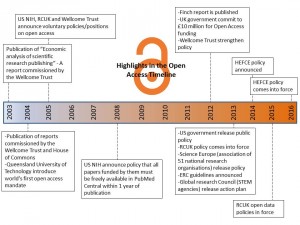

The Open Access movement as it stands today had its beginnings in 2003 in a report commissioned by the Wellcome Trust on the economics on scientific research funding. Subsequent reports in 2004 by the Wellcome Trust and the House of Commons looked at the viability of alternatives to the subscriber-pays model used by journals. Over the other side of the world Queensland University of Technology in Australia introduced the world’s first University-wide open access mandate in 2004. Since this was introduced they have seen a correlation between research being open access and the rise in the ranking of the university.

Following this, the US National Institute of Health, RCUK and the Wellcome Trust all released policies on open access in 2005. The next major development occurred in 2012 with the release of the Finch report, which has really set the scene for open access in the UK. Since then the open access movement has grown and spread around the world to both developed and developing countries. There is a potted history of open access listed here.

Open Access globally

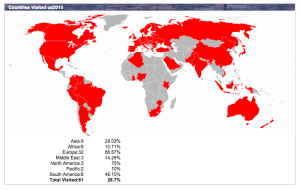

Sixty-one countries have open access policies or repositories. Funders and governments throughout Europe, North America and Australia have open access policies already in place:

- Mexico has a national legislation relating to open access

- the Indian Department of Biotechnology and the Department of Science and Technology released its Open Access policy last year

- the Chinese Academy of Sciences has its own policy – to name but a few.

ROARMAP, the Registry of Open Access Repository Mandates and Policies, lists 730 policies that are active in 2014-15.

Map of countries listed on ROARMAP – registry of Open Access Repository Mandates and Policies – available here

Fourteen countries – Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Spain, Mexico, Peru, Portugal, South Africa, Uruguay and Venezuela – have come together to form the SciELO network – an Open Access repository of papers published by over 1000 journals from these countries and SciELO has been active for over 15 years.

Statistics from university repositories can give us an idea of who in the world is accessing Open Access articles. Harvard’s repository DASH has had over 21,000 downloads from Nigeria and 350,000 from the UK. The repository of the Universidad de Los Andes in Venezuela – whose motto is ¡concimiento libre! (free knowledge!) – has had over 2 million downloads from users in the US since 2008 and almost 38,000 from the UK.

This goes to show that there is a two-way (or rather multi-way) knowledge transfer between countries.

Benefits to All

So, what are the benefits of this two-way knowledge share? What do the UK tax payers gain?

Benefits of open access: A high resolution of this graphic is downloadable here

In academia itself open access can have an impact on a researcher’s visibility. Papers that are open access are more likely to be cited by other researchers and more like to be shared on the internet in blogs, news outlets and social media. This all raises the profile of the researcher and their metric scores – an increasingly important tool for deciding who gets funding or hired in some universities.

Individuals carrying out research – academics, school children, professionals in industry – can gain access to knowledge that they might otherwise not be able to get. The Harvard repository, DASH, encourages users to leave their personal stories of using the repository to access open access material. For example, a potential PhD student from the UK accessed papers to strengthen their application to Oxford; a nurse working in a remote Australian aboriginal community could pursue her interests in literature; a journalist in Mexico has been able to access material on the history of Mexican books that they otherwise wouldn’t have been able to get.

These stories give us a handle on how the research is used and the impact that Open Access can have beyond academia. In the future we are hoping to record stories like this from our own repository, Apollo.

UK taxpayers benefit from Open Access research because it can be used to make a difference to society and the economy. Research can influence public policy, industry can draw on ideas that propel their work forward, universities’ research profile is raised making them more likely to attract funding and the brightest minds, medical advancements can be made. For example, openly available research was used by a 15 year old schoolboy in the US to invent an inexpensive early detection test for pancreatic, ovarian and lung cancers. Whilst no cancer-detecting 15 year olds have come to light in the UK (yet!) this demonstrates the possibilities that come with Open Access, not just for academia but for everyone.