This post looks at the University of Cambridge repository ‘Request a copy’ service from the user’s perspective in terms of uptake so far, feedback we have received, and reasons why people might request a copy of a document in our repository. You may be interested in the related blog post on our ‘Request a copy’ service, which discusses the concept behind ‘Request a copy’, the process by which files are requested, and how this has been implemented at Cambridge

Usage Statistics

The Request a Copy button has been much more successful than we anticipated, particularly because there is no actual ‘button’. By the end of September 2016 (four months after the introduction of ‘Request a copy’), we had received 1120 requests (approximately 280 requests per month), the vast majority of which were for articles (68%) and theses (28%). The remaining 4% of requests were for datasets or other types of resource. We are aware that this is a particularly quiet time in the UK academic year, and expect that the number of requests will increase now term has started again.

Of the requests for articles during this period, 38% were fulfilled by the author sending a copy via the repository, and 4% were rejected by clicking the ‘Don’t send a copy’ button. However, these figures could be misleading as a number of authors have also advised us that they have entered into correspondence with the requester to ask them for further information about who they are and why they are interested in this research. Eventually, this correspondence may result in the author emailing a copy of the paper to the requester, but as this happens outside the repository, it does not appear in our fulfilment statistics. Therefore, we suspect the figure for accepted requests is in actual fact slightly higher.

Of the articles requested during this period, 45% were yet to be published, and 55% were published but not yet available to those without a subscription to the journal. The large number of requests made prior to publication indicates the value of having a policy where articles are submitted to the repository on acceptance rather than publication – there is clearly interest in accessing this research among the wider public, and if they are able to make use of it rather than waiting during the sometimes lengthy period between acceptance and publication, this can make the research process more efficient.

Author Survey

To find out why authors might not be fulfilling requests through the repository links, Dr Lauren Cadwallader, one of our Open Access Research Advisors, sent a survey on 6 July 2016 to the 113 authors who had received requests but had not clicked on the repository link or been in touch with repository staff to advise of an alternative course of action. This survey had a 13% response rate, with 15 participants, as well as eight email responses from users who provided feedback but did not complete the survey.

The relatively low response rate is indicative of either a lack of engagement with or awareness of the process – it is possible that the request emails and survey email were dismissed as spam, or that researchers were unable to respond due to an already heavy workload. One way of addressing this could be to include some information about ‘Request a copy’ in our existing training sessions, in particular to emphasise how quick the process can be in cases where the author is happy to approve the request without needing any further information from the user. We have also been developing the wording of the email sent to the author, to explain the purpose of the service more clearly, and to make it sound like a legitimate message that is less likely to be dismissed as spam.

Of the 15 people who participated in the survey, the majority were aware that they had received an email, which shows that lack of response is not always due to emails being lost in spam filters. When asked for the reason why they did not fulfil the request via the repository link, 35% of authors replied that they had emailed the requester directly, either to send the file, to request more information, or to explain why it was not possible for them to share the file at this time. This finding is quite positive, as it indicates that over a third of these requests are indeed being followed up. Although it would be helpful to us to be able to keep track of approvals through the system, at least this means that the service is fulfilling its purpose in providing a way for authors to interact with other interested researchers, and to share their work if appropriate. In fact, one of the aspects that participants liked best about the ‘Request a copy’ service was the ability to communicate directly with the requestor.

Two authors did not respond to the request because the article was available elsewhere on the internet, such as their personal / departmental website, or a preprint server (where the restrictions relating to repositories do not apply), although they did not communicate this to the requestor. In these cases, it is definitely positive that the authors are happy to share their work; however, it does show that there is often an assumption among researchers that people interested in reading their articles will be restricted to those already in their specific disciplinary communities.

Requests from people who are unaware of sites where the research might also be made available demonstrates that there is indeed an appetite among those outside of academia, or from different subject areas. This is generally a really positive thing, as it facilitates the University’s research outputs to educate and inspire a new audience beyond the more traditional communities, and could potentially lead to new collaboration opportunities. To ensure that requestors are able to access the material, and that researchers are not bombarded with requests for documents that are already freely available, authors can provide links to any external websites that are hosting a preprint version of the article, and we will add them to the repository record.

Other responses indicated that we were not necessarily emailing the right person, as participants said that they had not approved the request because they were not the corresponding author, or because they thought a co-author had already responded. At the outset of the service, we felt that emailing as many authors as possible would increase the likelihood of receiving a response; however, the survey results show that it would be better to send requests to the corresponding author(s) only, at least in cases where it is clear who they are.

An issue we have encountered on a semi-regular basis since HEFCE’s Open Access policy came into force is that of making an article’s metadata available prior to its publication. Although HEFCE and funder policies state that an article’s repository record should be discoverable, even if the article itself must be placed under embargo based on publisher restrictions, there is concern among some authors that metadata release breaches the publisher’s press embargo. You can read about this issue in some detail here.

Receiving requests for an article via the ‘Request a copy’ service can be unsettling for authors as it demonstrates how easily the repository record can be accessed, and rather than respond to the request, they contact the Open Access team to ask for the metadata record to be withdrawn until the article is published. This demonstrates a need to communicate more clearly, both on our website and within the ‘Request a copy’ pages in the repository, what is required of authors as part of HEFCE and funder Open Access policies. We will also be more explicit in the ‘Request a copy’ emails sent to authors in stating that sharing their articles via this service will not be seen as a breach of the publisher’s embargo. In cases where the author does not wish to disseminate their article before it is published, they have the option to deny any requests they receive.

Facilitating requests

There have been several instances where press interest around an article at the point of publication has generated a large number of requests, each of which must be responded to individually by the author. This has resulted in several authors asking that we automatically approve every request rather than forwarding them on. Unfortunately this is not possible for us to do, due to the legal issues surrounding ‘Request a copy’.

It is perfectly acceptable for an author to send a copy of their article to an individual, but if a repository makes that article available to everyone who requests it before the embargo has been lifted, this would be a breach of copyright because it would be ‘systematic distribution’. While responding to multiple requests is likely to be seen as an annoyance by an already overstretched researcher, we hope that a large volume of requests will also be viewed in a positive light, as it demonstrates the interest people have in their work.

Use cases

An interesting example of a request we received was actually from one of the authors of the article, as they did not have access to a copy themselves. This raises some questions about communication between the researchers in this case, if the ‘Request a copy’ service was seen to be a better way of gaining access to the author’s own research, rather than contacting one of their co-authors.

A more surprising use case is that of a plaintiff who had lost a legal case. The plaintiff was requesting an as-yet unpublished article that had been written about the case, because the article appears to argue in favour of the plaintiff and could potentially inform a future appeal. This is a good example of how the ‘Request a copy’ service could be of direct benefit in the world outside academia.

Although the vast majority of requests have been for research outputs such as articles, theses and datasets, we also occasionally receive requests for images that belong to collections held in different parts of the University, where high-quality versions are stored in the repository under restricted access conditions. With these requests, it can be more difficult to find who the copyright-holder is, which sometimes requires detective work by the repository team. In one case, permission had to be sought from a photographer who only has a postal address, and therefore required more explanation about the repository more generally, as well as the specific request.

Looking to the future

We will use this research and any further feedback we receive to improve the experience of our ‘Request a copy’ service for both authors and requestors, including implementing the ideas suggested above. Usage statistics will continue to be monitored, and we may run a user survey again to determine how far the service has improved, as well as to identify any new issues.

In the meantime, if you have any comments or questions about our ‘Request a copy’ service, either as an author or a requester (or both), please send us an email to support@repository.cam.ac.uk .

The workshop, as mentioned, was very hands-on. By that I mean we did several ‘craft activities’ involving dots, glue, sticky tape and scissors. One of these activities involved ranking various tools for research against the four themes of the Principles, deciding whether they were in alignment with them (green), in opposition with them (red) or in-between (yellow).

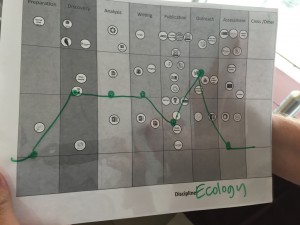

The workshop, as mentioned, was very hands-on. By that I mean we did several ‘craft activities’ involving dots, glue, sticky tape and scissors. One of these activities involved ranking various tools for research against the four themes of the Principles, deciding whether they were in alignment with them (green), in opposition with them (red) or in-between (yellow). We then placed these assessments on the windows under the part of the research lifecycle they related to, and ordered them. The most Principle-friendly tools were up high, and the least down low.

We then placed these assessments on the windows under the part of the research lifecycle they related to, and ordered them. The most Principle-friendly tools were up high, and the least down low. We then did an activity where we tried to trace the path of our own discipline in terms of the tools our disciplines tended to use. This exercise was an attempt to see if there were any discernable patterns about where some disciplines tend to align or otherwise with the Principles. While the sample size for each discipline was too small to really come to any conclusions, this exercise did open up ideas for a way of disseminating the Principles.

We then did an activity where we tried to trace the path of our own discipline in terms of the tools our disciplines tended to use. This exercise was an attempt to see if there were any discernable patterns about where some disciplines tend to align or otherwise with the Principles. While the sample size for each discipline was too small to really come to any conclusions, this exercise did open up ideas for a way of disseminating the Principles. The easiest part of the research lifecycle was to tackle was publishing, in terms of choosing a publication outlet. The decision tree allows for people who cannot publish in an Open Access journal, nor afford to pay for hybrid (not something I personally recommend anyway) to still be ‘Principled’ by putting a copy of their work in a repository.

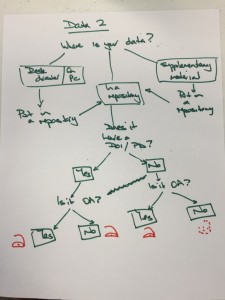

The easiest part of the research lifecycle was to tackle was publishing, in terms of choosing a publication outlet. The decision tree allows for people who cannot publish in an Open Access journal, nor afford to pay for hybrid (not something I personally recommend anyway) to still be ‘Principled’ by putting a copy of their work in a repository. Our discussion about data was more complex. For a start, there is a question about whether the data is digital or not. As we discussed it, our draft tree became incredibly complex so we created two separate flows. The Data 1 decision tree says to someone who has analogue data and no funds to digitise, that as long as they put in some information in their paper about how to contact them for the supporting data, then they have met the spirit of the Principles to the best of their ability.

Our discussion about data was more complex. For a start, there is a question about whether the data is digital or not. As we discussed it, our draft tree became incredibly complex so we created two separate flows. The Data 1 decision tree says to someone who has analogue data and no funds to digitise, that as long as they put in some information in their paper about how to contact them for the supporting data, then they have met the spirit of the Principles to the best of their ability. While we know the gold standard for data sharing is to have the data (with well defined metadata) available openly in a non proprietary repository with a DOI, for various reasons this is not always possible. We should not sanction a researcher because they are unable to meet that (very high) standard. The Data 2 tree shows that data that is in a repository under embargo without a DOI is discoverable in a way it would not be if it were in a desk drawer – so that is, again, within the spirit of the Principles. We need to consider the ‘close enough’ option as being a valid one, at least in the implementation stage of the Principles.

While we know the gold standard for data sharing is to have the data (with well defined metadata) available openly in a non proprietary repository with a DOI, for various reasons this is not always possible. We should not sanction a researcher because they are unable to meet that (very high) standard. The Data 2 tree shows that data that is in a repository under embargo without a DOI is discoverable in a way it would not be if it were in a desk drawer – so that is, again, within the spirit of the Principles. We need to consider the ‘close enough’ option as being a valid one, at least in the implementation stage of the Principles.