It only rains about 10 days a year in San Diego. And Tuesday was one of them. In a rooftop room on campus in San Diego at UCSD, a group had gathered for the FORCE11 Scholarly Commons workshop. The workshop brought together members of the Scholarly Commons working group, who hail from around the world and come from the broad scholarly commons. The Scholarly Commons is an idea to help define the future of research communication. The goal is to promote the best research and scholarship possible through rapid and wide dissemination to all who need or want it.

FORCE stands for the Future of Research Communications and eScholarship and is an organisation (or community) open to anyone interested in these issues. The group consisted of researchers from multiple disciplines, communicators, programmers, and a couple of librarians. This is the unusual and powerful thing about FORCE11 – the diversity of its members. Someone actually remarked: ‘you know, there probably should be a few more librarians here’ which is something you don’t often hear at meetings about open access issues. Usually librarians are delighted if a real live researcher turns up.

We were meeting to discuss the draft of 18 Principles of the Commons – an attempt to define what the community considers the attributes and behaviours of a person who is fully participating in research. The Principles are broadly separated into four major themes of being Open, Equitable, Sustainable and Research & Culture Driven.

FORCE11 works openly and tries to be as accessible as possible so there were full and open notes being collaboratively taken and the Twitter hashtag was #futurecommons.

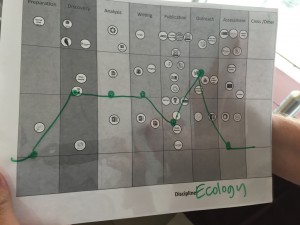

The workshop was very hands-on, and expertly moderated by Jeroen Bosman and Bianca Kramer who are the power behind the excellent 101 Innovations in Scholarly Communication project. As their ‘wheel’ of tools identifying tools available across the research life stages and through time demonstrates, it is becoming increasingly difficult to navigate the new research space. Indeed that is part of the rationale behind this Scholarly Commons project. It is an attempt to take stock and make sense of what we, the community, want to see in an open and accessible future.

Despite having fewer than 40 people we managed to have multiple activities running concurrently with several ‘unworkshops’. Everything was fed back into the group, and there was a very broad range of discussions, agreements and ideas. To prevent this blog being a tome, I am only going to cover here a couple of areas that were discussed.

Standing on the shoulders of giants

Due to a flight delay I was only able to catch the end of the Sunday evening welcome reception where we were asked to reflect on the 18 draft Principles plastered on the walls and decide which we agreed with and which we did not (or had an issue with). As I scanned through I was struck by the overall similarity they had with Robert Merton’s 1942 publication, The Normative Structure of Science where he proposed that science operated to four ‘norms’, of Universalism, Communalism, Disinterestedness and Organised Skepticism.

I mentioned this in an early discussion and was somewhat chuffed that the group really did take this on board – to the extent that one unworkshop group worked on updating the norms to reflect today’s situation.

I mentioned this in an early discussion and was somewhat chuffed that the group really did take this on board – to the extent that one unworkshop group worked on updating the norms to reflect today’s situation.

As an aside – the challenge with having people coming together from multiple research areas is everyone brings their a priori biases with them. People tend to see the problem through their own lens, so have different ways of approaching the problem. For the group to agree that this perspective was a good one was personally very validating.

Considering outreach as part of the research lifecycle

I the first unworkshop I joined we discussed how research-centred the Principles are – they did not consider the importance of outreach. Given the impenetrable nature of the language in many academic papers, we agreed that making something Open Access facilitates outreach but is not outreach itself.

The discussion moved to idea about what researchers could do to help with outreach – even if they themselves did not want (or were unable) to do it. These are fairly simple including providing supplementary material that is accessible in terms of the descriptive language used (no jargon), potentially providing the information in a different language to English, and ensuring the license under which it is made available is open.

We proposed that the Commons should facilitate outreach and have the outreach in mind even if the researcher themselves does not generate the outreach. There had been a comment earlier in the Equity discussion that noted “Each part of the research cycle is equally valid and none should not be preferenced over the other.” Our discussion concluded that outreach (for the lay public) should be considered to be part of the research process and equally valued.

It should be noted that we are not discussing paper-related activities here. Making the paper open access or tweeting a link to the paper doesn’t count. This is about sharing the information in an understandable manner outside the Academy.

Tool mapping

The workshop, as mentioned, was very hands-on. By that I mean we did several ‘craft activities’ involving dots, glue, sticky tape and scissors. One of these activities involved ranking various tools for research against the four themes of the Principles, deciding whether they were in alignment with them (green), in opposition with them (red) or in-between (yellow).

The workshop, as mentioned, was very hands-on. By that I mean we did several ‘craft activities’ involving dots, glue, sticky tape and scissors. One of these activities involved ranking various tools for research against the four themes of the Principles, deciding whether they were in alignment with them (green), in opposition with them (red) or in-between (yellow).

We then placed these assessments on the windows under the part of the research lifecycle they related to, and ordered them. The most Principle-friendly tools were up high, and the least down low.

We then placed these assessments on the windows under the part of the research lifecycle they related to, and ordered them. The most Principle-friendly tools were up high, and the least down low.

We then did an activity where we tried to trace the path of our own discipline in terms of the tools our disciplines tended to use. This exercise was an attempt to see if there were any discernable patterns about where some disciplines tend to align or otherwise with the Principles. While the sample size for each discipline was too small to really come to any conclusions, this exercise did open up ideas for a way of disseminating the Principles.

We then did an activity where we tried to trace the path of our own discipline in terms of the tools our disciplines tended to use. This exercise was an attempt to see if there were any discernable patterns about where some disciplines tend to align or otherwise with the Principles. While the sample size for each discipline was too small to really come to any conclusions, this exercise did open up ideas for a way of disseminating the Principles.

The Principles as an Innovation

This is where another of my disciplinary perspectives comes into play. If we accept that the Principles are themselves an ‘innovation’ – in that they are “an idea, practice, or object that is perceived as new by an individual or other unit of adoption”, then we can look to Everett Rogers Diffusion of Innovations first published in 1962, and now in its 5th edition. You might not have heard of him but you know about his work – Rogers was the person who coined the idea of ‘early adopters’, late adopters’ and ‘laggards’.

Amongst lots of interesting insights about why people adopt new ideas, Rogers came up with five ways to evaluate an innovation which will determine the success or otherwise of its adoption. These are judged as a whole and are interrelated:

- Relative advantage – the perceived efficiencies gained by the innovation relative to current tools or procedures

- Compatibility with the pre-existing system

- Complexity or difficulty to learn (it needs to be easy)

- Trialability or testability without risking the current system

- Observed effects.

It is the second point which is the interesting one here – ‘Compatibility with the pre-existing system’. The reason why this is relevant is we are not talking about one system when we discuss scholarship – there are a myriad of systems. There is no ‘one solution’. If we are to try and implement something like the Principles across the academy, we will need to do it along disciplinary lines. (Disclosure – this happens to be the conclusion of my 2008 PhD thesis on the adoption of open access across disciplines).

Disciplinary dissemination

This leads us to the question of audiences for the Principles. Ideally we would have institutions signing up to them, pledging that they will work with their research community to work in this manner. But this is unrealistic currently due to the diverse nature of research institutions. But there might be a way to have funders sign up, because often funding is given within disciplinary restraints. This is doubly the case because funders (in the UK, Australia and the US at least) are increasingly using an ‘Impact narrative’ and the Principles offer a way to practically identify and reward impact behaviour.

And we are not coming from a standing start. We can build on the work done by Jeroen Bosman and Bianca Kramer in their 101 Innovations in Scholarly Communication project. There were over 20,000 responses to their survey of innovation use and this allows a detailed mapping of disciplinary behaviours. If we the further map those findings against an assessment of the research tools being used at a disciplinary level and whether they are aligned with the Principles, we should be able to see which disciplinary areas are already working in the Principled way. It is the funders of these disciplines that we should approach first to try and gain early adoption of the Principles. This work would become a checklist that can reward people for the behaviours that they are already doing in this space.

A project like this would in turn open up some questions about what we need to do at a disciplinary level to help that community become more aligned with the Principles. These may require a number of approaches – Do they have the tools that work for them or do these need to be developed? Is there a cultural reason why this discipline is not engaging? In answering these questions we come up with the answer to the question: What does a Scholarly Commons researcher look like in this discipline? Until we have some evidence of where these areas are we are effectively stabbing in the dark.

Making this happen now

In a different unworkshop we talked about how the nature of the Principles themselves went against the idea of being inclusive because we are potentially creating a binary situation – either you are following the Principles or not. What we really need to do, we agreed, is not reject people for acting in ways that are not totally in line with the Principles, rather reward behaviour that supports the Principles.

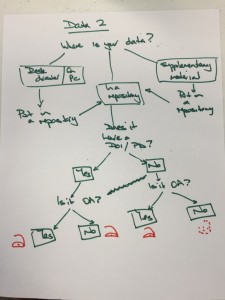

In order to facilitate this, we designed a series of ‘Decision Trees’ to help researchers be as open as they can. This is a recognition that researchers are working within a complex ecosystem. With all the will in the world, if there is not an Open Access journal available to you in your field, you cannot publish in one.

The easiest part of the research lifecycle was to tackle was publishing, in terms of choosing a publication outlet. The decision tree allows for people who cannot publish in an Open Access journal, nor afford to pay for hybrid (not something I personally recommend anyway) to still be ‘Principled’ by putting a copy of their work in a repository.

The easiest part of the research lifecycle was to tackle was publishing, in terms of choosing a publication outlet. The decision tree allows for people who cannot publish in an Open Access journal, nor afford to pay for hybrid (not something I personally recommend anyway) to still be ‘Principled’ by putting a copy of their work in a repository.

Our discussion about data was more complex. For a start, there is a question about whether the data is digital or not. As we discussed it, our draft tree became incredibly complex so we created two separate flows. The Data 1 decision tree says to someone who has analogue data and no funds to digitise, that as long as they put in some information in their paper about how to contact them for the supporting data, then they have met the spirit of the Principles to the best of their ability.

Our discussion about data was more complex. For a start, there is a question about whether the data is digital or not. As we discussed it, our draft tree became incredibly complex so we created two separate flows. The Data 1 decision tree says to someone who has analogue data and no funds to digitise, that as long as they put in some information in their paper about how to contact them for the supporting data, then they have met the spirit of the Principles to the best of their ability.

While we know the gold standard for data sharing is to have the data (with well defined metadata) available openly in a non proprietary repository with a DOI, for various reasons this is not always possible. We should not sanction a researcher because they are unable to meet that (very high) standard. The Data 2 tree shows that data that is in a repository under embargo without a DOI is discoverable in a way it would not be if it were in a desk drawer – so that is, again, within the spirit of the Principles. We need to consider the ‘close enough’ option as being a valid one, at least in the implementation stage of the Principles.

While we know the gold standard for data sharing is to have the data (with well defined metadata) available openly in a non proprietary repository with a DOI, for various reasons this is not always possible. We should not sanction a researcher because they are unable to meet that (very high) standard. The Data 2 tree shows that data that is in a repository under embargo without a DOI is discoverable in a way it would not be if it were in a desk drawer – so that is, again, within the spirit of the Principles. We need to consider the ‘close enough’ option as being a valid one, at least in the implementation stage of the Principles.

We agreed that in some areas of the research lifecycle that a list of tools that could help would be of more use than a decision tree. Time restraints meant there are a couple of areas of the lifecycle which still need consideration (and we need to do some decision tree design work!), but generally the group agreed that this was probably quite useful.

Conclusions

When it comes to the Principles themselves, we are still working on it. We did however agree that we thought the Principles were something worth doing, and that they were more or less something we can start working with (and on – they are likely to be dynamic). One suggestion was that we call them Scholarly Commons Principles 1.0 – a reference to this being the first version of possibly many. There are plans for several subgroups to pitch for funding to do some deeper work in some areas. So it is an ongoing project, but a substantial one.

There are some troopers in the Scholarly Communication community. Several people at our workshop had ‘done the double’ – attending the SciDataCon 2016 conference and associated meetings over eight days in Denver last week and then coming to this event. The gruelling pace was starting to show by the end of the last day of our workshop.

You know you have been on a very short visit when you fly back with the same in-flight crew as your outward bound journey. One of them even recognised me and commented on how quickly I was returning. So while the trip was an exhausting few days, it was productive and worthwhile. And it was really nice to smell eucalypt trees (rather bizarrely) and do laps in an outdoor pool – things I have not done since moving to the UK.

You know you have been on a very short visit when you fly back with the same in-flight crew as your outward bound journey. One of them even recognised me and commented on how quickly I was returning. So while the trip was an exhausting few days, it was productive and worthwhile. And it was really nice to smell eucalypt trees (rather bizarrely) and do laps in an outdoor pool – things I have not done since moving to the UK.