Last week, the Research Data Team at the Office of Scholarly Communication recorded the inaugural Data Diversity Podcast with Data Champion Danny van der Haven from the Department of Material Science and Metallurgy.

As is the theme of the podcast, we spoke to Danny about his relationship with data and learned from his experiences as a researcher. The conversation also touched on the differences between lab research and working with human participants, his views on objectivity in scientific research, and how unexpected findings can shed light on datasets that were previously insignificant. We also learn about Danny’s current PhD research studying the properties of pharmaceutical powders to enhance the production of medication tablets.

Click here to listen to the full conversation.

If you have heart rate data, you do not want to get a different diagnosis if you go to a different doctor. Ideally, you would get the same diagnosis with every doctor, so the operator or the doctor should not matter, but only the data should matter.

– Danny van der Haven

***

What is data to you?

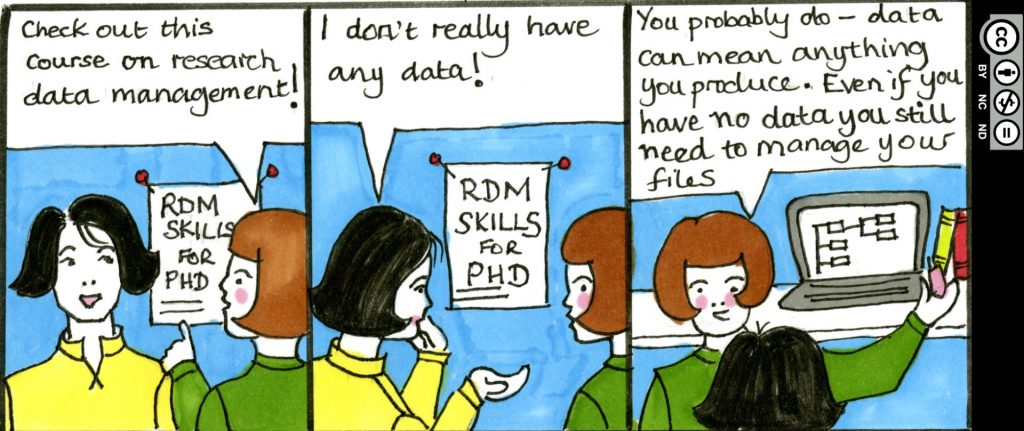

Danny: I think I’m going to go for a very general description. I think that you have data as soon as you record something in any way. If it’s a computer signal or if it’s something written down in your lab notebook, I think that is already data. So, it can be useless data, it can be useful data, it can be personal data, it can be sensitive data, it can be data that’s not sensitive, but I would consider any recording of any kind already data. The experimental protocol that you’re trying to draft? I think that’s already data.

If you’re measuring something, I don’t think it’s necessarily data when you’re measuring it. I think it becomes data only when it is recorded. That’s how I would look at it. Because that’s when you have to start thinking about the typical things that you need to consider when dealing with regular data, sensitive data or proprietary data etc.

When you’re talking about sensitive data, I would say that any data or information of which the public disclosure or dissemination may be undesirable for any given reason. That’s really when I start to draw the distinction between data and sensitive data. That’s more my personal view on it, but there’s also definitely a legal or regulatory view. Looking for example at the ECG, the electrocardiogram, you can take the electrical signal from one of the 12 stickers on a person’s body. I think there is practically nobody that’s going to call that single electrical signal personal data or health data, and most doctors wouldn’t bat an eye.

But if you would take, for example, the heart rate per minute that follows from the full ECG, then it becomes not only personal data but also becomes health data, because then it starts to say something about your physiological state, your biology, your body. So there’s a transition here that is not very obvious. Because I would say that heart rate is obviously health data and the electrical signal from one single sticker is quite obviously not health data. But where is the change? Because what if I have the electrical signal from all 12 stickers? Then I can calculate the heart rate from the signal of all the 12 stickers. In this case, I would start labelling this as health data already. But even then, before it becomes health data, you also need to know where the stickers are on the body.

So when is it health data? I would say that somebody with decent technical knowledge, if they know where the stickers are, can already compute the heart rate. So then it becomes health data, even if it’s even if it’s not on the surface. A similar point is when metadata becomes real data. For example, your computer always saves that date and time you modified files. But sometimes, if you have sensitive systems or you have people making appointments, even such simple metadata can actually become sensitive data.

On working within the constraints of GDPR

Danny: We struggled with that because with our startup Ares Analytics, we also ran into the issues with GDPR. In the Netherlands at the time, GDPR was interpreted really stringently by the Dutch government. Data was not anonymous if you could, in any way, no matter how difficult, retrace the data to the person. Some people are not seeing these possibilities, but just to take it really far: if I would be a hacker with infinite resources, I could say I’m going to hack into the dataset and see the moments that the data that were recorded. And then I can hack into the calendar of everybody whose GPS signal was at the hospital on this day, and then I can probably find out who at that time was taking the test… I mean is that reasonable? Is anybody ever going do that? If you put those limitations on data because that is a very, very remote possibility; is that fair or are you going hinder research too much? I understand the cautionary principle in this case, but it ends up being a struggle for us in in that sense.

Lutfi: Conceivably, data will lose its value. If you really go to the full extent on how to anonymise something, then you will be dataless really because the only true way to anonymise and to protect the individual is to delete the data.

Danny: You can’t. You’re legally not allowed to because you need to know what data was recorded with certain participants. Because if some accident happens to this person five years later, and you had a trial with this person, you need to know if your study had something to do with that accident. This is obvious when you you’re testing drugs. So in that sense, the hospital must have a non-anonymised copy, they must. But if they have a non-anonymized copy and I have an anonymised copy… If you overlay your data sets, you can trace back the identity. So, this is of course where you end up with a with a deadlock.

What is your relationship to data?

Danny: I see my relationship to data more as a role that I play with respect to the data, and I have many roles that I cycle through. I’m the data generator in the lab. Then at some point, I’m the data processor when I’m working on it, and then I am the data manager when I’m storing it and when I’m trying to make my datasets Open Access. To me, that varies, and it seems more like a functional role. All my research depends on the data.

Lutfi: Does the data itself start to be more or less humanised along the way, or do you always see it as you’re working on someone, a living, breathing human being, or does that only happen toward the end of that spectrum?

Danny: Well, I think I’m very have the stereotypical scientist mindset in that way. To me, when I’m working on it, in the moment, I guess it’s just numbers to me. When I am working on the data and it eventually turns into personal and health data, then I also become the data safe guarder or protector. And I definitely do feel that responsibility, but I am also trying to avoid bias. I try not to make a personal connection with the data in any sense. When dealing with people and human data, data can be very noisy. To control tests properly, you would like to be double blind. You would like not to know who did a certain test, you would like not to know the answer beforehand, more or less, as in who’s more fit or less fit. But sometimes you’re the same person as the person who collected the data, and you actually cannot avoid knowing that. But there are ways that you can trick yourself to avoid that. For example, you can label the data in certain clever way and you make sure that the labelling is only something that you see afterwards.

Even in very dry physical lab data, for example microscopy of my powders, the person recording it can introduce a significant bias because of how they tap the microscopy slide when there’s powder on it. Now, suddenly, I’m making an image of two particles that are touching instead of two separate particles. I think it’s also kind of my duty, that when I do research, to make the data, how I acquire it, and how it’s processed to be as independent of the user as possible. Because otherwise user variation is going to overlap with my results and that’s not something I want, because I want to look at the science itself, not who did the science.

Lutfi: In a sentence, in terms of the sort of accuracy needed for your research, the more dehumanised the data is, the more accurate the data so to speak.

Danny: I don’t like the phrasing of the word “dehumanised”. I guess I would say that maybe we should be talking about not having person-specific or operator-specific data. If you have heart rate data, you do not want to get a different diagnosis if you go to a different doctor. Ideally, you would get the same diagnosis with every doctor, so the operator or the doctor should not matter, but only the data should matter.

***

If you would like to be a guest on the Data Diversity Podcast and have some interesting data related stories to share, please get in touch with us at info@data.cam.ac.uk and state your interest. We look forward to hearing from you!