On Friday 27 November Danny Kingsley attended the SCONUL Winter Conference 2015 which addressed the theme of disruptive innovation and looked at the changes in policy and practice which will shape the scholarly communications environment for years to come. This blog is a summary of her notes from the event. The hastag was #sconul15 and there is a link in Twitter.

Disruptions in scholarly publishing

Dr Koen Becking, President of the Executive Board, Tilburg University, spoke first. He is the lead negotiator with the publishers in the Netherlands. Things are getting tight as we count down to the end of the year given the Dutch negotiations with Elsevier (read more in ‘Dutch boycott of Elsevier – a game changer?‘)

Koen asked: what is the role of a university – is it knowledge to an end, knowledge in relation to learning or knowledge in relation to professional skills? He said that 21st century universities should face society. While Tilburg University is still tied to traditional roots, it is now focused in the idea of ‘third generation university’. The idea of impact on society – the work needs to impact on society.

The Dutch are leading on the open access fight and Koen said they may look at legislation to force the government goal of open access to research articles of 40% by 2016 & 100% by 2024. [Note that the largest Dutch funder NOW has just changed their policy to say funds can no longer be used to pay for hybrid OA and that green OA must be available ‘the moment of’ publication].

Kurt noted that the way the Vice Chancellors got involved in the publisher discussions in the Netherlands was the library director came to him ask about increasing the subscription budget and the he asked why it was going up so much given the publisher’s profit levels. Money talks.

Managing the move away from historic print spend

Liam Earney from Jisc said there were several drivers for the move from historic print spend and we need models that are transparent, equitable, sustainable and acceptable to institutions. They have been running a survey on acceptable metrics on cost allocation (note that Cambridge has participated in this process). Jisc will shortly launch a consultation document on institutions on new proposals.

Liam noted that part of their research found that it was apparent that across Jisc bands and within Jisc bands there are profound differences in what institutions paying for the same material – sometimes by a factor of 100’s of 1000’s pounds different to access the same content in similar institutions.

They also worked out that if they took a mix of historical print spend and a new metric it would take over 50 years to migrate to a new model. This is not realistic.

Jisc is supported by an expert group of senior librarians (including members at Cambridge) who are working on an alternative. Liam noted that historical print spend is harmful to the ability of a consortium to negotiate coherently. Any new solution needs to meet the needs of academics and institutions.

Building a library monograph collection: time for the next paradigm shift?

Diane Brusvoort from the University of Aberdeen comes from the US originally and talked about collaborative collection development – we can move together. Her main argument was that for years we have built libraries on a ‘just in case model’ and we can no longer afford to do that. We need to refine our ‘just in time’ purchasing to take care of faculty requests, also have another strand working across sector to develop the ‘for the ages’ library.

She mentioned the FLorida Academic REpository (FLARE) which is the statewide shared collection of low use print materials from academic libraries in Florida. Libraries look at what is in FLARE and move the FLARE holding into their cataloguing. It is a one copy repository for low use monographs. The Digital Public Library of America is open to anything that had digitised content can be put in the DPA portal and deals with the problem of items that they are all siloed.

Libraries are also taking books off the shelf when there is an electronic version. This is a pragmatic decision not made because lots of people are reading the electronic one preferentially, it is simply to save shelf space.

Diane noted a benefit of UK compared to UK is the size – it is possible to do collaborative work here in ways you can’t in the US. We need collaborative storage and to create more opportunities for collaborative collections development.

The Metric Tide

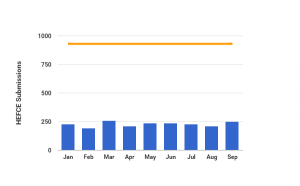

Professor James Wilsdon – University of Sussex spoke about the HEFCE report he contributed to The Metric Tide: Report of the Independent Review of the Role of Metrics in Research Assessment and Management.

This report looked at responsible uses of quantitative data in research management and assessment. He said we should not turn our backs on big data and its possibilities but we know of our experience in the research systems that these can be used as blunt tools in the process. He felt that across the community at large the discussion about metrics was unhelpfully polarised. The debate is open to misunderstanding and need a more sophisticated understanding on ways they can be used more responsibly.

The agreement is that peer review is the ‘least worst’ form of academic governance that we have. Metrics should support not supplant academic management. This underpins the design of assessment exercises like the REF.

James noted that the metrics review team was getting back together that afternoon to discuss ‘section d’ in the report. He referred to this as being ‘like a band reunion’.

A new era for library publishing? The potential for collaboration amongst new university presses

This workshop was presented by Sue White, Director of Computing and Library Services and Graham Stone, Information Resources Manager, University of Huddersfield.

Sue talked about the Northern Collaboration of libraries looking at joining forces to create a publishing group. They started with a meeting in October 2104. There is a lot of uncertainty in the landscape, with a big range of activity from well established university presses to those doing no publishing at all. She said the key challenges to the idea of a joint press was the competition between institutions. But they decided the idea merited further exploration.

Discussions were around the national monograph strategy roadmap that advocated university publishing models. The Northern Collaboration took a discussion paper to Jisc – and they suggested three areas of activity. They were:

- Benchmarking and data gathering to see what was happening in the UK.

- Second to identify best practice and possible workflow efficiencies- common ground.

- Third was exploring potential for the library publishing coalition.

The project is about sharing and providing networks for publishing ventures. In the past couple of days Jisc has agreed to take the first two forward and welcome input. They want some feedback about taking it forward.

Graham then spoke about the Huddersfield University Press which has been around since 2007 – but was re-launched with an open access flavour. They have been publishing open access materials stuff for three to four years. They publish three formats – monographs, journal publications and sound recordings.

The principles governing the Press is that everything is peer reviewed, as a general rule everything should be open access and they publish by the (ePrints) open access repository which gets lots of downloads. The Press is managed by the library but led by the academics. Business model is a not for profit as it is scholarly communication. If there were any surplus it would be reinvested in the Press. In last four years they have published 12 monographs, of which six are open access.

Potential authors have to come with their own funding. Tends to be an institutional funder sponsored arrangement. The proposal form has a question ‘how is this going to be funded’? This point is ignored for the peer review process. Having money does not guarantee publishing. It means it will be looked at but doesn’t guarantee publishing. The money pays for a small print run, copy editing not staff costs. About a 70,000 word monograph costs in the region of £3000-£4000.

Seven journals are published in the repository – there is an overlay on the repository, preserved in Portico. Discoverable through Google (via OAI-PMH) compliance with repository, Library webscale discovery includes membership of the DOAJ. Their ‘Teaching and lifelong learning’ journal has every tickbox on DOAJ.

The enablers for this Press have been senior support in the university at DVC level and the capacity and enthusiasm of an Information Resource Manager to absorb the Press into existing role. Also having an editorial board with people across the institution. The Press is operating on a shoestring hard. It is difficult to establish reputation and convincing the potential stakeholders and impact. A lack of long term funding means it is difficult to forward plan.

They also noted that there are not very many professional support networks out there and it would be good to have one. They need specialist help with author contracts and licences.

Who will disrupt the disruptors?

The last talk was by Martin Eve, Senior Lecturer in Literature, Technology and Publishing, Birkbeck, University of London. This was an extremely entertaining and thought provoking talk. The slides are available.

Martin started with critical remarks about the terminology of ‘disruptive’, arguing that often the word is used so the public monopoly can be broken up into private hands. That said, there are parts of the higher education sector which are broken and need disruption.

Disruption is an old word – from Latin used first in 15th century. Now it actually means the point at which an entire industry is shifted out. What we see now is just a series of small increments. The changes happening in the higher education sector are not technological they are social and it is difficult to break that cycle of authority and how it works.

Martin argued that libraries need to be strategic and pragmatic. We have had a century long breakdown of the artificial scarcities in trading of knowledge coming to a head in the digital age. There are new computational practices with no physical or historical analogy – the practices don’t fit well with current understandings. He gave a couple of historical examples where in the 1930s people made similar claims.

The book as a product of scholarly communication is so fetishized that when we want the information we need the real object – we cannot conceive of it in another form.

Universities in the digital age just don’t look like they did before. We have an increasingly educated populace – more people can actually read this stuff so the argument that ‘the public’ can’t understand it is elitist and untrue. Institutional missions need to be to benefit society.

Martin discussed the issues with the academic publication market. A reader always needs a particular article – the traditional discourses around the market play out badly. You don’t know if you need a particular article until you read it and if you do need it you can’t replace it with anything else.

Certain publications can have a rigorous review practice because they are receiving high quality submissions. But they only get high quality submissions if you have lots of them and they get that reputation because of a rigorous review practice. So early players have the advantage.

He noted that different actors care about the academic market in different ways. Researchers produce academic products for themselves – to buy an income and promotion. Publishers frame their services as doing things for authors – but they don’t do enough for readers and libraries. Who pays? Researchers have zero price sensitivity. Libraries are stuck between rock & hard place. They have the cash but are told how to spend it. The whole thing is completely dysfunctional as a market. In the academy, reading is underprivileged. Authorship is rewarded.

Martin then talked about open access and how it affects the Humanities. He noted that monographs are acknowledged as different – eg: HEFCE mandate. There are higher barriers for entry to new publishers – people don’t have a good second book to give away to an OA publisher. There are different employment practices, for example creative writers are often employed on a 0.5 contract – they are writing novels and selling them and commercial publishers get antsy about requirements for open access because there is a cross over with trade books.

The subscription model exists on the principle that if enough people contribute then you have enough centrally to pay for what the costs are. It assumes a rivalrous mode – the assumption is there will always be greedy people who won’t pay in if they don’t get an exclusive benefit.

The Open Library of the Humanities is funded by a library consortium. It is based on arXiv funding model and Knowledge Unlatched. Libraries pay into a central fund in the same way of a subscription. Researcher who publish with us do not have to be at an institution who is funding or even at an institution. There are 128 libraries financially supporting the model (as of Monday should be 150). The rates are very low – each one only has to pay about $5 per article. They are publishing approximately 150 articles per year.