As part of the Office of Scholarly Communication Open Access Week celebrations, we are uploading a blog a day written by members of the team. Thursday is a piece by Dr Arthur Smith looking to the future.

Introduction

Academic publishing is not what it used to be. Open access has exploded on the scene and challenged the established publishing model that has remained largely unchanged for 350 years. However, for those of us working in scholarly communications, the pace of change feels at times frustratingly slow, with constant roadblocks along the way. Navigating the policy landscape provided by universities, funders and publishers can be maddening, yet we need to remain mindful of how far we have come in a relatively short time. There is no sign that open access is losing momentum, so it’s perhaps instructive to consider the direction we want open access to take over the next five years, based upon the experiences of the past.

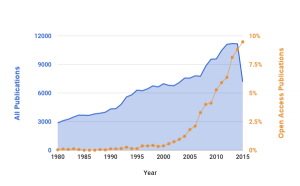

So how much is the University of Cambridge publishing and is it open access? Since 1980, according to Web of Science, the University’s publications increased from 3000 articles per year to more than 11,000 in 2014 (Fig. 1). Over the same period the proportion of gold open access articles rose steadily since first appearing on the scene in the late 1990s. Thus far in 2015 nearly one in ten articles is available gold open access, although this ignores the many articles available via green routes.

Fig. 1. Publications at the University of Cambridge since 1980 according to WoS (accessed 14/10/2015).

The HEFCE policy

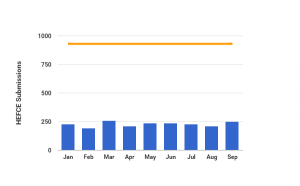

By far the most important development for open access in the UK has been the introduction of HEFCE’s open access policy. As the policy applies to all higher education institutions it affects every university researcher in the UK. While the policy doesn’t formally start until April 2016, so far progress has been slow (Fig. 2). We believe that less than a third of all the University’s articles that are published today are currently compliant with the HEFCE policy, and despite a strong information campaign, our article submission rate has stagnated at around 250 articles per month, well off the monthly target of 930.

Fig. 2. Publications received to the University of Cambridge open access service. The target number of articles per month is 930.

It’s understandable that some papers will fall through the cracks, but even for high impact journals many papers still don’t comply with the policy. But let’s be clear, aside from any policy compliance issues and future REF eligibility, these numbers reveal that fully two thirds of research papers produced at the University cannot be read without a journal subscription. And if readers can’t afford to pay for access then they’ll happily find other means of obtaining research papers.

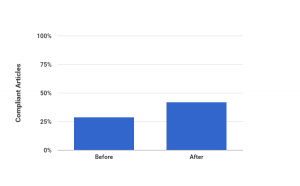

What about inviting authors to make their research papers open access? Since June I have tracked five high impact journals and monitored the papers published by University of Cambridge authors (Fig. 3). Upon first discovery of a published paper, only 29% of articles were compliant with the HEFCE policy, which is consistent with our overall experience in receiving AAMs. But even after inviting authors to submit their accepted manuscripts to the University’s open access repository, the number of compliant articles rose to only 42%. Less than a third of authors who were directly contacted and asked to make their work open access eventually submitted their manuscripts. Clearly, the merits of open access are not enough to convince authors to act and distribute their manuscripts.

Fig. 3. Compliant articles published in five high impact journals. Even after direct intervention less than half of all articles are HEFCE compliant.

SCOAP³

The SCOAP3 initiative is a publishing partnership that makes journals in the field of particle physics open access. This innovative scheme brings together multiple universities, funders and publishers and turns traditional journals, that are already widely respected by the physics community, into purely open access journals. No intervention is required by either authors or university administrators, making the process of publishing open access as simple as possible. The great advantage of this scheme is that authors don’t need to worry about choosing an open access option from the publisher, nor deal with messy invoices or copyright issues. All of these problems have been swept away.

Jisc Springer Compact

Like SCOAP3 the recently announced Jisc Springer Compact is a coalition of universities in the UK that have agreed a publishing model with Springer that makes ~1600 journals open access. Following a similar Dutch agreement, this publishing model means that any authors with qualifying institutional affiliations will have their publications made open access automatically. We’ve already started receiving our first requests under this scheme. However, unlike the SCOAP3 initiative which ‘flips’ entire journals to gold OA, the journals under the UK Jisc Springer Compact are still hybrid and only content produced by qualifying authors is open access. While this is great for those universities signed up to the deal, it still leaves a great many papers languishing under the subscription model.

Affiliation vs. Community

So which of these strategies will prove to the most successful? Will universities take ownership of open access publishing or will subject based communities come together in publishing coalitions.

The advantage of subject based initiatives is they flip entire journals for the benefit of a whole research community, making all the work within a specific discipline open access. However, without sufficient cohesion and drive within an academic community it’s likely that adoption will be fragmented across the myriad of disciplines. It’s no surprise that SCOAP3 emerged out of the particle physics community, given this scholarly community’s involvement in the development of arXiv, but it’s unrealistic to expect this will be the case everywhere.

Publishing agreements based around institutional affiliations will undoubtedly become more common, but until all universities have agreements in place with all the major publishers (Elsevier, Wiley, Springer, etc.) then a large fraction of scholarly outputs will still remain locked down.

What does the future hold?

Ultimately I want to do myself out of a job. As odd as that sounds, the current system of paying publishers for individual papers to be made open access is a laborious and time consuming process for authors, publishers and universities. Similarly the process of making accepted manuscripts available under the green model is equally ridiculous. Publishers should be automatically depositing AAMs on behalf of authors. There is no evidence that making AAMs available has ever killed a journal, and besides, the sooner we can reach agreements with all the major publishers and research funders that result in change on a global scale the better it will be for everyone.