Open access book formats have been under discussion for several years and have attracted interest – and concern – from researchers in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences as well as amongst institutions, publishers, and funders. Earlier this month the Office of Scholarly Communication organised a one-day symposium on ‘Open Access monographs: from policy to reality’ which took place at St Catharine’s College, Cambridge. It aimed to enable discussion about the open access monographs agenda and its future challenges with the Cambridge community and beyond, to bring together researchers with publishers, funders, experts and innovators in the field of open monograph publishing, and to share experiences about the opportunities and realities of publishing an open access book.

In this blog we summarise the key themes that emerged from this symposium. In favour of simplicity we accept that many of the issues discussed do not belong to one theme category only and are interlinked with each other.

‘What would it take to implement open access books for REF?’

This was one of the first questions in Prof Martin Paul Eve’s (Birkbeck, University of London) keynote speech which highlights an uncomfortable truth in the discussions about open access monograph policy in the UK these days.

‘To publish 75% of anticipated monographic submission output for the next REF would require approximately £96m investment over the census period. This is equivalent to £19.2m per year. Academic library budgets as they are currently apportioned would not support this cost.’ [1]

The figures are staggering and immediately show that money is the number one challenge in any discussions about monographs in this context. Which brings us swiftly to our first theme: The economics of open access.

The economics of open access

The distribution of the economics is the most important factor in the puzzle of open access monograph publishing. The overall consensus from both publishers and academics are that BPCs (Book Publishing Charges) for monographs do not work well in the humanities. They scale badly and concentrate costs. However, it is clear that one business model does not fit all in this sphere. A diversity of business models and ecosystems in which monographs can be published as open access would give authors choice and avoid monopolies. It was thought provoking to hear Rupert Gatti say that Open Book Publishers couldn’t scale up on their current business model to publish 250-300 books (10 times the amount they do now) but they shouldn’t have to. Instead, they can envisage a system where numerous small publishers like themselves exist next to large publishers, like Cambridge University Press (CUP). The idea of avoiding monopolies is not only key for authors but also readers as having a few publishers controlling the methods of distribution of this literature could end up restricting the way we access and use content.

Questions were also raised about how BPCs (or their replacement) should be set. Monographs vary in length and complexity, usually determined by their subject matter, which in turn have vastly different production costs. Should there then be a pricing structure that better reflects this? And in a culture of openness, can we ask publishers to be transparent about their costs and services so researchers can make more informed choices about where to spend their grant money?

Publishers are very aware of the impact that open access is having on the business models and the need to maintain quality in production and the peer review process. CUP stated that digital sales are becoming an important part of monograph publishing and that timing of open access is also quite an important factor in the economics. Exploring models of delayed open access might provide one solution to protecting publisher incomes whilst still opening up access to content.

‘Students cannot learn without images’ (Dr Nicky Kozicharow, University of Cambridge)

Another important piece of the puzzle is who pays for the costs of publishing an open access book? The current model used for STEMM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics and Medicine) journal article APCs (Article Processing Charges), where funders usually pay the costs, was referred to an epistemic injustice that should not be replicated as researchers in less economically developed countries are disadvantaged.

The problem around costs of reproducing third-party images was also widely discussed, especially by Dr Nicky Kozicharow. Not enough is being done to support researchers, such as art historians, who rely on images for teaching and research activities. There is a (perceived) lack of training in copyright, which was a useful message, if not an uncomfortable one, to our librarians who routinely deliver training in this and are now revisiting their communications about this. But also image holders should consider how they support researchers – whilst some big holders, such as The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Wellcome Trust, the Getty Collection and Wikimedia, do provide images free of charge, there was the suggestion that other collection holders should consider opening up access for researchers at affiliated institutions. This access would need to continue for a number of years beyond that affiliation so the images are accessible during the period in which a book will often be written up.

Ethics, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion

“Who and what is OA for? We need to start with the right question” (Prof Margot Finn, President of the Royal Historical Society)

It is also important to view the economic question of who can afford to pay to publish an open access monograph through the lens of equality and inclusion. How can we ensure everyone has equal access to the opportunity to publish open access? Is open access a human right? The role of politics here is critical if we want to make open access work for everyone. Policymakers need to consider issues such as access, gender and nationality when making decisions that institutions and publishers have to interpret and adhere to.

Another group that suffers from the current set up for open access monographs are the early career researchers (ECRs). They often work in a precarious situation, moving between institutions on short term contracts. This restricts their ability to publish a monograph, which takes considerable time and effort. It is important that when institutions look to sign up to and implement statements such as DORA (San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment), that both monographs and journal articles are considered when looking at academic career progression.

Of course, as we strive to make open access work for everyone, we need to be mindful of impinging on academic freedoms. As noted by Dr Steven Hill (Director of Research, Research England), researchers should still be free to choose the questions they study within the constraints of the system. Academics should also be free to choose the licence that they publish their work under. This has been a major sticking point for many academics (as we have previously written) with CC BY licences seen as an ethical issue in the humanities. Instead, what is needed is a softening of licence choices with options such as non-commercial and non-derivative available – a point also highlighted in the recent Universities UK report on ’Open Access and Monographs’. Finally, we should not make assumptions that the ethical issues around licenses are the same worldwide, because they are not.

Scalability and sustainability

‘We need to understand fully the obstacles that underpin academic research in order to have a sustainable, scalable, global open access model – but we are not there’ (Prof Margot Finn, President of the Royal Historical Society)

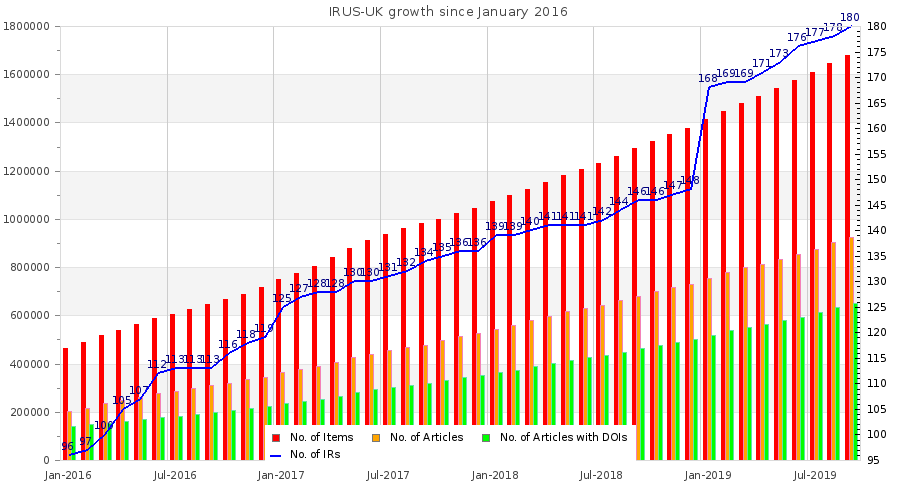

The issues around open access monographs are, at times, inextricably linked. Problems to do with economics are inseparable from issues of fairness (to sum the above section up badly) but also in scalability and sustainability. The academic monograph has its own distinct ecosystem in scholarly research. Open access monographs have a global readership, but production of open access books is not necessarily global, but concentrated on local or national levels. We need to consider the far-reaching consequences of this, including the relationship between the ‘global’ academic researcher and the ‘local’ publisher. We must also consider the role of the policymakers, often European, who set the rules in one country or part of the world and those academics who are not part of this system. Do the levels of academics in these countries and their outputs justify this dominance? We should also obtain more information on how open access books are used in order to justify the expenditure in publishing them, yet Hannah Hope, speaking for the Wellcome Trust, commented that the impact of open access books is hard to measure. Download statistics are often available and provide one measure. For example, UCL Press have had 2.5 million book downloads since its launch four years ago and Open Book Publishers report that their books are being freely accessed worldwide by over 20,000 readers each month.

The ability of publishers to innovate is seen as a key factor in the sustainability and scalability of open access monograph publishing. The size of the publisher will most probably determine their ability to innovate, with smaller publishers being in a better position to ‘take risks’ and try out new models, even if such models end up failing or not being appropriate to implement in bigger organisations due to scalability and financial constraints. Radical OA are experimenting with various business models and bringing down BPCs. The RHS’s New Historical Perspectives (NHP) book series is designed to provide high-quality publishing support to ECR historians (ECRs defined as researchers within 10 years of finishing their PhD) whilst absorbing the costs of BPCs and relying on a generous donation to cover some of the image costs. Indeed, ‘Learned societies have a long history of innovation and experimentation in publishing’ according to Prof Margot Finn, but how they take their experimentation to the next level is yet to be figured out.

Understanding how open access monographs can scale and be sustainable is key to figuring out the type of open access that will prevail. Green open access is not considered to be the future goal for CUP, who are experimenting with a number of different business models such as consortium models, crowdfunding and freemium models. They have also been engaging with authors, researchers and librarians worldwide to understand the monograph landscape better and to demystify issues concerning publishing process. Likewise, SpringerNature voiced concerns with green open access and although open access humanities publications account for a very small proportion of their overall open access publications (~10%) they feel that they are well positioned for a more open future.

Collaboration, relationships, communication

‘Publishing is not the end point. Academy as a whole needs to engage with that’ (Dr Rupert Gatti Trinity College/Faculty of Economics/Open Book Publishers)

What is clear is that there are many players in the field of open access monograph publishing and continued and open communication between all parties is key. Within institutions, academics and research support providers (such as librarians) need to have conversations to ensure the help required is accessible, so authors are not battling with copyright issues alone or remain unaware of the full spectrum of publishing options available to them. Senior leaders at universities must engage with their academic communities to understand the issues they face. They can then in turn engage with policymakers to encourage realistic rules and guidance that would lead to meaningful, measurable outcomes. It was reassuring to hear that consultative approaches are being taken and we welcome the continuation of these.

Publishers also have an important role in re-defining their relationship with academics. As Prof Martin Paul Eve questioned, are publishers solely service providers and academics content creators or are both parties co-producers and academic collaborators in the research process? Prof Roger Kain emphasised ‘the relationship of an author with their publisher with a journal is a very different relationship to the relationship of an author and their publisher with a monograph’ and as such this may lead to the chance to experiment further with business models, if publishers offer more added value through intellectual support for their authors. Of course, Learned Societies and holders of large collections of images have to be involved as well so that their position within the research process is well understood. These conversations should also happen in and between different geographical places because academic research will always have international collaborations.

We also have to be mindful of the messages that come out of these conversations. Time and again we heard the notion that “open access means bad peer review” is still alive in the academic community. This is a myth that all publishers, as well as librarians and other research support staff, are keen to debunk. Another myth is the misconception that “open access is the end of print”. As Prof Roger Kain put it ‘open access does not mean wholly replacing the physical copies of a book but help creators of content to reach wider audiences…OA and print will co-exist’. The term “open science” was noted as appearing to exclude the humanities and, therefore, disengaging researchers before they’ve even got started, even though open science includes all disciplines (this is the reason why in Cambridge we prefer to use “open research”). The language used in Plan S communication was seen as being too opaque, especially for non-native English speakers. If we are encouraging open research, we should be using language that is open and transparent, especially when open research is an international endeavour, as already mentioned. It is important that messages are correct and clear so humanities scholars and other stakeholders can engage fully in debates about the future of open access monograph publishing.

Summary

‘If we are going to take open access for monographs forward in a timely fashion it has to be taken forward as a shared enterprise…an enterprise involving academics as content creators, their funders, their universities…but above all their publishers’ (Prof Roger Kain, School of Advanced Study, University of London & Chairman of the UUK OA Monographs Group)

The symposium saw common themes emerging around issues with open access for monographs as the system currently stands, but also the potential benefits and possibilities that open access could open up into the future. There was consensus that open access needs to go forward as a shared enterprise with all stakeholders being equal players. Looking into the future there was also concern about the visibility of humanities research going forward when compared to the natural sciences and that humanities authors should strive to demonstrate the impact of their publishing activities.

Many of the themes discussed in this symposium echoed the recommendations as well as concerns outlined in the Universities UK Open Access Monograph report which was published a few days after this symposium took place. The report emphasised that complex questions still remained around issues such as costs, scalability and business models, but it was positive to read statements that the ‘academic book occupies a very distinct space in scholarly research’ reinforcing the fact that monographs are fundamentally different in intention and in kind when compared with journals or fields of research, and that ‘academic book publishing is an international activity’, with whatever implications this entails, as discussed earlier.

Perhaps it is fitting to conclude with a dose of pragmatism by quoting one of Dr Steven Hill’s remarks at the end of the symposium

‘...a really strong dose of pragmatism has entered this debate; that we all recognise that there are different visions of utopia that different actors in the system might have, but we can see that some of our visions of utopia have to be compromised in order to achieve something that is better than we have now and enable the kind of innovative scholarship that more openness will drive’.

and a note of optimism by Prof Martin Paul Eve who said the following when he was asked if there are lessons to be learnt from how open access has been applied to journals so far.

‘…we can learn a lot from how the open access debate has played out. I think we also learn a lot in seeing how compromises were reached within that to get to a point that is far better than a decade ago in terms of open access for journals…Momentum is growing, and acceptance is growing. And the idea that we don’t lose quality when things are available openly is growing. All these things are positive and I think we need to take those positives, articulate them from the start and see where that takes us rather than re-inventing the wheel, having the same argument, the same debates, and ending up in the same place, probably, but 20 years from now rather that in the next decade’.

Recordings and most of the presentations are available in the University of Cambridge institutional repository, Apollo as well as the OSC YouTube channel. We would like to acknowledge that this symposium was supported by the Arcadia Fund, a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin.

References

(1) Source: Eve, M.P. et al., (2017). Cost estimates of an open access mandate for monographs in the UK’s third Research Excellence Framework. Insights. https://doi.org/10.1629/uksg.392)

Published 23 October 2019

Written by Dr Lauren Cadwallader and Maria Angelaki