Authors: Emma Gilby, Matthias Ammon, Rachel Leow and Sam Moore

This is the first in a series of blog posts, presenting the reflections of the Working Group on Open Research in the Humanities. The working group aimed to reframe open research in a way that was more meaningful to humanities disciplines, and their work will inform the University of Cambridge approach to open research. This post introduces the working group and provides a top level overview of the issues the group discussed between July and December 2021.

The Working Group on Open Research in the Humanities was chaired by Prof. Emma Gilby (MMLL) with Dr. Rachel Leow (History), Dr. Amelie Roper (UL), Dr. Matthias Ammon (MMLL and OSC), Dr. Sam Moore (UL), Prof. Alexander Bird (Philosophy), and Prof. Ingo Gildenhard (Classics). We met for four meetings in July, September, October and December 2021, with a view to steering and developing services in support of Open Research in the Humanities. We aimed notably to offer input on how to define Open Research in the Humanities, how to communicate effectively with colleagues in the Arts and Humanities (A&H), and how to reinforce the prestige around Open Research. We hope to add our perspective to the debate on Open Science by providing a view ‘from the ground’ and from the perspective of a select group of humanities researchers. These disciplinary considerations inevitably overlap, in some measure, with the social sciences and indeed some aspects of STEM, and we hope that they will therefore have a broad audience and applicability.

Academics in A&H are, in the main, deeply committed to sharing their research. They consider their main professional contribution to be the instigation and furthering of diverse cultural conversations. They also consider open public access to their work to be a valuable goal, alongside other equally prominent ambitions: aiming at research quality and diversity, and offering support to early career scholars in a challenging and often precarious employment landscape.

Although A&H cover a diverse range of disciplines, it is possible to discern certain common elements which guide their profile and impact. These common elements also guide the discussion that follows.

- A&H colleagues tend to produce longer and more intensively edited books and articles. The in-depth study of 80,000 words+ is still considered to be a particularly useful and therefore prestigious research output. This work is deeply reliant upon the additional work of librarians, translators, copy editors, managing editors, general editors, etc., all of whom are highly skilled professionals in their own right.

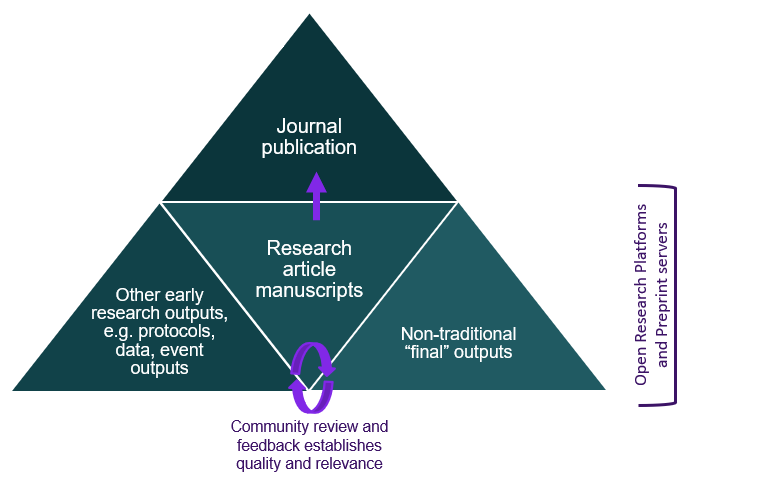

- A&H scholars would often go further than our STEM colleagues in wanting the open access version of our work to correspond to the final version of record, as opposed to an unformatted (and therefore unfinished) ‘accepted manuscript’ or ‘preprint’. This is because, as just mentioned, editorial activity (the work as process) is a vital part of the end result (the work as product). Moreover, in A&H, citations often refer to individual pages rather than to an article as a whole, so having access to versions with differing pagination is unhelpful for authors and readers.

- A&H work can be vastly commercially profitable, especially in the entertainment industries, but often has an indirect commercial use value, and one does not get the sense that profiteering is a discipline-wide issue. Far fewer A&H journals would be owned by for-profit multinational businesses. They tend instead to be closely connected to scholarly societies, who themselves plough their profits back into running conferences and supporting communities and early career scholars, while maintaining a diverse set of publishing arrangements with university or smaller scholarly presses. The complaint from colleagues in STEM that profit-oriented journals ‘take our work and then sell it back to us’ is less frequently heard in A&H contexts; A&H researchers would perhaps tend to have a less antagonistic relationship to publishers than in STEM.

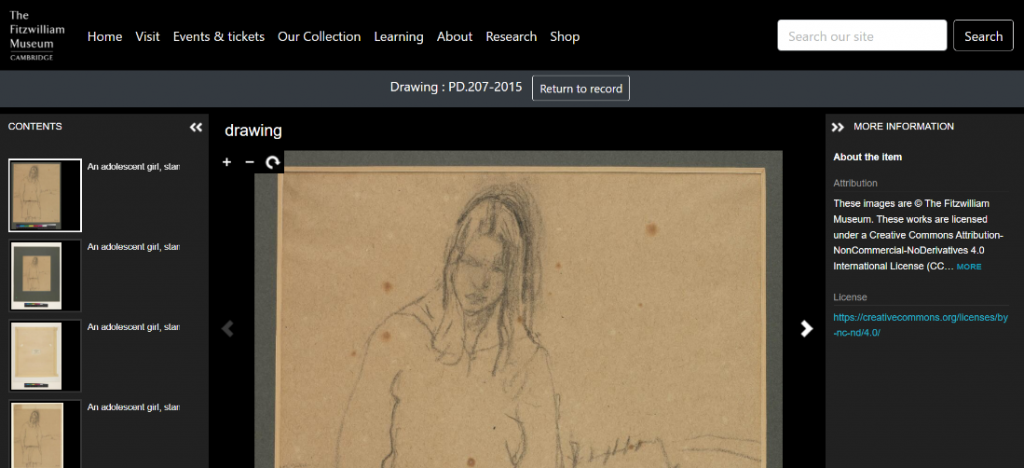

- A&H scholars do not tend to produce data from scratch via experiment. The material that we work with would often be available in the form of printed texts or images, or generated via discussion in the case of, say, oral histories or interview pieces. However, we also often deal with data that we do not own. In these cases, we pay to publish from private archives or collections or from other resources that are under copyright.

- A much smaller percentage of A&H research is funded by the research councils than is the case in the STEM subjects. To an extent, this follows from the fact that (notwithstanding the copyright payments mentioned above) A&H research is often less expensive to carry out than STEM research, requiring less equipment, space etc. Even so, there is a significant funding gap in the A&H, often partially filled by registered charities such as the Leverhulme Trust, the British Academy, etc. Department and faculty research budgets are vanishingly small.

- Many A&H researchers (often in fields such as music, art history, drama and so on) are located outside the higher education system altogether, working for instance in museums, galleries, private houses or collections, theatres, or charities.

- It is less the case in the A&H than in the sciences that English is the international language of communication. Indeed, publication in foreign-language journals or the translation of one’s books into languages other than English would be a particular mark of prestige in the A&H, demonstrating international reach, irrespective of the size of the publics reached.

The Five Pillars of Open Research in the Arts and Humanities: Opportunities for Cultural Change

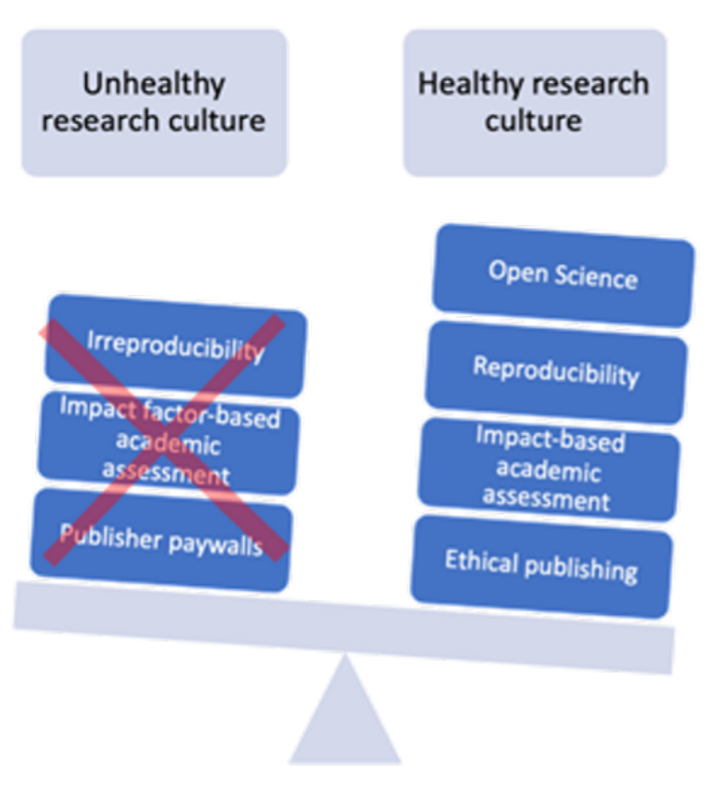

The Working Group set itself the task of revisiting a document produced in 2018 by the League of European Research Universities (LERU): Open Science and its Role in Universities: A Roadmap for Cultural Change. LERU’s ‘eight dimensions of open science’, often referred to as the ‘eight pillars’, are as follows:

- The Future of Scholarly Publishing

- FAIR data (findable, accessible, interoperable and reproducible)

- The European Open Science Cloud (EOSC)

- Education and Skills

- Rewards and Incentives

- Next-generation Metrics

- Research Integrity

- Citizen Science

The outline and detailed descriptions of the ‘eight pillars’ are often explicitly or implicitly science-based, and reflect assumptions about knowledge production in the STEM disciplines. We have now rewritten these to give the ‘five pillars of open research in the arts and humanities’. A more detailed examination of each pillar follows, as a way to structure our recommendations for the ways in which our institution, and HE institutions in general, can support open research in the A&H. In each of the five sections, detailed in the next five blog posts, opportunities are noted and recommendations for institutional support, development and training are given.

- The Future of Scholarly Communication

- CORE Data

- Research Integrity and Care

- Public Engagement

- Research Evaluation

The full, citable report is available in Apollo: https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.86734