Welcome to International Data Week. The Office of Scholarly Communication is celebrating with a series of blog posts about data, starting with a summary of an event we held in July.

On 29 July 2016 the Cambridge Research Data Team joined forces with the Science and Engineering South Consortium to organise a one day conference at the Murray Edwards College to gather researchers and practitioners for a discussion about the existing barriers to data sharing. The whole aim of the event was to move beyond compliance with funders’ policies. We hoped that the community was ready to change the focus of data sharing discussions from whether it is worth sharing or not towards more mature discussions about the benefits and limitations of data sharing.

On 29 July 2016 the Cambridge Research Data Team joined forces with the Science and Engineering South Consortium to organise a one day conference at the Murray Edwards College to gather researchers and practitioners for a discussion about the existing barriers to data sharing. The whole aim of the event was to move beyond compliance with funders’ policies. We hoped that the community was ready to change the focus of data sharing discussions from whether it is worth sharing or not towards more mature discussions about the benefits and limitations of data sharing.

What are the barriers?

So what are the barriers to effective sharing of research data? There were three main barriers identified, all somewhat related to each other: poorly described data, insufficient data discoverability and difficulties with sharing personal/sensitive data. All of these problems arise from the fact that research data does not always shared in accordance to FAIR principles: that data is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Re-usable.

Poorly described data

The event started with an inspiring keynote talk from Dr Nicole Janz from the Department of Sociology at the University of Cambridge: “Transparency in Social Science Research & Teaching”. Nicole regularly runs replication workshops at Cambridge, where students select published research papers and they work hard for several weeks to reproduce the published findings. The purpose of these workshop is to allow students to learn by experience on what is important in making their own work transparent and reproducible to others.

Very often students fail to reproduce the results. Frequently, the reasons for failures are insufficient methodology available, or simply the fact that key datasets were not made available. Students learn that in order to make research reproducible, one not only needs to make the raw data files available, but that the data needs to be shared with the source code used to transform it and with written down methodology of the process, ideally in a README file. While doing replication studies, students also learn about the five selfish benefits of good data management and sharing: data disasters are avoided, it is easier to write up papers from well-managed data, transparent approach to sharing makes the work more convincing to reviewers, the continuity of research is possible and researchers can build their reputation for being transparent. As a tip for researchers, Nicole suggested always asking a colleague to try to reproduce the findings before submitting a paper for peer-review.

The problem of insufficient data description/availability was also discussed during the first case study talk by Dr Kai Ruggeri from the Department of Psychology, University of Cambridge. Kai reflected on his work on the assessment of happiness and wellbeing across many European countries, which was part of the ESRC Secondary Data Analysis Initiative. Kai re-iterated that missing data make the analysis complicated and sometimes prevent one from being able to make effective policy recommendations. Kai also stressed that frequently the choice of baseline for data analysis can affect the final results. Therefore, proper description of methodology and approaches taken is key for making research reproducible.

Insufficient data discoverability

We also heard several speakers describing problems with data discoverability. Fiona Nielsen founded Repositive – a platform for finding human genomic data. Fiona founded the platform out of frustration that genomic data was so difficult to find and access. Proliferation of data repositories made it very hard for researchers to actually find what they need.

We also heard several speakers describing problems with data discoverability. Fiona Nielsen founded Repositive – a platform for finding human genomic data. Fiona founded the platform out of frustration that genomic data was so difficult to find and access. Proliferation of data repositories made it very hard for researchers to actually find what they need.

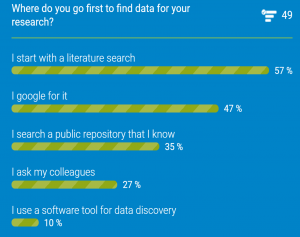

Fiona started with doing a quick poll among the audience: how do researchers look for data? It turned out that most researchers find data by doing a literature research or by googling for it. This is not surprising – there is no search engine enabling looking for information simultaneously across the multiple repositories where the data is available. To make it even more complicated, Fiona reported that in 2015 80PB of human genomic data was generated. Unfortunately, only 0.5PB of human genomic data was made available in a data repository.

Fiona started with doing a quick poll among the audience: how do researchers look for data? It turned out that most researchers find data by doing a literature research or by googling for it. This is not surprising – there is no search engine enabling looking for information simultaneously across the multiple repositories where the data is available. To make it even more complicated, Fiona reported that in 2015 80PB of human genomic data was generated. Unfortunately, only 0.5PB of human genomic data was made available in a data repository.

So how can researchers find the other datasets, which are not made available in public repositories? Repositive is a platform harvesting metadata from several repositories hosting human genomic data and providing a search engine allowing researchers to simultaneously look for datasets shared in all of them. Additionally, researchers who cannot share their research data via a public repository (for example, due to lack of participants’ consent for sharing), can at least create a metadata record about the data – to let others know that the data exist and to provide them with information on data access procedure.

The problem of data discoverability is however not only related to people’s awareness that datasets exists. Sometimes, especially in the case of complex biological data with a vast amount of variables, it can be difficult to find the right information inside the dataset. In an excellent lightening talk, Jullie Sullivan from the University of Cambridge described InterMine –platform to make biological data easily searchable (‘mineable’). Anyone can simply upload their data onto the platform to make it searchable and discoverable. One example of the platform’s use is FlyMine – database where researchers looking for results of experiments conducted on fruit fly can easily find and share information.

Difficulties with sharing personal/sensitive data

The last barrier to sharing that we discussed was related to sharing personal/sensitive research data. This barrier is perhaps the most difficult one to overcome, but here again the conference participants came up with some excellent solutions. First one came from the keynote speech by Louise Corti – with a talk with a very uplifting title: “Personal not painful: Practical and Motivating Experiences in Data Sharing”.

Louise based her talk on the long experience of the UK Data Service with providing managed access to data containing some forms of confidential/restricted information. Apart from being able to host datasets which can be made openly available, the UKDS can also provide two other types of access: safeguarded access, where data requestors need to register before downloading the data, and controlled data, where requests for data are considered on a case by case basis.

At the outset of the research project, researchers discuss their research proposals with the UKDS, including any potential limitations to data sharing. It is at this stage – at the outset of the research project, that the decision is made on the type of access that will be required for the data to be successfully shared. All processes of project management and data handling, such as data anonymisation and collection of informed consent forms from study participants, are then carried in adherence to that decision. The UKDS also offers protocols clarifying what is going to happen with research data once they are deposited with the repository. The use of standard licences for sharing make the governance of data access much more transparent and easy to understand, both from the perspective of data depositors and data re-users.

Louise stressed that transparency and willingness to discuss problems is key for mutual respect and understanding between data producers, data re-users and data curators. Sometimes unnecessary misunderstandings make data sharing difficult, when it does not need to be. Louise mentioned that researchers often confuse ‘sensitive topic’ with ‘sensitive data’ and referred to a success case study where, by working directly with researchers, UKDS managed to share a dataset about sedation at the end of life. The subject of study was sensitive, but because the data was collected and managed with the view of sharing at the end of the project, the dataset itself was not sensitive and was suitable for sharing.

As Louise said “data sharing relies on trust that data curators will treat it ethically and with respect” and open communication is key to build and maintain this trust.

So did it work?

The purpose of this event was to engage the community in discussions about the existing limitation to data sharing. Did we succeed? Did we manage to engage the community? Judging by the fact that we have received twenty high quality abstract applications from researchers across various disciplines for only five available case study speaking slots (it was so difficult to shortlist the top five ones!) and also because the venue was full – with around eighty attendees from Cambridge and other institutions, I think that the objective was pretty well met.

The purpose of this event was to engage the community in discussions about the existing limitation to data sharing. Did we succeed? Did we manage to engage the community? Judging by the fact that we have received twenty high quality abstract applications from researchers across various disciplines for only five available case study speaking slots (it was so difficult to shortlist the top five ones!) and also because the venue was full – with around eighty attendees from Cambridge and other institutions, I think that the objective was pretty well met.

Additionally, the panel discussion was led by researchers and involved fifty eight active users on the Sli.do platform for questions to panellists. There were also questions asked outside of Sli.do platform. So overall I feel that the event was a great success and it was truly fantastic to be part of it and to see the degree of participant involvement in data sharing.

Another observation is also the great progress of the research community in Cambridge in the area of sharing: we have successfully moved away from discussions whether research data is worth sharing to how to make data sharing more FAIR.

It seems that our intense advocacy, and the effort of speaking with over 1,800 academics from across the campus since January 2015 paid off and we have indeed managed to build an engaged research data management community.

Read (and see!) more:

- Twitter story of the event

- All presentations, videos and photos from the event

- Blog post by Dr Kirstie Whitaker – one of the event’s attendees