Perhaps we should start this discussion with a definition of ‘impact’. The term impact is used by many different groups for different purposes, and much to the chagrin of many researchers it is increasingly a factor in the Higher Education Funding Councils for England’s (HECFE) Research Excellence Framework. HEFCE defined impact as:

‘an effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life, beyond academia’.

So we are talking about research that affects change beyond the ivory tower. What follows is a discussion about strengthening the chances of increasing the impact of research.

Is publishing communicating research?

Publishing a paper is not a good way of communicating work. There is some evidence that much published work is not read by anyone other than the reviewers. During an investigation of claims that huge numbers of papers were never cited, Dahlia Remler found that:

- Medicine – 12% of articles are not cited

- Humanities – 82% of articles are not cited – note however that their prestigious research is published in books, however many books are rarely cited too.

- Natural Sciences – 27% of articles are never cited

- Social Sciences – 32% of articles are never cited

Hirsch’s 2005 paper: An index to quantify and individual’s scientific research output, proposing the h index – defined as the number of papers with citation number ≥h. So an h index of 5 means the author has at least 5 papers with at least 5 citations. Hirsch suggested this as a way to characterise the scientific output of researchers. He noted that after 20 years of scientific activity, an h index of 20 is a ‘successful scientist’. When you think about it, 20 other researchers are not that many people who found the work useful. And that ignores those people who are not ‘successful’ scientists who are, regardless, continuing to publish.

Making the work open access is not necessarily enough

Open access is the term used for making the contents of research papers publicly available – either by publishing them in an open access journal or by placing a copy of the work in a subject or institutional repository. There is more information about open access here.

I am a passionate supporter of open access. It breaks down cost barriers to people around the world, allowing a much greater exposure of publicly funded research. There is also considerable evidence showing that making work open access increases citations.

But is making the work open access enough? Is a 9.5MB pdf downloadable onto a telephone, or through a dail-up connection? If the download fails at 90% you get nothing. Some publishing endeavours have recogised this as an issue, such as the Journal of Humanitarian Engineering (JHE), which won the Australian Open Access Support Group‘s 2013 Open Access Champion award for their approach to accessibility.

Language issues

The primary issue, however is the problem of understandability. Scientific and academic papers have become increasingly impenetrable as time has progressed. It’s hard to believe now that at the turn of last century scientific articles had the same readability as the New York Times.

‘This bad writing is highly educated’ is a killer sentence from Michael Billig’s well researched and written book ‘Learn to Write Badly: How to Succeed in the Social Sciences‘. This phenomenon is not restricted to the social sciences, specialisation and a need to pull together with other members of one’s ‘tribe‘ mean that academics increasingly write in jargon and specialised language that bears little resemblance to the vernacular.

There are increasing arguments for scientific communication to the public being part of formal training. In a previous role I was involved in such a program through the Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science. Certainly the opportunities for PhD students to share their work more openly have never been more plentiful. There are many three minute thesis competitions around the world. Earlier this year the British Library held a #Share your thesis competition where entrants were first asked to tweet why their PhD research is/was important using the hashtag #ShareMyThesis. The eight shortlisted entrants were asked to write a short article (up to 600 words) elaborating on their tweet and explaining why their PhD research is/was important in an engaging and jargon-free way.

Explaining work in understandable language is not ‘dumbing it down’. It is simply translating it into a different language. And students are not restricted to the written word. In November the eighth winner of the annual ‘Dance your PhD‘ competition sponsored by Science, Highwire Press and the AAAS will be announced.

Other benefits

There is a flow-on effect from communicating research in understandable language. In September, the Times Higher Education recently published an article ‘Top tips for finding a permanent academic job‘ where the information can be summarised as ‘communicate more’.

The Thinkable.org group’s aim is to widen the reach and impact of research projects using short videos (three minutes or less). The goal of the video is to engage the research with a wide audience. The Thinkable Open Innovation Award is a research grant that is open to all researchers in any field around the world and awarded openly by allowing Thinkable researchers and members to vote on their favourite idea. The winner of the award receives $5000 to help fund their research. This is specifically the antithesis of the usual research grant process where grants “are either restricted by geography or field, and selected via hidden panels behind closed doors”.

But the benefit is more than the prize money. This entry from a young Uni of Manchester PhD biomedical student did not win, but thousands of people engaged in her work in just few weeks of voting.

Right. Got the message. So what do I need to do?

Researcher Mike Taylor pulled together a list of 20 things a researcher needs to do when they publish a paper. On top of putting a copy of the paper in an institutional or subject repository, suggestions include using various general social media platforms such as Twitter and blogs, and also uploading to academic platforms.

The 101 Innovations in Scholarly Communication research project run from the University of Utrecht is attempting to determine scholarly use of communication tools. They are analysing the different tools that researchers are using through the different phases of the research lifecycle – Discovery, Analysis, Writing, Publication, Outreach and Assessment through a worldwide survey of researchers. Cambridge scholars can use a dedicated link to the survey.

There are a plethora of scholarly peer networks which all work in slightly different ways and have slightly different foci. You can display your research into your Google Scholar or CarbonMade profile. You can collate the research you are finding into Mendeley or Zotero. You can also create an environment for academic discourse or job searching with Academia.edu, ResearchGate and LinkedIn. Other systems include Publons – a tool to register peer reviewing activity.

Publishing platforms include blogging (as evidenced here), Slideshare, Twitter, figshare, Buzzfeed. Remember, this is not about broadcasting. Successful communicators interact.

Managing an online presence

Kelli Marshall from DePaul University asks ‘how might academics—particularly those without tenure, published books, or established freelance gigs—avoid having their digital identities taken over by the negative or the uncharacteristic?’

She notes that as an academic or would-be academic, you need to take control of your public persona and then take steps to build and maintain it. If you do not have a clear online presence, you are allowing Google, Yahoo, and Bing to create your identity for you. There is a risk that the strongest ‘voices’ will be ones from websites such as Rate My Professors.

Digital footprint

Many researchers belong to an institution, a discipline and a profession. If these change your online identity associated with them will also change. What is your long term strategy? One thing to consider is obtaining a persistent unique identifier such as an ORCID – which is linked to you and not your institution.

When you leave an institution, you not only lose access to the subscriptions the library has paid for, you also lose your email address. This can be a serious challenge when your online presence in academic social media sites like Academia.edu and ResearchGate are linked to that email address. What about content in a specific institutional repository? Brian Kelly discussed these issues at a recent conference.

We seem to have drifted a long way from impact?

The thing is that if it can be measured it will be. And digital activity is fairly easily measured. There are systems in place now to look at this kind of activity. Altmetrics.org moves beyond the traditional academic internal measures of peer review, Journal Impact Factor (JIF) and the H-index. There are many issues with the JIF, not least that it measures the vessel, not the contents. For these reasons there are now arguments such as the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) which calls for the scrapping of the JIF to assess a researcher’s performance. Altmetrics.org measures the article itself, not where it is published. And it measures the activity of the articles beyond academic borders. To where the impact is occurring.

So if you are serious about being a successful academic who wants to have high impact, managing your online presence is indeed a necessary ongoing commitment.

NOTE: On 26 September, Dr Danny Kingsley spoke on this topic to the Cambridge University Alumni festival. The slides are available in Slideshare. The Twitter discussion is here.

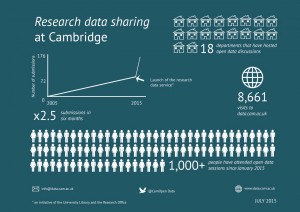

This infographic demonstrates how successful the Research Data Facility has been. Prepared by Laura Waldoch from the University Library, it is

This infographic demonstrates how successful the Research Data Facility has been. Prepared by Laura Waldoch from the University Library, it is