This blog accompanies a talk Danny Kingsley gave to the RLUK Conference held at the British Library on 9-11 March 2016. The slides are available and the Twitter hashtag from the event was #rluk16

The talk centred around a debate piece written with my long standing collaborator, Dr Mary Anne Kennan, published in August 2015: Open Access: The Whipping Boy for Problems in Scholarly Publishing. This original 10,000 word article was the starting point for a debate where five people provided rebuttals to our position and we were then given the opportunity to write a rejoinder to these. All the articles were published together.

I have included a précis of the article below as Annex 1, but that is not what the talk was about – what I wanted to discuss was the unexpected progression of the piece and what that revealed to us as authors working in Scholarly Communication.

After we submitted the original piece we sent through several suggestions (including names and contact details) to the Editor for people who might want to contribute. These primarily included practitioners in the Open Access space:

- Funders

- Library staff

- Research managers

- Editors

- Publishers

- Policy makers

There was considerable difficulty in locating people who were prepared to contribute. We are still unsure why this was the case – it may have been a time issue, the fact that this was an academic publication and we were asking administrative professionals, or that it was potentially politically sensitive. On the Editor’s suggestion we sent some personal requests to contacts to ask them to participate. However, in the end four of the five people who wrote rebuttals were researchers in the Information Systems field.

This process made the whole production very protracted. There was a two-year period between the first approach from the journal and publication. The production process from the start of the writing period was 18 months – the actual dates are listed as Annex 2 below.

Same old, same old – the responses

Reading the rebuttals from the four Information Systems researchers, two things become obvious. First, none of them actually addressed the posits we had presented in our original debate piece – which, after all was the point of the exercise.

Second, a theme began to emerge, demonstrated by these snippets:

- “Before discussing that in detail we need to know what the current situation is regarding OA publishing in IS”

- “We now discuss four fundamental points regarding scholarly communication. We begin by asking what constitutes the main building blocks of the scholarly communication system”

- “Before examining the current state of scholarly publication, let us set some parameters for this discussion”

- “I think the argument would benefit from more systematically analyzing the current system of scholarly publishing…”

In each case the authors chose to undertake their own analysis of scholarly publishing – sometimes apparently unaware that this is a long established area of research.

So what does this tell us?

Lesson 1 – ‘Engagement’ is not working

One thing that was striking about this process was that each contributor came to their own conclusion that Open Access is something we should aim towards. While this is a ‘good thing’ for Open Access advocacy, it is not scalable. If we wait for every researcher to come to their own personal epiphany about Open Access we will never have high levels of uptake.

There has been a long standing belief and practice in Open Access that if the research community were only more aware of the issues in scholarly publishing then they would come on board with Open Access. I am entirely guilty of this myself. However after a decade of trying, it is fairly safe to say that engagement has not worked.

One conclusion to take away from this experience is we must enable the academic community to disseminate their work openly. It must happen around them.

Lesson 2 – The research area of scholarly communication is not well recognised

The concept of an academic discipline is fairly slippery, but it is reasonably safe to say that two things define a discipline – the scholarly literature and language.

Academic ‘communities’ manifest in the form of journals or learned societies. But Scholarly Communication research is traditionally discussed either in a disciplinary specific way in a disciplinary journal (such as part of an editorial), or are published in journals in the sociology of science, communication, librarianship or the information sciences disciplines.

There are two journals that do specifically look at Scholarly Communication – the Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication and Scholarly and Research Communication. I should note that Publications also looks at many issues in this area too.

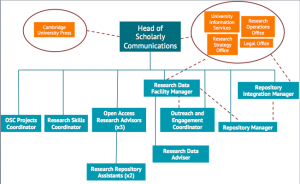

There are now Offices of Scholarly Communication in universities, especially in the US & increasingly in the UK – the Office of Scholarly Communication at Cambridge being a classic example. However there are no Faculties or Departments or Professorial Chairs of Scholarly Communication in existence – that I can find. I am happy to hear about them if they do exist.

And yet people do undertake research in this area. They publish articles, peer review each other’s work, present at conferences. This is academic work.

It might well be a problem of language. Michael Billing’s book ‘Learn to Write Badly: How to succeed in the social sciences’ makes the argument that creating a language that is impenetrable to others is a way of boundary stamping a discipline.

But in the area of Scholarly Communication, many of the words are vernacular – with common meanings that might be different to their specific meaning in the context of the research. A classic example is ‘publish’ which simply means ‘make public’, but within the academic context means that there has been a process of review and revision, branding and attribution. Words like ‘repository’ and ‘mandate’ have caused me some professional grief.

And we are having some trouble with terminology in the Open Access space with publishers. For example the conflation of ‘deposit’ with ‘make available’ – Wiley instructs authors that they cannot deposit until after the embargo. This is wrong. Authors can deposit whenever they like, as long as they don’t make it available until after the embargo. Green Open Access – which means making a copy of the work freely available – has been rather bizarrely interpreted by Elsevier in their Open Access pages as providing a link to the (subscription) article.

The reason there can be such a high level of inaccuracy around language is because it is not ‘officially’ defined anywhere. I should note that the Consortia Advancing Standards in Research Administration Information (CASRAI) may be doing some work in this area.

Problem 1 – Practice versus study

We concluded in our rebuttal that the practice of scholarly communication (as distinct from the study of it) is shared among all academic fields, librarians, publishers, and administrators. Each of these bring their own levels of understanding, perspectives, and involvement in the scholarly communication system.

This can create a problem because practitioners often think they have a good understanding of the issues surrounding the publication process. But according to a 2012 article in the Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication researchers are generally held to have a low awareness of publishing issues and open access opportunities and are confused over copyright issues.

This is a case of the ‘Unknown Unknowns’ – a term coined (to much ridicule) by Donald Rumsfeld in 2003.

Regardless of where individuals sit, however, in all instances there needs to be a base level of competence in this area. Yes I know, I have just said we should not try and engage academics to convert them to Open Access. However what we should be doing is ensuring they have at least a basic understanding of this area for their own professional wellbeing.

One of the conclusions of my 2008 PhD The effect of scholarly communication practices on engagement with open access: An Australian study of three disciplines – where I undertook in-depth interviews with 43 researchers about their publication and communication practices – was that the Master/Apprentice system is broken (see pp177 – 188). We are not equipping our researchers with the information they need to navigate the publication process successfully. This need for education was echoed in a 2014 paper about open access journal quality indicators (itself published in the Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication – notice a pattern?)

Problem – library community also needs to know

But this is not just an issue for the research community. Librarians in the academic space also need to know about these issues. Last year the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) released their (excellent) Scholarly Communication Toolkit. The introductory pages note that the “ACRL sees a need to vigorously re-orient all facets of library services and operations to the evolving technologies and models that are affecting the scholarly communication process.” The reason, they say, is because in order for academic libraries to continue to succeed we need to integrate our work into all aspects of the full cycle of scholarly communication.

The toolkit also notes that there is ‘wide variance’ in the levels of understanding of these issues within our community. If we consider the ‘four stages of competence’ as a rough tool:

- Unconsciously unskilled – we don’t know that we don’t have this skill, or that we need to learn it.

- Consciously unskilled – we know that we don’t have this skill.

- Consciously skilled – we know that we have this skill.

- Unconsciously skilled – we don’t know that we have this skill (it just seems easy).

It would be an ideal situation to have our academic library community sitting at stages three and four. In reality many are at stage two and even at stage one.

But bringing everyone up to speed is a huge challenge. Our experiences in Australia have demonstrated it is extremely difficult to get issues related to scholarly communication into curricula for library training. Many of the skills in this area are learnt ‘on the job’.

There are almost no courses on repository management as demonstrated in this 2012 study published in the (here it is again) Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication. There is a now slightly out of date list of courses in scholarly communication here. Professor Stephen Pinfield did point out after my talk that he is incorporating open access into his library courses. Discussions about open access are also included at Charles Sturt University in subjects where it is related such as Foundations for information Studies, Collections and Research Data Management, but there has been difficulty in securing a subject explicitly on Open Access or even more broadly on scholarly communication.

Even professional training is limited – CILIP offers ‘Institutional repositories and metadata’ and ‘Digital copyright’ but nothing on publishing or open access. One of the positive outcomes of the conference has been an offer to discuss some of these needs with CILIP.

Solution?

So what is the solution? We must shift from managing the academic literature to participating in the generation of it. Librarians can begin by engaging with the academic literature in their area. Suggestions include:

- Reading research that is being published (in your area of librarianship)

- Writing an academic article

- Presenting work at conferences

- Offering your services as a peer reviewer

- Serving on an editorial board

- Collaborating with your academic community on a project and writing about it

When I suggested this at the conference there was some push-back from the audience, defending the benefits of learning on the job. Afterwards, I was approached by a participant who said she had recently published a paper and found the process incredibly instructive. Interestingly, the same thing happened when a speaker urged colleagues to publish an academic paper at LIBER last year. There was again push-back from the audience until one participant said they seconded her statement. He said he thought he knew all about journals because he worked with them but when he published something he realised ‘I didn’t really know anything about it’.

We might have some way to go.

Annex 1 – The original debate piece

In the original debate piece we provided a background to OA’s development and current state – we did not go into great detail because we were limited by the 10,000 word count and we had made some assumptions about prior knowledge.

The piece examined some of the accusations leveled against OA and described why they were false and indeed indicative of a wider set of problems with scholarly communication:

- that OA publishers are predatory,

- that OA is too expensive,

- that self-depositing papers in OA repositories will bring about the end of scholarly publishing.

We then proposed discussions we considered we should be having about scholarly publishing to take advantage of social and technological innovations and move it into the 21st century. These were the monograph issue, management of APCs, improving institutional repositories, needing to make scholarly publishing inclusive and the reward system.

Annex 2 – The times involved in publication

Here are the dates involved in getting the full debate piece to ‘print’:

- First approach from the journal – September 2013

- Agreed to write the piece and first discussion – 10 February 2014

- Submitted the first argument – 26 May 2014

- Submitted amendment based on editor’s comments – 29 May 2014

- Rebuttals sent to us – 18 November 2014

- Deadline for rejoinder – 19 December 2014

- Rejoinder sent (!) – 16 February 2015

- “Publication is with the production editor and will be out ‘anytime’” email – 6 May 2015

- Copy editor’s questions sent to us – 4 June 2015

- Corrected pieces (original & rejoinder) sent to editors – 26 June 2015

- Date of acceptance – 4 July 2015

- Date of publication – 17 August 2015