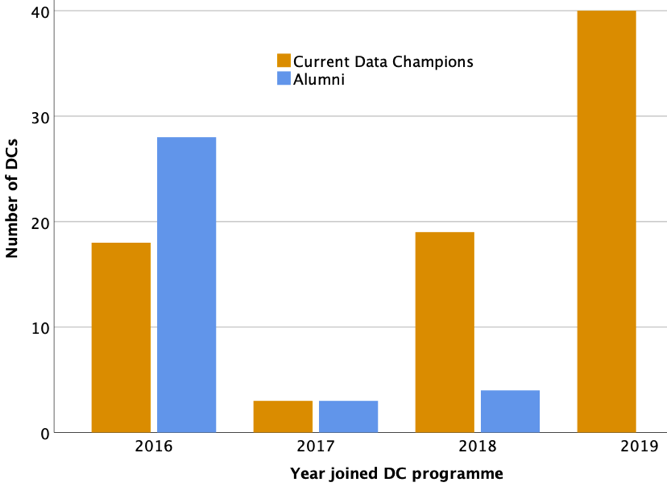

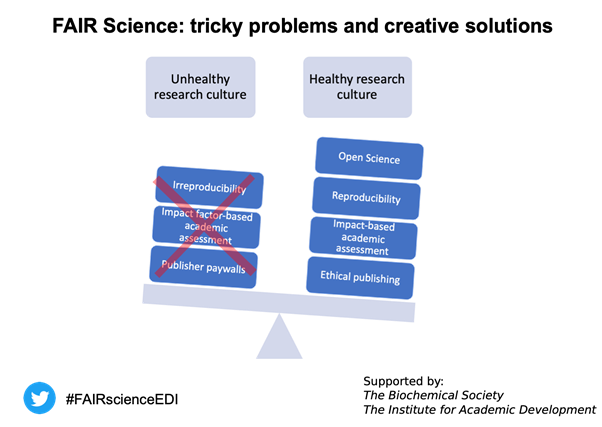

The Cambridge Data Champions are an example of a community of volunteers engaged in promoting open research and good research data management (RDM). Currently entering its third year, the programme has attracted a total of 127 volunteers (86 current, 41 alumni) from diverse disciplinary backgrounds and positions. It continues to grow and has inspired similar initiatives at other universities within and outside the UK (Madsen, 2019). Dr Sacha Jones, Research Data Coordinator at the Office of Scholarly Communication, recently shared information about the programme at ‘FAIR Science: tricky problems and creative solutions’, an Open Science event held on 4th June 2019 at The Queen’s Medical Research Institute in Edinburgh, and organised by a previous Cambridge Data Champion – Dr Ralitsa Madsen. The aim of this event was to disseminate information about Open Science and promote the subsequent set-up of a network of Edinburgh Open Research Champions, with inspiration from the Cambridge Data Champion programme. Running a Data Champion programme, however, is not free of challenges. In this blog, Sacha highlights some of these alongside potential solutions in the hope that this information may be helpful to others. In this vein, Ralitsa adds her insights from ‘FAIR Science’ in Edinburgh and discusses how similar local events may spearhead the development of additional Open Science programmes/networks, thus broadening the local reach of this movement in the UK and beyond.

#FAIRscienceEDI

On 4 June 2019, the University of Edinburgh hosted ‘FAIR Science: tricky problems and creative solutions’ – a one-day event that brought together local life scientists and research support staff to discuss systemic flaws within current academic culture as well as potential solutions. Funded by the Institute for Academic Development and the UK Biochemical Society, the event was popular – with around 100 attendees – featuring both students, postdocs, principal investigators (PIs) and administrative staff. The programme featured talks by a range of local researchers – Dr Ralitsa Madsen (postdoctoral fellow and event organiser), Dr William Cawthorn (junior PI), Prof Robert Semple (Dean of Postgraduate Research and senior PI), Prof Malcolm Macleod (senior PI and member of the UK Reproducibility Network steering group), Prof Andrew Millar (senior PI and Chief Scientific Advisor on Environment, Natural Resources and Agriculture, for Scottish Government), Aki MacFarlene (Wellcome Trust Open Research Programme Officer), Dr Naomi Penfold (Associate Director, ASAPbio), Dr Nigel Goddard and Rory Macneil (RSpace developers) and Robin Rice (Research Data Service, University of Edinburgh), and Dr Sacha Jones (University of Cambridge). All slides have been made available via the Open Science Framework, and “live” tweets can be found via #FAIRScienceEDI.

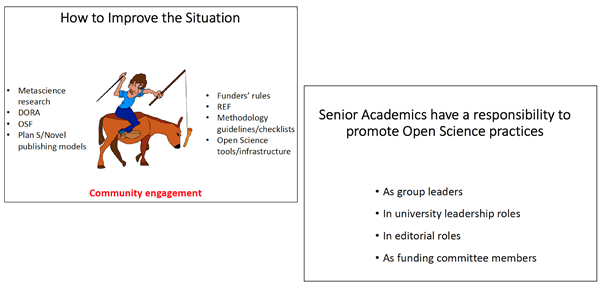

Why is open science important? What is the extent of the reproducibility problem in science, and what are the responsibilities of individual stakeholders? Do all researchers need to engage with open research? Are the right metrics used when assessing researchers for appointment, promotion and funding? What are the barriers to widespread change, and can they be overcome through collective efforts? These were some of the ‘tricky’ problems that were addressed during the first half of the ‘Fair Science’ event, with the second half focussing on ‘creative solutions’, including: abandoning the journal impact factor in favour of alternative and fairer assessment criteria such as those proposed in DORA; preprinting of scientific articles and pre-registration of individual studies; new incentives introduced by funders like the Wellcome Trust who seek to promote Open Science; and data management tools such as electronic lab notebooks. Finally, the event sought to inspire local efforts in Edinburgh to establish a volunteer-driven network of Open Research Champions by providing insight into the maturing Data Champion programme at the University of Cambridge. This was a popular ‘creative solution’, with more than 20 attendees providing their contact details to receive additional information about Open Science and the set-up of a local network.

Overall, community engagement was a recurring theme during the ‘FAIR Science’ event, recognised as a catalyst required for research culture to change direction toward open practices and better science. Robert Semple discussed this in the greatest detail, suggesting that early stage researchers – PhDs and post-docs – are the building blocks of such a community, supported also by senior academics who have a responsibility to use their positions (e.g. as group leaders, editors) to promote open science. “Open Science is a responsibility also of individual groups and scientists, and grass roots efforts will be key to culture shift” (Robert Semple’s presentation). On a larger scale, Aki MacFarlene aptly stated that a supportive research ecosystem is needed to support open research; for example, where institutions as well as funders recognise and reward open practices.

Insights from the Cambridge Data Champion programme

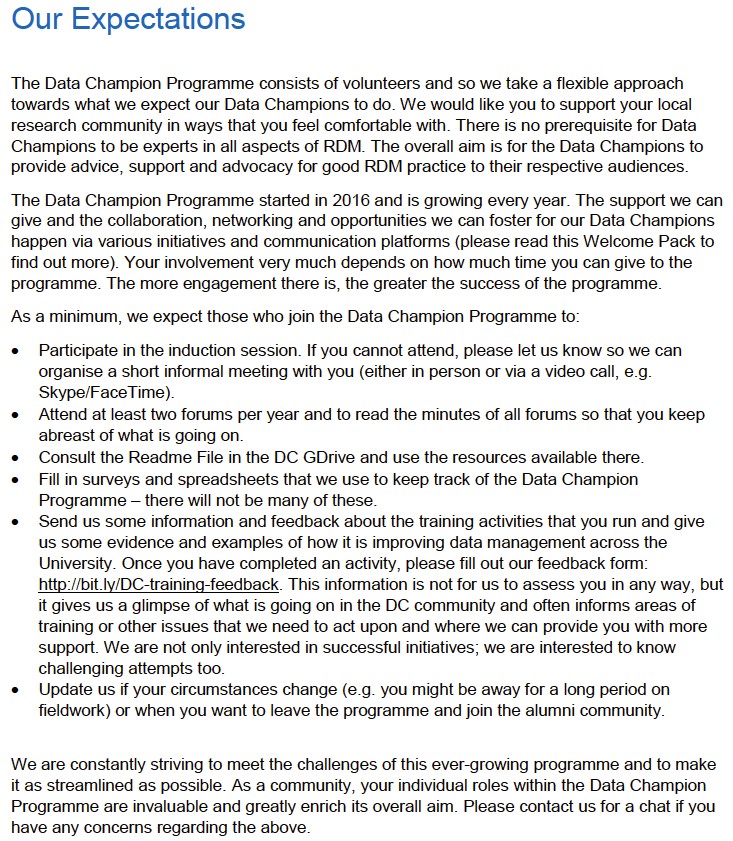

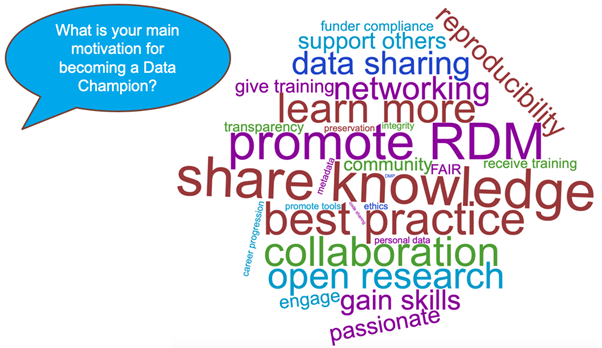

The Data Champions at the University of Cambridge are an example of a community and a source of support for others in the research ecosystem. Promoting good RDM and the FAIR principles are two fundamental goals that Data Champions commit to when they join the programme. For some, endorsing open research practices is a fortuitous by-product of being part of the programme, yet for others, this is a key motivation for joining.

Now that the Data Champion programme has been running for three years, what challenges does it face, and might disclosing these here – alongside ongoing efforts to solve them – help others to establish and maintain similar initiatives elsewhere?

Four main challenges are outlined that the programme either has or continues to experience. These are discussed in increasing scale of difficulty to overcome.

- Support

- Retention

- Disciplinary coverage

- Measuring effectiveness

(See also a recent article about the Data Champion programme by James Savage and Lauren Cadwallader.)

Support

At a basic level, an initiative like the Data Champion programme needs both financial and institutional support. The Data Champions commit their time on a voluntary basis, yet the management of the programme, its regular events and occasional ad hoc projects all require funds. Currently, the programme is secure, but we continue to seek funding opportunities to support a community that is both expanding and deserving of reward (e.g. small grants awarded to Data Champions to support their ‘championing’ activities). Institutional support is already in place and hopefully this will continue to consolidate and grow now that the University has publicly committed to supporting open research.

Retention

Not all Data Champions who join will remain Data Champions. In fact, there is a growing community of alumni Data Champions. There are currently 41 alumni Data Champions. From the feedback provided by just over half of these, 68% left the programme because they left the University of Cambridge (as expected given that the majority of Data Champions are either post-docs or PhD students), and 32% left because of a lack of time to commit to the role. Of course, there might be other reasons that we are not aware of, and we cannot speculate here in the absence of data. Feedback from Data Champions is actively sought and is an essential part of sustaining and developing this type of community.

We are exploring various methods to enhance retention. To combat the pressures of individuals’ workloads, we are being transparent about the time that certain activities will involve – a task or process may be less overwhelming when a time estimate is provided (cf ‘this survey should take approximately ten minutes to complete’). We also initiated peer-mentoring amongst Data Champions this year, in part to encourage a stronger community. We are attempting to enhance networking within the community in other ways, during group discussion sessions in the bimonthly forums, and via a virtual space where Data Champions can view each other’s data-related specialisms – with mutual support and collaboration as intended by-products. These are just a few examples, and given that Data Champions are volunteers, retention is one of several aspects of the programme that requires frequent assessment.

Disciplinary coverage

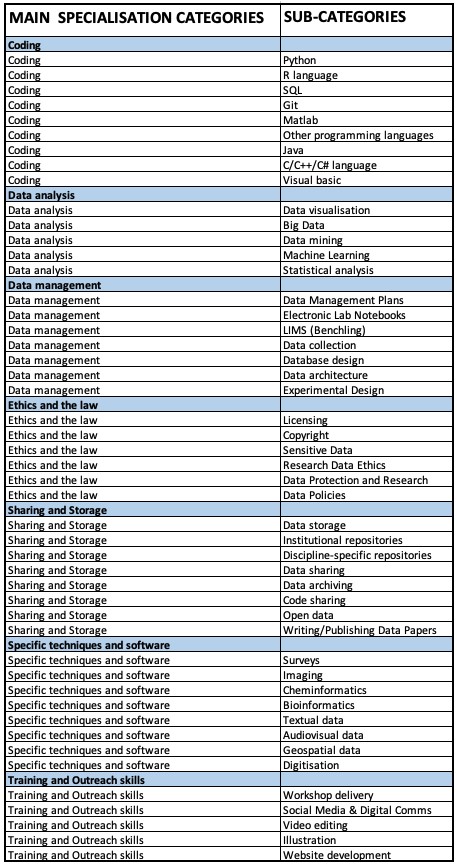

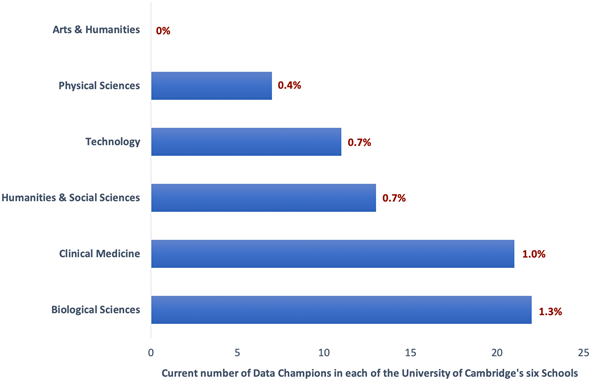

Cambridge has six Schools – Arts and Humanities, Humanities and Social Sciences, Biological Sciences, Physical Sciences, Clinical Medicine, and Technology – with faculties, departments, centres, units, institutes nested within these. The ideal situation would be for each research community (e.g. a department) to be supported by at least one Data Champion. Currently this is not the case, and the distribution of Data Champions across the different disciplinary areas is patchy. Biological Sciences is relatively well-represented by Data Champions (there are 22 Data Champions to represent around 1742 researchers in the School, i.e. 1.3%) (see bar chart below). There is a clear bias towards STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) disciplines, yet representation in the social sciences is fair. At the more extreme end is an absence of Data Champions in the Arts and Humanities. We are looking to resolve this via a more targeted approach, guided in part by insights gained into researcher needs via the OSC’s training programme for arts, humanities and social sciences researchers.

Measuring effectiveness

Determining how well the Data Champion programme is working is a sizeable challenge, as discussed previously. In those research communities represented by Data Champions, do we see improvements in data management, do we see a greater awareness of the FAIR principles, is there a change in research culture toward open research? These aspects are extremely difficult to measure and to assign to cause and effect, with multiple confounding factors to consider. We are working on how best to do this without overloading Data Champions and researchers with too many administrative tasks (e.g. surveys, questionnaires, etc.). Yet, the crux is for there to exist good communication and exchange of information between us (as a unit that is centrally managing the Data Champion programme) and the Data Champions, and between the Data Champions and the researchers who they are reaching out to and working with. We need to be the recipients of this information so that we can characterise the programme’s effectiveness and make improvements. As a start, the bimonthly Data Champion forums are used as an ideal venue to exchange and sound out ideas about best approaches, so that decisions on how to measure the programme’s impact lie also with the Data Champions.

A fifth challenge – recognition and reward

At the ‘FAIR Science’ event, two speakers (Naomi Penfold and Robert Semple) made a plea for those researchers who practise open science to be recognised for this – a change in reward culture is required. In a presentation centred on the misuse of metrics, Will Cawthorn referred to poor mental health in researchers as a result of the pressures of intrinsic but flawed methods of assessment. Understandably, DORA was mentioned multiple times at ‘FAIR Science’, and hopefully, with multiple universities including the University of Cambridge and University of Edinburgh as recent signatories of DORA, this marks the first steps toward a healthier and fairer researcher ecosystem. This may seem rather tangential to the Data Champions, but it is not: 66% of Data Champions, current and alumni, are or have been researchers (e.g. PhDs, post-docs, PIs). Despite the pressures of ‘publish or perish’, they have given precious time voluntarily to be a Data Champion and require recognition for this.

This raises a fifth challenge faced by the programme – how best to reward Data Champions for their contributions? Effectively addressing this may also help, via incentivisation, toward meeting three of the four challenges above – retention, coverage and measurement. While there is no official reward structure in place (see Higman et al. 2017), the benefits of being part of the programme are emphasised (networking opportunities, skills development, online presence as an expert, etc.), and we write to Heads of Departments so that Data Champions are recognised officially for their contributions. Is this enough? Perhaps not. We will address this issue via discussions at the September forum – how would those who are PhD students, post-docs, PIs, librarians, IT managers, data professionals (to name a few of the roles of Data Champions) like to be rewarded? In sharing these thoughts, we can then see what can be done.

Towards growing communities of volunteers

The Cambridge Data Champion programme is one among several UK- and Europe-wide initiatives that seek to promote good RDM and, more generally, Open Science. Their emergence speaks to a wider community interest and engagement in identifying solutions to some of the key issues haunting today’s academic culture (Madsen 2019). While the foundations of a network of Edinburgh Open Research Champions are still being laid, TU Delft in the Netherlands has already got their Data Champion programme up and running with inspiration from Cambridge. Independently, several Universities in the UK have also established their own Open Research groups, many of which are joined together through the recently established UK Reproducibility Network (UKRN) and the associated UK Network of Open Research Working Groups (UK-ORWG). Such integration fosters network crosstalk and is a step in the right direction, giving volunteers a stronger sense of ‘belonging’ while also actively working towards their formal recognition. Network crosstalk allows for beneficial resource sharing through centralised platforms such as the Open Science Framework or through direct knowledge exchange among neighbouring institutions. Following ‘FAIR Science’ in Edinburgh, for example, a meeting to discuss its outcome(s) involved members from Glasgow University’s Library Services (Valerie McCutcheon, Research Information Manager) and the UKRN’s local lead at Aberdeen University (Dr Jessica Butler, Research Fellow, Institute of Applied Health Science). Thus, similar to plans in Aberdeen, the ‘FAIR Science’ organisers are currently working with Edinburgh University’s Research Data Support team to adapt an Open Science survey developed and used at Cardiff University to guide the development of a specific Open Science strategy. This reflects the critical requirements for such strategies to be successful – active peer-to-peer engagement and community involvement to ensure that any initiatives match the needs of those who ought to benefit from them.

The long-term success of Open Science strategies – and any associated networks – will also hinge upon incorporation of formal recognition, as alluded to in the context of the Cambridge Data Champion programme. The importance of formal recognition of Open Science volunteers is also exemplified in SPARC Europe’s recent initiative – Europe’s Open Data Champions – which aims to showcase Open Data leaders who help ‘to change the hearts and minds of their peers towards more Openness’.

For formal recognition to gain traction, it will be critical to work towards recruitment of several prominent senior academics on board the Open Science wagon. By virtue of their academic status, such individuals will be able to put Open Science credentials high on the agenda of funding and academic institutions. Indeed, the establishment of the UKRN can be ascribed to a handful of senior researchers who have been able to secure financial support for this initiative, in addition to inspiring and nucleating local engagement across several UK universities. The ‘FAIR Science’ experience in Edinburgh supports this view. While difficult to prove, its impact would likely have been minimal without the involvement of prominent senior academics, including Professor Robert Semple (Dean of Postgraduate Research), Professor Malcolm Macleod (UKRN steering group member) and Professor Andrew Millar (Chief Scientific Advisor on Environment, Natural Resources and Agriculture, for Scottish Government). Thus, in addition to targeted and continuous communication by the ‘FAIR Science’ organisers before and after the event, ongoing efforts to establish a network of Edinburgh Open Research Champions has been dependent on these senior academics and their ability to mobilise essential forces throughout the University of Edinburgh.

Top-down or bottom-up?

Establishing and maintaining a champions initiative need not be conceived of as succeeding via either a top-down or bottom-up approach. Instead, a combination of the best of both of these approaches is optimal, as hopefully comes across here. The emphasis on such initiatives being community driven is essential, yet structure is also required so as to ensure their maintenance and longevity. Hierarchies have little place in such communities – there are enough of these already in the ‘researcher ecosystem’ – and the beauty of such initiatives is that they bring together people from various contexts (e.g. in terms of role, discipline, institution). In this sense, the Cambridge Data Champions community is especially robust because of its diversity, being comprised of individuals who derive from highly varied roles and disciplinary backgrounds. Every champion brings their own individual strengths; collectively, this is a powerful resource in terms of knowledge and skills. Through acting on these strengths and acknowledging their responsibilities (e.g. to influence, teach, engage others), and by being part of a community like those described here, champions have the opportunity to make perhaps a wider contribution to research than ever anticipated, and certainly one that enhances its overall integrity.

References

Higman, R., Teperek, M. & Kingsley, D. (2017). Creating a community of Data Champions. International Journal of Digital Curation 12 (2): 96–106. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2218/ijdc.v12i2.562

Madsen, R. (2019). Scientific impact and the quest for visibility. The FEBS Journal. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.15043

Savage, J. & Cadwallader, L. (2019). Establishing, Developing, and Sustaining a Community of Data Champions. Data Science Journal 18 (23): 1–8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2019-023

Published 16 September 2019

Written by Dr Sacha Jones and Dr Ralitsa Madsen