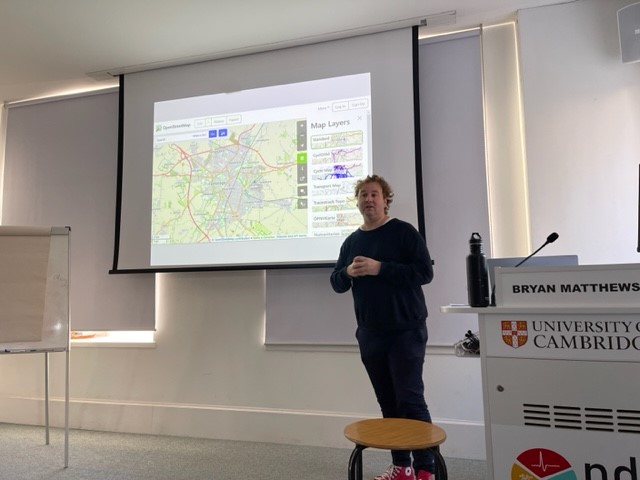

The November Data Champion forum was a geography/geospatial data themed edition of the bi-monthly gathering, this time hosted by the Physiology department. As usual, the Data Champions in attendance were treated to two presentations. Up first was Martin Lucas-Smith from the Department of Geography who introduced the audience to the OpenStreetMap (OSM) project, a global community mapping project using crowdsourcing. Just as Wikipedia is for textual information, OSM results in a worldwide map created by everyday people who map the world themselves. The resulting maps can vary in terms of its focus such as the transport map, which is a map which shows public transport lanes like railways, buses and trams worldwide, and the humanitarian map, which is an initiative dedicated to humanitarian action through open mapping. Martin is personally involved in a project called CycleStreets which, as the name implies, uses open mapping of bicycle infrastructure. The Department of Geography uses OSM as a background for its Cambridge Air Photos websites. Projects like these, Martin highlighted, demonstrate how community gets generated around open data.

CycleStreets: Martin at the November 2023 Data Champion Forum

In his presentation, Martin explained the mechanics of OSM such as its data structure, how the maps are edited, and how data can be used in systems like routing engines. Editing the maps and the decision-making processes that go behind how a path is represented visually on the map is the point where the OSM community comes to action. While the data in OSM consists primarily of geometric points (called ‘Nodes’) and lines (called ‘Ways’) coupled with tags which denotes metadata values, the norms about how to define this information can only come about by consensus from the OSM community. This is perhaps different to more formal database structures that might be employed within corporate efforts such as Google. Because of its widespread crowdsourced nature, OSM tends to be more detailed than other maps for less well-served communities such as people cycling or walking, and its metadata is richer, as they are created by people who are intimately familiar with the areas that they are mapping. A map by users for users.

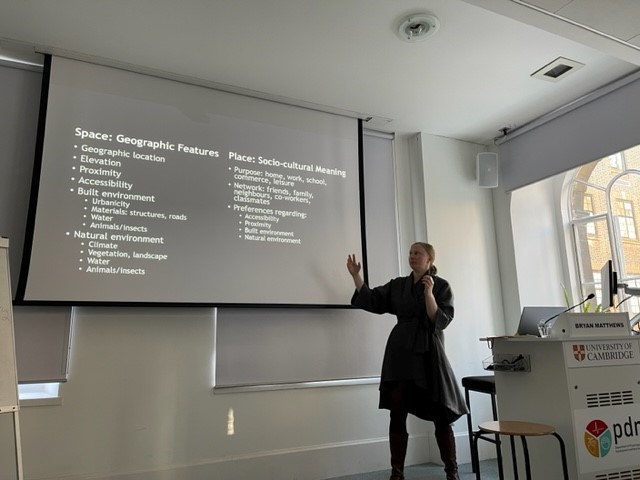

Next up was Dr Rachel Sippy, a Research Associate with the Department of Genetics who presented how geospatial data factored into epidemiological research. In her work, the questions of ‘who’, ‘when’, and ‘where’ a disease outbreak occurred are important, at it is the where that gives her research a geographical focus. Maps, however, are often not detailed enough to provide information about an outbreak of disease among a population or community as maps can only mark out the incident site, the place, whereas the spatial context of that place, which she denotes as space, is equally as important in understanding disease outbreaks.

Of ‘Space’ and ‘Place’: Rachel at the November 2023 Data Champion forum

It can be difficult, however, to understand what a researcher is measuring and what types of data can be used to measure space and/or place. Spatial data, as Rachel pointed out, can be difficult to work with and the researcher has to decide if spatial data is a burden or fundamental to the understanding of a disease outbreak in a particular setting. Rachel discussed several aspects of spatial data which she has considered in her research such as visualisation techniques, data sources and methods of analysis. They all come with their own sets of challenges and researchers have to navigate them to decide how best to tell the fundamental story that answers the research question. This essentially comes down to an act of curation of spatial data, as Rachel pointed out, quoting Mark Monmoneir, that “not only is it easy to lie with maps, it’s essential”. In doing so, researchers working with spatial data would have to navigate the political and cultural hierarchies that are explicitly and implicitly inherent to places, and any ethical considerations relating to both the human and non-human (animal) inhabitants of those geographical locations. Ultimately, how data owners choose to model the spatial data will affect the analysis of the research, and with it, its utility for public health.

After lunch, both Martin and Rachel sat together to hold a combined Q&A session and a discussion emerged around the topic of subjectivity. A question was raised to Rachel regarding mapping and subjectivity, as it was noticed that how she described place, which included socio-cultural meanings and personal preferences of the inhabitants of the place, can be considered to be subjective in manner. Rachel agreed and alluded back to her presentation, where she mentioned that these aspects of mapping can get fuzzy as researchers would have to deal with matters relating to identity, political affiliations and personal opinions, such as how safe an individual may feel in a particular place. Martin added that with the OSM project the data must be objective as possible, yet the maps themselves are subjective views of objective data.

Rachel and Martin answering questions from the Data Champions at the November 2023 forum

Martin also brought to attention that maps are contested spaces because spaces can be political in nature. Rachel added that sometimes, maps do not appropriately represent the contested nature of her field sites, which she only learned through time on the field. In this way, context is very important for “real mapping”. As an example, Martin discussed his “UK collision data” map, created outside the University, which states where collisions have happened, giving the example of one of central Cambridge’s busiest streets, Mill Road: without contextual information such as what time these collisions occurred, what vehicles were involved, and the environmental conditions at the time of the accident, a collision map may not be that valuable. To this end, it was asked whether ethnographic research could provide useful data in the act of mapping and the speakers agreed.