This blog post is part of the write-up of an investigation into the background of people working in scholarly communication, with a specific focus on skills.

Introduction

Library staff need to have a wide range of skills in order to undertake their roles. Whatever type of library they work in and whatever their individual role there is a range of both generic and specialist skills which staff need to acquire over the course of their career. In the Office of Scholarly Communication our focus is on making sure library staff are equipped to work in research support roles but we also have a wider interest in who makes up the global scholarly communication workforce.

In late 2016 we conducted a survey to find out more about this issue. We were slightly overwhelmed by the popularity of the survey which gathered over 500 responses from people who self-identified as working in scholarly communication which we defined as:

The process by which academics, scholars and researchers share and publish their research findings with the wider academic community and beyond. This includes, but is not limited to, areas such as open access and open data, copyright, institutional repositories and research data management.

You can read a summary of some of the findings from this research here but we wanted to delve a little deeper and look at which skills scholarly communication staff felt they needed and how they developed them. This blog post looks at that question.

Which skills?

Rather than come up with yet another list of skills that staff should or could have we made the decision to use an existing list from UKeIG – the UK eInformation Group of CILIP. This list is comprehensive in its coverage and we felt that it would provide a good basis for future comparisons as well as providing a list with which the community would be familiar. The list is of course not exhaustive and respondents were invited to add any additional skills which they felt were relevant to their roles.

Skills for current roles

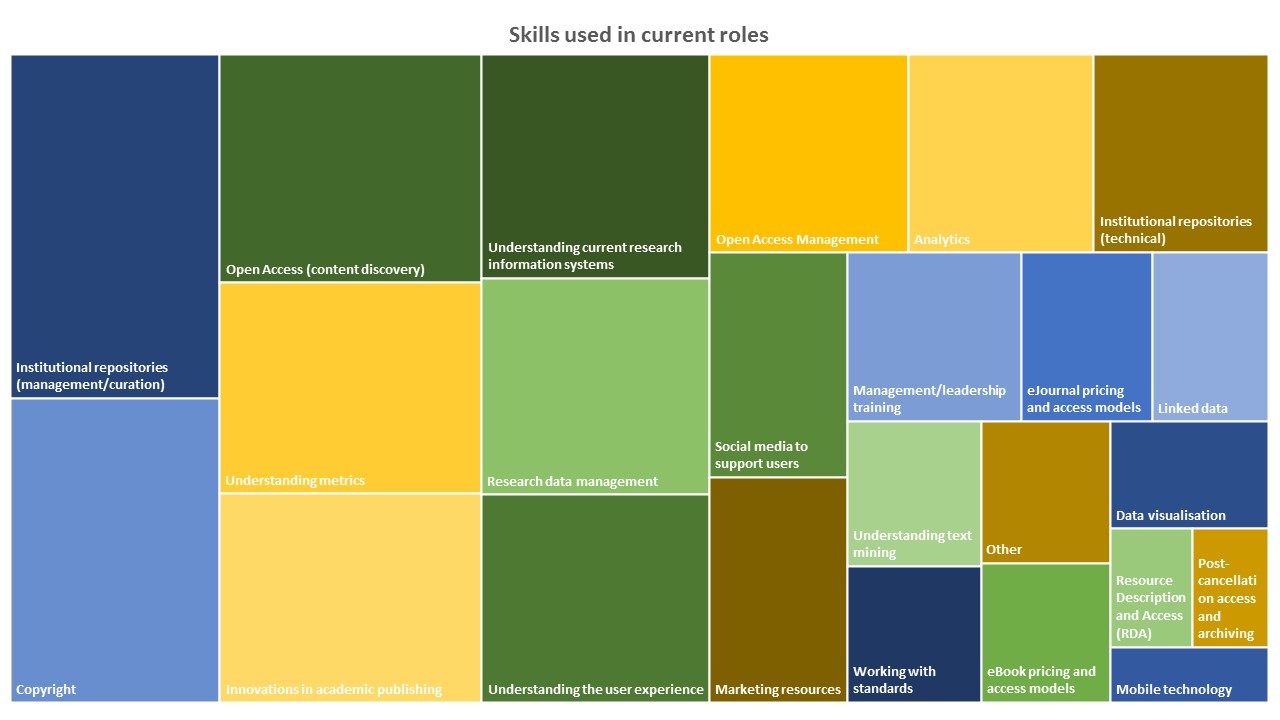

Respondents were asked to highlight the skills which they used in their current roles. Their responses are summarised in Figure 1 (all figures can be viewed at higher resolution by clicking on them).

Figure 1 Skills used in current roles

Institutional repository (management/curation) (72%) and Copyright (63%) were the skills most used, closely followed by Open Access – content discovery (59%) and Understanding metrics (55%).

Some skills were used with much less frequency such as Resource Description and Access (RDA) (10%), Post-cancellation access and archiving (9%) and Mobile technology (8%). Under the option Other skills specified by respondents included knowledge of open educational resources, educating faculty and students about how to get published and electronic theses.

Skills for future roles

Respondents were also asked to select the skills they felt would be important for the future of the profession. The results are summarised in Figure 2:

Figure 2 Future skills

Figure 2 Future skills

The top four selections had a similar number of responses: Innovations in academic publishing (51%), Research data management (50%), Understanding the user experience (47%) and Copyright (46%). It is interesting to note that Copyright is the only skill to appear in the top five of both current and future skills.

The other end of the scale again included RDA (6%) and Post-cancellation access (7%) as well as working with standards (6%). Under the option Other skills included instruction and education, developing strategic partnerships and gumption!

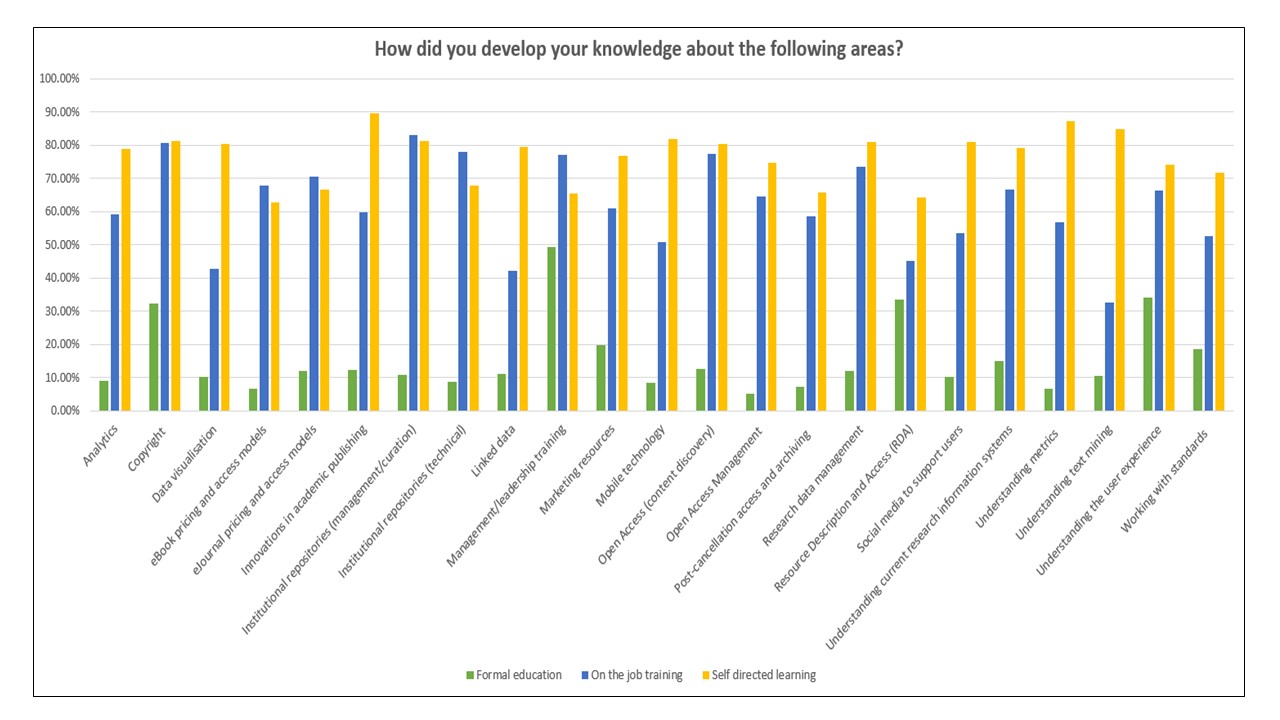

Developing these skills

What we really wanted to know was how people working in scholarly communication developed these skills – through their formal education, on the job training or self-directed learning. Survey respondents were asked how they had developed the skills included on the UKeIG list, and their responses can be seen in Figure 3 below:

Figure 3 Complete skill list

Almost all of the respondents had some level of either undergraduate or postgraduate education, with 71% either holding or working towards a postgraduate qualification in library and information science. Given this, it is surprising to note that so few felt that they had developed the skills they needed for their role through formal education. This gap could perhaps be attributed to the fact that 74% of respondents have held their qualifications for a significant amount of time and so these subjects were not offered at the time. They would have had little choice but to learn these skills on the job or in their own time as it was unlikely to be practical to return to formal education.

Generic skills on the list scored much higher with participants for formal education, perhaps because library school courses are designed to produce well-rounded information professionals able to work in a variety of sectors and so cover the skills that are most likely to be of use in a broad career.

Looking at the results in more detail we can see that a potential skills gap is being created. Looking at the top five skills respondents’ have identified as using in their current role we can see that the levels of formal learning for each are low (Figure 4).

Figure 4 How are current skills developed?

There is evidence that this skills gap could continue into the future. Figure 5 shows the top five skills respondents think will be of most importance to the future of the profession. Again the numbers developing these skills through formal education are low, showing that those working in scholarly communication are having to rely on either on the job or self-directed learning to develop the skills they identify as being important to the future of the profession.

Figure 5 How are future skills developed?

The results of this analysis seem to tie in with previously shared results which showed that just over half of respondents with an LIS qualification (56%) felt that this did not equip them with knowledge of the scholarly communication process.

Next steps

We will continue to analyse the results of the survey to find out more about how those working in scholarly communication have developed their skill sets and how they see future offerings being delivered. In the meantime the OSC is part of a group which is looking to tackle the provision of dedicated scholarly communication in the UK. As well as sharing our discussions on this blog you can talk to us at various events. We have already visited RLUK and are scheduled to present at LILAC and CILIP Careers Day so do come and chat to us if you have a chance!

Excellent insights. May I copy and publish this findings on the weekly bulletin The Librarian Times. The Librarian Times is a weekly volunteer bulletin for library professionals in Bangladesh.

We are delighted you find this useful! Please do copy this and share where you think it will be helpful. All blogs on Unlocking Research are available under a Creative Commons Attribution license which means you can copy and reuse the material as long as you acknowledge the source.

From across the Pond: Glad to see “understanding the user experience” is included. That is especially important for libraries serving hospital clinicians who need to access clinical information in only a few minutes or their question/validation goes unanswered.

Librarians have not used their collective influence to ensure online resource vendors are meeting this need. E Books are mostly only pdfs which are OK for medical students but useless for clinicians. Books not pdfs, are not much of an improvement. For example they have poor displays of results, little enhanced mapping of related terms over and above the book’s index, and few aids to make it easy to back up and start over if a path taken is not fruitful .

Practicing Evidence-Based Medicine is made incredibly difficult due to the number of conflicts of interest authors of books, articles, practice guidelines and online resources have. Yet the big kahuna in the U.S. that is replacing librarians in small community hospitals, UptoDate, no longer puts conflicts of interest in-your-face next to the author’s name for a section, but now has them under a link entitled “contributor disclosures”. It’s competitors don’t even do that.