Let’s not pull any punches here. We are unimpressed. Late last week HEFCE published a blog: Are UK universities on track to meet open access requirements? In the blog HEFCE identified the key issues in meeting OA requirements as:

- The complexity of the OA environment

- Resource constraints

- Cultural resistance to OA

- Inadequate technical infrastructure.

Right. So the deliberate obstruction to Open Access by the academic publishing industry doesn’t factor at all?

Policy confusion

We also note that the fact that the funders have different compliance requirements in terms of the means by which we make work available, the timing in the publication process and the financial support of their policies is not articulated clearly in this list. The euphemism used is ‘complexity’.

Well, yes. To give some idea of how ‘complex’ this situation is, the sister blog to this one describes the decision making process the Cambridge Open Access Team follows to ensure compliance with our multiple policies.

But we are hopeful the impending creation of UK Research and Innovation bringing HEFCE into the same regulatory body as the Research Councils will result in something being done about the conflicting policy problem. Indeed, the survey HEFCE is running may feed into that process.

Publisher obfuscation

However there are no such positive outlooks for the challenges publishers continually throw at us in relation to Open Access.

Elsevier has a long and complicated list of embargoes. There is a different list for embargoes imposed in the UK to those for the rest of the world. The complications of a range of embargo periods and some journals with non-standard arrangements are apparent on both Wiley’s and Taylor & Francis’ pages. BMJ has a non-compliant special embargo of 12 months for funders that require archiving of articles. There is no embargo at all for non-funded papers.

An exemplar is Springer with a standard embargo of 12 months for everything. However, because we are signed up to the Springer Compact most of our publications are published Open Access anyway.

We are not alone in our irritation. In the last couple of months there have been two publications identifying the amount of work libraries do to manage embargoes for Open Access compliance.

The University of St Andrews published a UKCORR blog on 22 August. Requesting permission: reflections and perspectives from the University of St Andrews discussed the processes they have to manage to ensure compliance with publishers which don’t have a public Open Access or author self-archiving policy. The reason this is a challenge is because 60% of their permissions requests are for outputs potentially in scope for the REF open access policy. St Andrews notes that “having an effective permissions policy can potentially affect an institution’s approach to their REF return and level of exceptions required.”

Management of poor publisher practices in relation to Open Access is not a UK specific problem. In July, Leila Sterman, scholarly communication librarian at Montana State University published an article in College and Research Libraries News – The enemy of the good: How specifics in publisher’s green OA policies are bogging down IR deposits. In the article she argued that there is no consistency in policies and embargoes, which creates unnecessary work. She states that publishers, “who often claim they are supportive of green open access, work to impose restrictions on digital works as if they were physical items being placed in physical locations.”

Sterman also refers to the same challenges identified by St Andrews, noting that: Green open access policies are often buried on publisher’s websites or only mentioned in contracts. This practice obfuscates important information, increasing both the time library staff spend searching for that information and author’s obliviousness to the opportunities and restrictions of green open access.

Indeed this is not a new issue. Over four years ago in a previous role and different country, I published a post: Walking in quicksand – keeping up with copyright agreements which notes similar issues as these two recent papers, but also identifies the issue of publishers changing their policies without notice.

Do we need embargoes?

Publishers argue that they need embargoes to remain ‘sustainable’. The claim is that by making an author’s copy of the work (not copyedited or formatted) available in a repository on a relatively piecemeal basis will cause libraries to cancel subscriptions en masse. Despite repeated attempts, to date there has been no evidence released to support this claim.

The UK produces 6% of the world’s research output. And yet when the RCUK policy was announced some publishers (see here and here) changed their policies across the globe to take advantage of the huge amounts of UK government funds being added into the system.

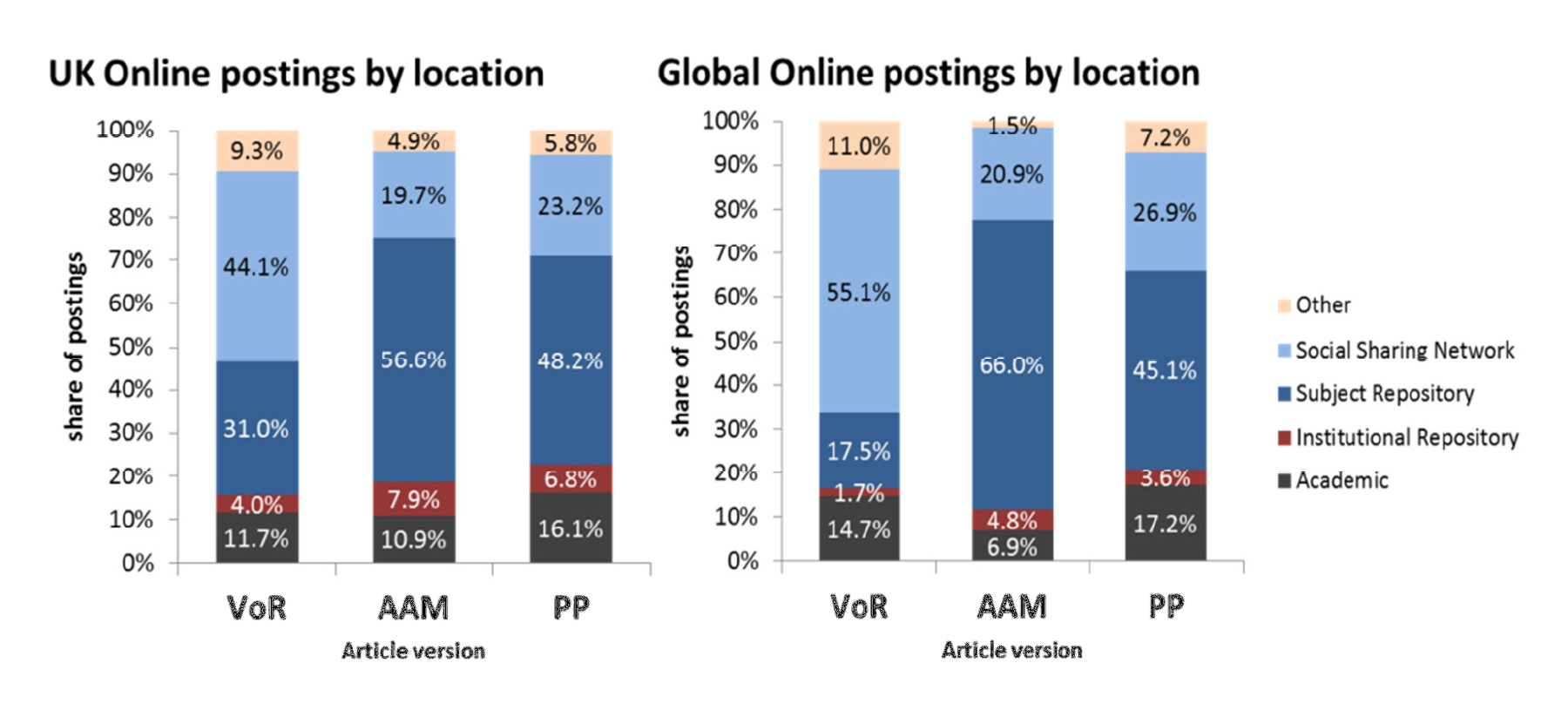

As an aside, the green = cancellation argument does beg the question about the value publishers themselves place on the work they do between an Author’s Accepted Manuscript and the final Version of Record. If access to the AAM is apparently good enough for libraries to cancel subscriptions then why bother doing the extra work?

See also my UKSG eNews editorial with comments on OA support from a small research institute perspective

https://www.uksg.org/sites/uksg.org/files/Editorial403.pdf