In the blog post “It’s hard getting a date (of publication)”, Maria Angelaki discussed how a seemingly straightforward task may turn into a complicated and time-consuming affair for our Open Access Team. As it turns out, it isn’t the only one. The process of identifying the version of a manuscript (whether it is the submitted, accepted or published version) can also require observation and deduction skills on par with Sherlock Holmes’.

Unfortunately, it is something we need to do all the time. We need to make sure that the manuscript we’re processing isn’t the submitted version, as only published or accepted versions are deposited in Apollo. And we need to differentiate between published and accepted manuscripts, as many publishers – including the biggest players Elsevier, Taylor & Francis, Springer Nature and Wiley – only allow self-archiving of accepted manuscripts in institutional repositories, unless the published version has been made Open Access with a Creative Commons licence.

So it’s kind of important to get that right…

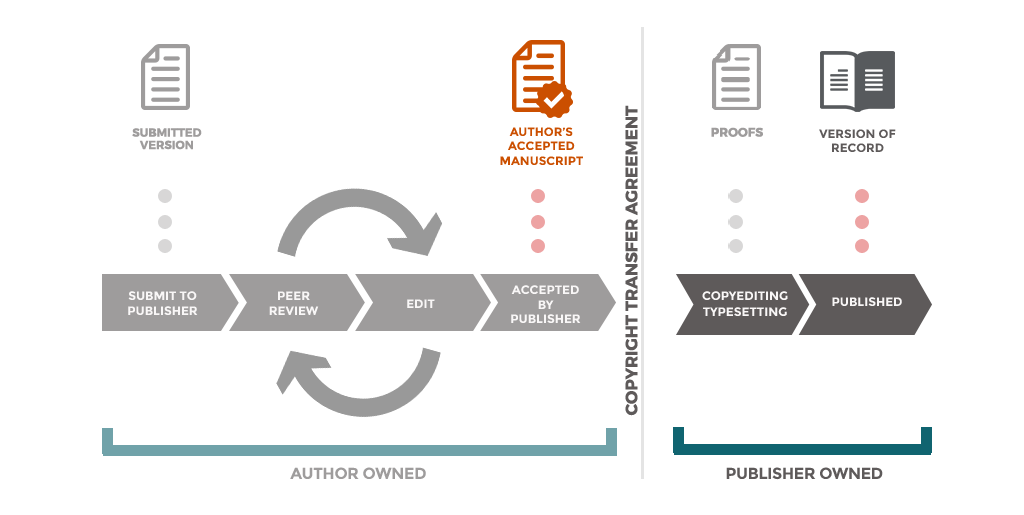

Explaining manuscript versions

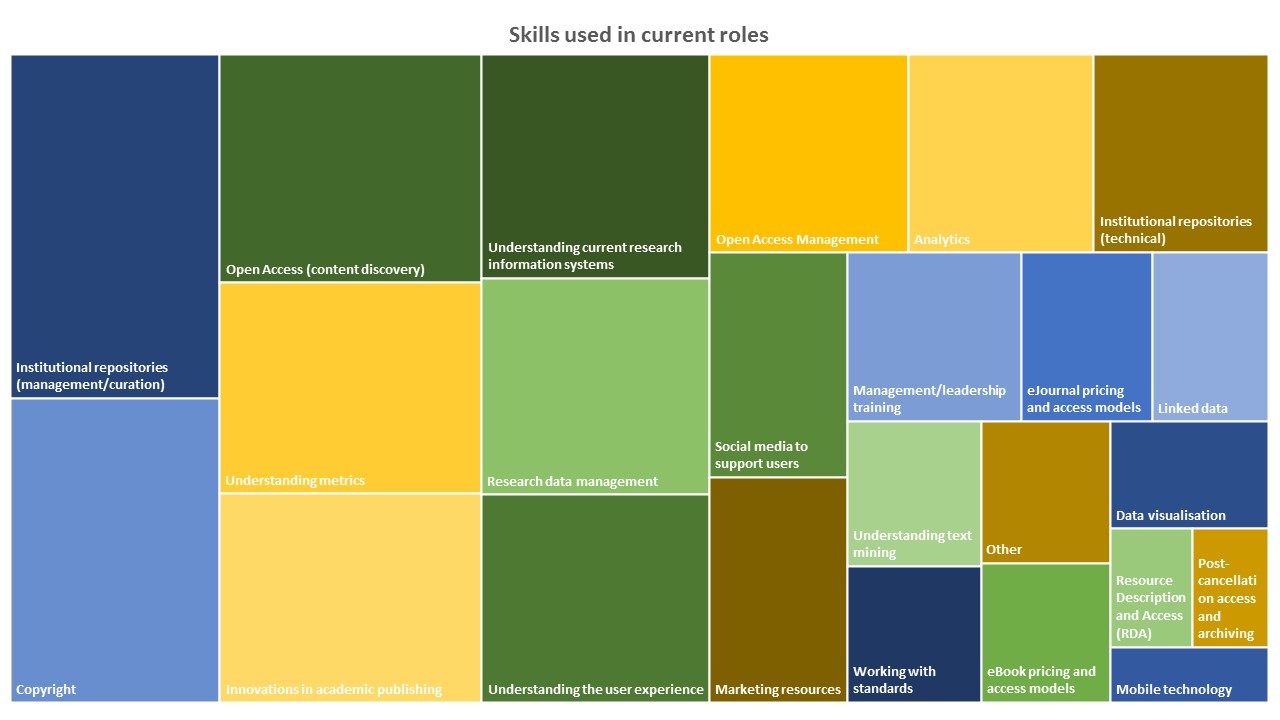

Manuscripts (of journal articles, conference papers, book chapters, etc.) come in various shapes and sizes throughout the publication lifecycle. At the onset a manuscript is prepared and submitted for publication in a journal. It then normally goes through one or more rounds of peer-review leading to more or less substantial revisions of the original text, until the editor is satisfied with the revised manuscript and formally accepts it for publication. Following this, the accepted manuscript goes through proofreading, formatting, typesetting and copy-editing by the publisher. The final published version (also called the version of record) is the outcome of this. The whole process is illustrated below.

Identifying published versions

So the published version of a manuscript is the version… that is published? Yes and no, as sometimes manuscripts are published online in their accepted version. What we usually mean by published version is the final version of the manuscript which includes the publisher’s copy-editing, typesetting and copyright statement. It also typically shows citation details such as the DOI, volume and page numbers, and downloadable files will almost invariably be in a PDF format. Below are two snapshots of published articles, with citation details and copyright information zoomed in. On the left is an article from the journal Applied Linguistics published by Oxford University Press and on the right an article from the journal Cell Discovery published by Springer Nature (click to enlarge any of the images).

Published versions are usually obvious to the eye and the easiest to recognise. In a way the published version of a manuscript is a bit like love: you may mistake other things for it but when you find it you just know. In order to decide if we can deposit it in our institutional repository, we need to find out whether the final version was made Open Access with a Creative Commons (CC) licence (or in rarer cases with the publisher’s own licence). This isn’t always straightforward, as we will now see.

Published Open Access with a CC licence?

When an article has been published Open Access with a CC licence, a statement usually appears at the bottom of the article on the journal website. However as we want to deposit a PDF file in the repository, we are concerned with the Open Access statement that is within the PDF document itself. Quite a few articles are said to be Open Access/CC BY on their HTML version but not on the PDF. This is problematic as it means we can’t always assume that we can go ahead with the deposit from the webpage – we need to systematically search the PDF for the Open Access statement. We also need to make sure that the CC licence is clearly mentioned, as it’s sometimes omitted even though it was chosen at the time of paying Open Access charges.

The Open Access statement will appear at various places on the file depending on the publisher and journal, though usually either at the very end of the article or in the footer of the first page as in the following examples from Elsevier (left) and Springer Nature (right).

A common practice among the Open Access team is to search the file for various terms including “creative”, “cc”, “open access”, “license”, “common” and quite often a combination of these. But even this isn’t a foolproof method as the search may retrieve no result despite the search terms appearing within the document. The most common publishers tend to put Open Access statements in consistent places, but others might put them in unusual places such as in a footnote in the middle of a paper. That means we may have to scroll through a whole 30- or 40-page document to find them – quite a time-consuming process.

Identifying accepted versions

The accepted manuscript is the version that has gone through peer-review. The content should be the same as the final published version, but it shouldn’t include any copy-editing, typesetting or copyright marking from the publisher. The file can be either a PDF or a Word document. The most easily recognisable accepted versions are files that are essentially just plain text, without any layout features, as shown below. The majority of accepted manuscripts look like this.

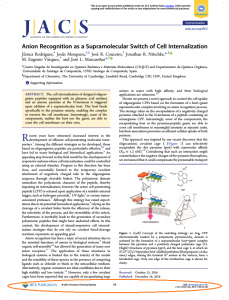

However sometimes accepted manuscripts may at first glance appear to be published versions. This is because authors may be required to use publisher templates at the submission stage of their paper. But whilst looking like published versions, accepted manuscripts will not show the journal/publisher logo, citation details or copyright statement (or they might show incomplete details, e.g. a copyright statement such as © 20xx *publisher name*). Compare the published version (left) and accepted manuscript (right) of the same paper below.

As we can see the accepted manuscript is formatted like the published version, but doesn’t show the journal and publisher logo, the page numbers, issue/volume numbers, DOI or the copyright statement.

So when trying to establish whether a given file is the published or accepted version, looking out for the above is a fairly foolproof method.

Identifying submitted versions

This is where things get rather tricky. Because the difference between an accepted and submitted manuscript lies in the actual content of the paper, it is often impossible to tell them apart based on visual clues. There are usually two ways to find out:

- Getting confirmation from the author

- Going through a process of finding and comparing the submission date and acceptance date of the paper (if available), mostly relevant in the case of arXiv files

Getting confirmation from the author of the manuscript is obviously the preferable and time-saving option. Unfortunately many researchers mislabel their files when uploading them to the system, describing their accepted/published version file as submitted (the fact that they do so when submitting the paper to us may partly explain this). So rather than relying on file descriptions, having an actual statement from the author that the file is the submitted version is better. Although in an ideal world this would never happen as everyone would know that only accepted and published versions should be sent to us.

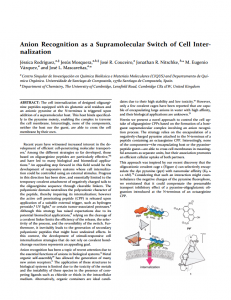

A common incarnation of submitted manuscripts we receive is arXiv files. These are files that have been deposited in arXiv, an online repository of pre-prints that is widely used by scientists, especially mathematicians and physicists. An example is shown below.

Clicking on the arXiv reference on the left-hand side of the document (circled) leads to the arXiv record page as shown below.

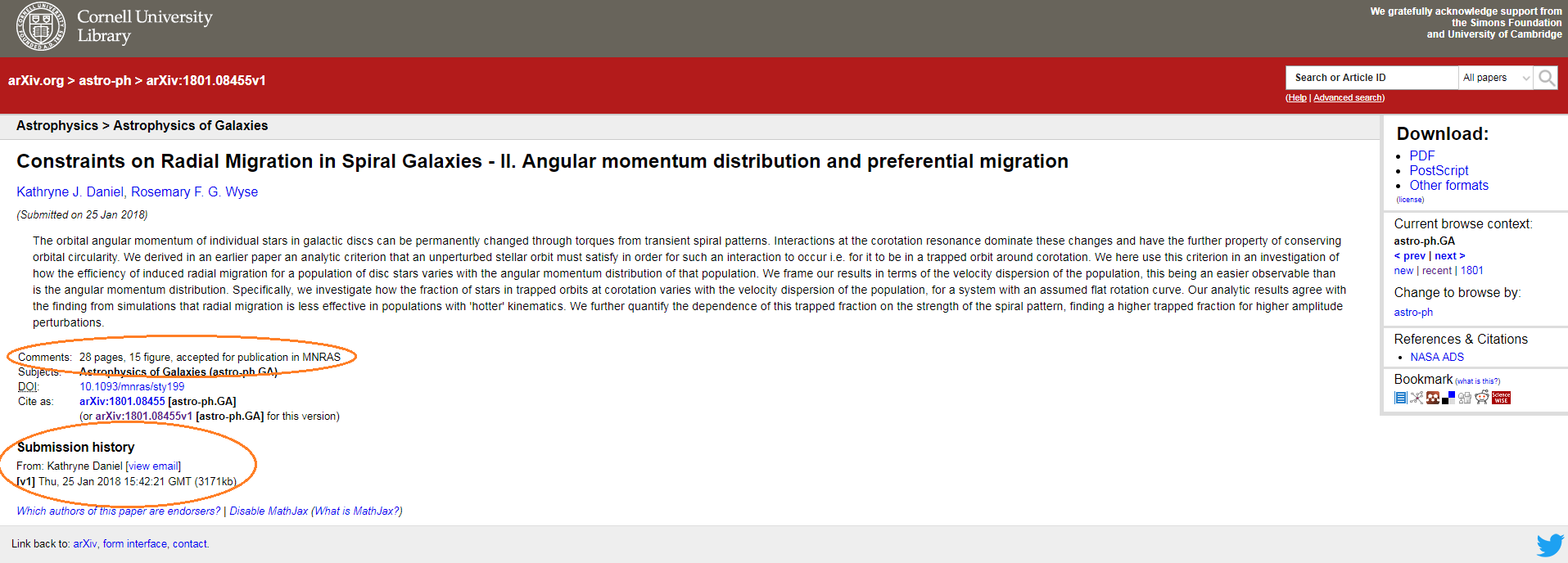

The ‘comments’ and ‘submission history’ sections may give clues as to whether the file is the submitted or accepted manuscript. In the above example the comments indicate that the manuscript was accepted for publication by the MNRAS journal (Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society). So this arXiv file is probably the accepted manuscript.

The submission history lists the date(s) on which the file (and possible subsequent versions of it) was/were deposited in arXiv. By comparing these dates with the formal acceptance date of the manuscript which can be found on the journal website (if published), we can infer whether the arXiv file is the submitted or accepted version. If the manuscript hasn’t been published and there is no way of comparing dates, in the absence of any other information, we assume that the arXiv file is the submitted version.

Conclusion

Distinguishing between different manuscript versions is by no means straightforward. The fact that even our experienced Open Access Team may still encounter cases where they are unsure which version they are looking at shows how confusing it can be. The process of comparing dates can be time-consuming itself, as not all publishers show acceptance dates for papers (ring a bell?).

Depositing a published (not OA) version instead of an accepted manuscript may infringe publisher copyright. Depositing a submitted version instead of an accepted manuscript may mean that research that hasn’t been vetted and scrutinised becomes publicly available through our repository and possibly be mistaken as peer-reviewed. When processing a manuscript we need to be sure about what version we are dealing with, and ideally we shouldn’t need to go out of our way to find out.