Are research institutions engaging their researchers with Research Data Management (RDM)? And if so, how are they doing it? In this post, Rosie Higman (@RosieHLib), Research Data Advisor, University of Cambridge, and Hardy Schwamm (@hardyschwamm), Research Data Manager, Lancaster University explore the work they are doing in their respective institutions.

Whilst funder policies were the initial catalyst for many RDM services at UK universities there are many reasons to engage with RDM, from increased impact to moving towards Open Research as the new normal. And a growing number of researchers are keen to get involved! These reasons also highlight the need for a democratic, researcher-led approach if the behavioural change necessary for RDM is to be achieved. Following initial discussions online and at the Research Data Network event in Cambridge on 6 September, we wanted to find out whether and how others are engaging researchers beyond iterating funder policies.

At both Cambridge and Lancaster we are starting initiatives focused on this, respectively Data Champions and Data Conversations. The Data Champions at Cambridge will act as local experts in RDM, advocating at a departmental level and helping the RDM team to communicate across a fragmented institution. We also hope they will form a community of practice, sharing their expertise in areas such as big data and software preservation. The Lancaster University Data Conversations will provide a forum to researchers from all disciplines to share their data experiences and knowledge. The first event will be on 30 January 2017.

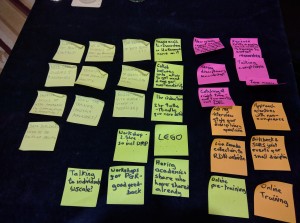

Having presented our respective plans to the RDM Forum (RDMF16) in Edinburgh on 22nd November we ran breakout sessions where small groups discussed the approaches our and other universities were taking, the results summarised below highlighting different forms that engagement with researchers will take.

Having presented our respective plans to the RDM Forum (RDMF16) in Edinburgh on 22nd November we ran breakout sessions where small groups discussed the approaches our and other universities were taking, the results summarised below highlighting different forms that engagement with researchers will take.

Targeting our training

RDM workshops seem to be the most common way research data teams are engaging with researchers, typically targeting postgraduate research students and postdoctoral researchers. A recurrent theme was the need to target workshops for specific disciplinary groups, including several workshops run jointly between institutions where this meant it was possible to get sufficient participants for smaller disciplines. Alongside targeting disciplines some have found inviting academics who have experience of sharing their data to speak at workshops greatly increases engagement.

As well as focusing workshops so they are directly applicable to particular disciplines, several institutions have had success in linking their workshop to a particular tangible output, recognising that researchers are busy and are not interested in a general introduction. Examples of this include workshops around Data Management Plans, and embedding RDM into teaching students how to use databases.

An issue many institutions are having is getting the timing right for their workshops: too early and research students won’t have any data to manage or even be thinking about it; too late and students may have got into bad data management habits. Finding the goldilocks time which is ‘just right’ can be tricky. Two solutions to this problem were proposed: having short online training available before a more in-depth training later on, and having a 1 hour session as part of an induction followed by a 2 hour session 9-18 months into the PhD.

Tailored support

Alongside workshops, the most popular way to get researchers interested in RDM was through individual appointments, so that the conversation can be tailored to their needs, although this obviously presents a problem of scalability when most institutions only have one individual staff member dedicated to RDM.

There are two solutions to this problem which were mentioned during the breakout session. Firstly, some people are using a ‘train the trainer’ approach to involve other research support staff who are based in departments and already have regular contact with researchers. These people can act as intermediaries and are likely to have a good awareness of the discipline-specific issues which the researchers they support will be interested in.

There are two solutions to this problem which were mentioned during the breakout session. Firstly, some people are using a ‘train the trainer’ approach to involve other research support staff who are based in departments and already have regular contact with researchers. These people can act as intermediaries and are likely to have a good awareness of the discipline-specific issues which the researchers they support will be interested in.

The other option discussed was holding drop-in sessions within departments, where researchers know the RDM team will be on a regular basis. These have had mixed success at many institutions but seem to work better when paired with a more established service such as the Open Access or Impact team.

What RDM services should we offer?

We started the discussion at the RDM Forum thinking about extending our services beyond sheer compliance in order to create an “RDM community” where data management is part of good research practice and contributes to the Open Research agenda. This is the thinking behind the new initiatives at Cambridge and Lancaster.

However, there were also some critical or sceptical voices at our RDMF16 discussions. How can we promote an RDM community when we struggle to persuade researchers being compliant with institutional and funder policies? All RDM support teams are small and have many other tasks aside from advocacy and training. Some expressed concern that they lack the skills to market our services beyond the traditional methods used by libraries. We need to address and consider these concerns about capacity and skill sets as we attempt to engage researchers beyond compliance.

Summary

It is clear from our discussions that there is a wide variety of RDM-related activities at UK universities which stretch beyond enforcing compliance, but engaging large numbers of researchers is an ongoing concern. We also realised that many RDM professionals are not very good at practising what we preach and sharing our materials, so it’s worth highlighting that training materials can be shared on the RDM training community on Zenodo as long as they have an open license.

Many thanks to the participants at our breakout session at the RDMForum 16, and Angus Whyte for taking notes which allowed us to write this piece. You can follow previous discussions on this topic on Gitter.

Published on 30 November

Written by Rosie Higman and Hardy Schwamm