When I was just settling in to the world of open access and scholarly communication, I wrote about the need for open access to stop being a fringe activity and enter the mainstream of researcher behaviour:

“Open access needs to stop being a ‘fringe’ activity and become part of the mainstream. It shouldn’t be an afterthought to the publication process. Whether the solution to academic inaction is better systems or, as I believe, greater engagement and reward, I feel that the scholarly communications and repository community can look forward to many interesting developments over the coming months and years.”

While much has changed in the five years since I (somewhat naïvely) wrote those concluding thoughts, there are still significant barriers towards the complete opening of scholarly discourse. However, should open access be an afterthought for researchers? I’ve changed my mind. Open access should be something researchers don’t even need to think about, and I think that future is already here, though I fear it will ultimately sideline institutional repositories.

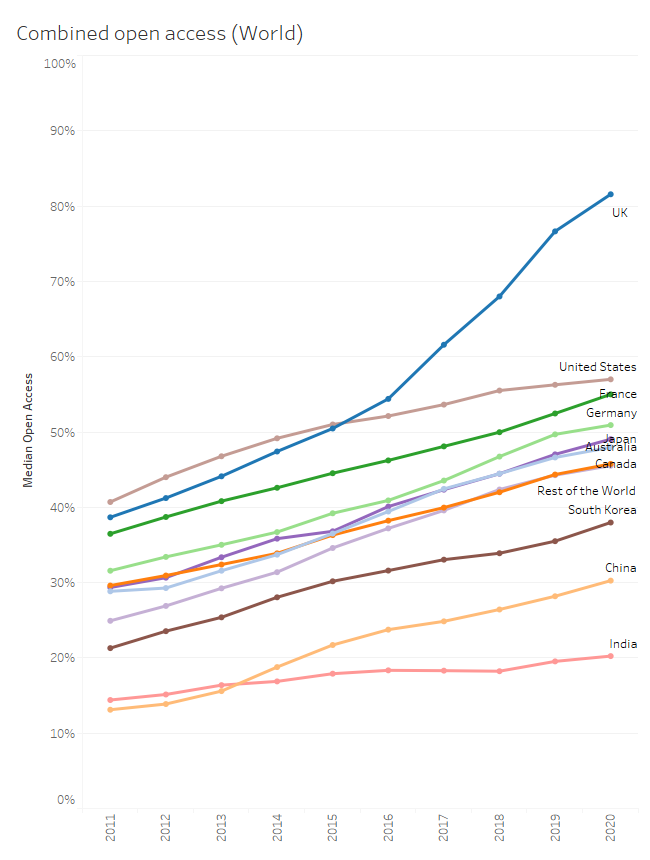

According to the 2020 Leiden Ranking, the median rate at which UK institutions make their research outputs open access is over 80%, which is far higher than any other nation (Figure 1). Indeed, the UK is the only country that has ‘levelled up’ over the last five years, while the rest of the world’s institutions have slowly plodded along making slow, but steady, progress.

Figure 1. The median institutional open access percentage for each country according to the Leiden Ranking. Note, these figures are medians of all institutions within a country. This does not mean that 80% of the UK’s publications are open access, but that the median rate of open access at UK institutions is 80%.

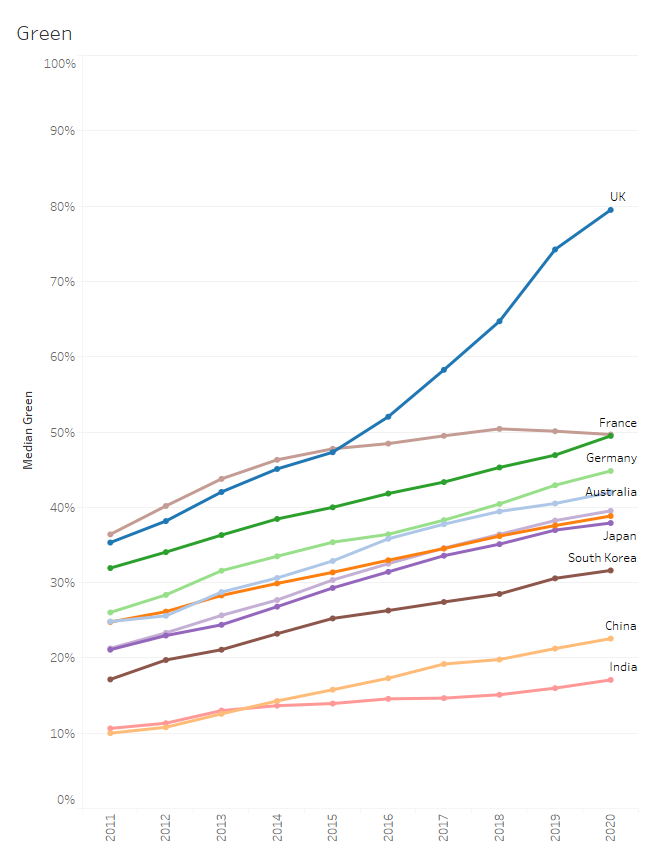

The main driver for this increase in open access content in the UK is through green open access (Figure 2), due in large part to the REF 2021 open access policy (announced in 2014 and effective from 2016). This is a dramatic demonstration of the influence that policy can have on researcher behaviour, which has made open access a mainstream activity in the UK.

Figure 2. The median institutional green open access percentage for each country according to the Leiden Ranking.

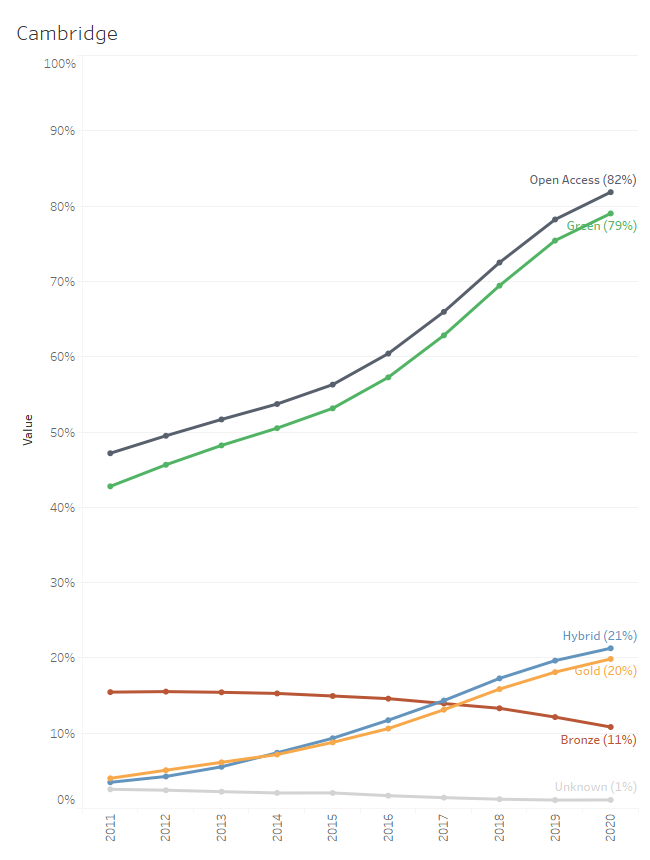

Like the rest of the UK, Cambridge has seen similar trends across all forms of open access (Figure 3), with rising use of green open access, and steadily increasing adoption of gold and hybrid. Yet despite all the money poured into gold and (more controversially) hybrid open access, the net effect of all this other activity is a measly 3% additional open access content (82% vs 79%). Which begs the question, was it worth it? If open access can be so successfully achieved through green routes, what is the inherent benefit of gold/hybrid open access?

Figure 3. Open access trends in Cambridge according to the Leiden Ranking. In the 2020 ranking, 79% was delivered through green open access. This means that despite all the work to facilitate other forms of open access, this activity only contributed an additional 3% to the total (82%).

Of course, Plan S has now emerged as the most significant attempt to coordinate a clear and coherent international strategy for open access. While it is not without its detractors, I am nonetheless supportive of cOAlition S’s overall aims. However, as the UK scholarly communication community has experienced, policy implementation is messy and can lead to unintended consequences. While Plan S provides options for complying through green open access routes, the discussions that institutions and publishers (both traditional and fully open access alike) have engaged in are almost entirely focussed on gold open access through transformative deals. This is not because we, as institutions, want to spend more on publishing, but rather it is the pragmatic approach to create open access content at the source and provide authors with easy and palatable routes to open access. It also is a recognition that flipping journals requires give and take from institutions and publishers alike.

We are now very close to reaching a point where open access can be an afterthought for researchers, particularly in the UK. In large part, it will be done for them through direct agreements between institutions and publishers. Cambridge already has open access publishing arrangements with over 5000 journals, and this figure will continue to grow as we sign more transformative agreements. However, this will ultimately be to the detriment of green open access. Instead of being the only open access source for a journal article, institutional repositories will instead become secondary storehouses of already gold open access content. The heyday of institutional repositories, if one ever existed, is now over.

For me, that is a sad thought. We have poured enormous resource and effort into maintaining Apollo, but we must recognise the burden that green open access places on researchers. They have better things to do. I expect that the next five years will see a dramatic increase in gold and hybrid open access content produced in the UK. Green open access won’t go away, but we will have entered a time where open access is no longer fringe, nor indeed mainstream, but rather de facto for all research.

Published 23 October 2020

Written by Dr Arthur Smith