Five research papers and five traditional stories were combined during Cambridge Science Festival in March 2018 to make Tales of Discovery.

Five research papers and five traditional stories were combined during Cambridge Science Festival in March 2018 to make Tales of Discovery.

The session was aimed at families, to show them that there is a world of research available to the general public stored on Apollo, the University’s repository – and it’s all cool stuff.

It was also aimed at researchers, to get them thinking about new ways to make their research available to a general public – including uploading their research on to the Apollo repository.

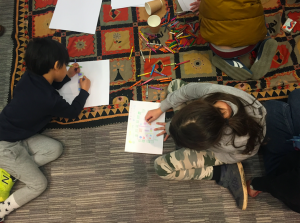

At the end of each story the audience were challenged to interpret the stories and research in their own way.

Here’s what happened during the morning.

Labour Pains: Scenes of Birth and Becoming in Old Norse Legendary Literature

The research

Kate Olley’s article looks at the drama of childbirth as depicted in Old Norse legendary literature. This article made a great beginning to the session, because it looks into the power of story to give an insight into the past. Childbirth stories are fascinating and informative because they are such important moments – ‘moments of crisis’ not just for an individual but for a whole society. They show so much about a culture, from the details of everyday life, to a picture of a society’s values and structure. Also, unlike stories of great battles and adventures, they put women and everyday life at the centre of the story.

The story

I retold one of the stories from Kate’s article, ‘Hrolf and the elvish woman’ from the saga of Hrolf the Walker. An elvish woman summons Hrolf, a king who has fallen on hard times, to help her daughter who is under a curse. She has been in labour for 19 days, but cannot give birth unless she is touched by human hands.

I retold one of the stories from Kate’s article, ‘Hrolf and the elvish woman’ from the saga of Hrolf the Walker. An elvish woman summons Hrolf, a king who has fallen on hard times, to help her daughter who is under a curse. She has been in labour for 19 days, but cannot give birth unless she is touched by human hands.

Kate pointed out some things the story shows us: the extreme danger of childbirth in those times; and the way a birth changes everybody’s role. The woman becomes a mother, but the fortunes of Hrolf the midwife are also changed for ever.

The challenge

We talked about how people still tell childbirth stories, and they often have the same mythic resonances as old Icelandic saga. Is there a story you tell your children about when they were a baby? (or a story that your parents tell you?)

Revolutionising Computing Infrastructure for Citizen Empowerment

The research

Noa Zilberman explains that almost every aspect of our lives today is being digitally monitored: from our social networks activity, through online shopping habits to financial records. Can new technology enable us to choose who holds this data? Her research, based on highly technical computer engineering, addresses a social issue that Noa feels passionate about. I chose a story that was a metaphor for her research, with a hero taking on the might of a huge and greedy dragon.

The story

I based the story on the epic account of Beowulf fighting the dragon, which reflected Noa’s passion and how important she felt the issues raised by her research are to society in general. But, as is the way with story, more links emerged during the telling. The flickering flames of the dragon’s cave, reflected the heat emitted by internet server farms. The ease with which a thief can steal gold from the hoard, and the potential harm this can do, proved highly topical. When the hero asks the blacksmith to make a shield of metal to protect him from the dragon’s breath, Noa produced her secret weapon: a programmable board, not more than six inches long, which enables data to be moved more efficiently by individual computers.

The challenge

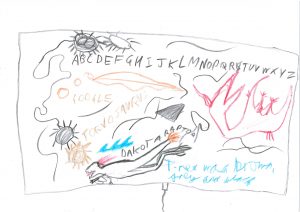

It can be hard to visualise what ‘the internet’ really is. What might an ‘internet dragon’ look like? Can you draw one?

The provenance, date and significance of a Cook-voyage Polynesian sculpture

The research

Trisha Biers paper sheds light on the shifting sands of anthropological investigation. It has a particular Cambridge link: she uncovers the secrets of a wooden carving brought back from Captain Cook’s voyage to the Pacific in the 18th Century. The mysterious carving – of two figures and a dog – is now the logo of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

The story

As I searched for a Polynesian story about two men and a dog, I discovered many of the same factors that Trisha highlights. Stories travel across the Pacific Ocean just as commerce, people, and artworks do, making it hard to pinpoint the source of the story.

The story I chose, about the deity/hero Maui, turning his annoying brother-in-law, Irawaru, into the first dog, fits only partially – just like the many theories about the carving. Stories about Maui are known all over Polynesia: but the trickster Maui from New Zealand, where this story comes from, is different from the godlike Maui of Tahiti, the carving’s likely provenance. Like the carving, the stories of Maui have travelled to the Western world, in films like Moanna, as well as to Cambridge. Stories, which can’t be carbon-dated like the carving, shift and change just like the dog Irawaru.

The challenge

Not knowing the true story can set our imaginations free! I asked the audience to draw or write their own story about two men and a dog.

Treated Incidence of Psychotic Disorders in the Multinational EU-GEI Study

The research

Hannah Jongsma’s research looks at the risk of developing a psychotic disorder, which for a long time was thought to be due to genetics. She finds that it is influenced by many factors – both genetic and environmental – for example the risk is higher in young men and ethnic minorities.

The story

I paired the story with a sinister little tale from Grimm, Bearskin, about an outsider who is rejected by society because of his wild appearance – he wears the unwashed skin of a ferocious bear and lives like a wild man. It touched the issues of Hannah’s research at many points. The hero is a rootless and penniless young man far from home – a situation identified as high-risk in Hannah’s study. His encounter with a wild bear with whom he swaps coats is the stuff of hallucination. Like psychosis, in Hannah’s view, the problem is partly one of the way society views the outsider. And, as in Hannah’s study, being accepted by a family and given emotional support is a protection against psychosis. The remarkable thing about this this wonder-tale, so far removed from reality, was how it opened up a wide-ranging conversation about the research. Its far-fetched images helped us explore the issues of real-life research. Hannah was surprised that her research could be re-envisioned and presented in such a different way.

The challenge

Using the ideas from Hannah’s paper, suggest an alternative ending to the story.

Determining the Molecular Pathology of Inherited Retinal Disease

The research

Crina Samarghitean shows how bioinformatics tools help researchers find new genes, and doctors find diagnosis in difficult disorders. Her article looks at better treatment and quality of life for patients with primary immunodeficiencies, and focuses on inherited retinal disease which is a common cause of visual impairment.

The story

The story of the telescope, the carpet and the lemon turned out to be a celebration of the possibilities of medical research with bioinformatics. Three brothers search for the perfect gift to win the heart of the princess, and find that these three magical objects allow them to save her life. This piece of research was the first one I tried to find a story for, and it seemed to be the hardest to translate into non-specialist language, until Crina said ‘I see the research as a quest for treasure: someone who has looked everywhere for a cure for their illness comes to this data-bank, and it’s like a treasure chest with the answer to their problem.’

The challenge

Crina is already committed to the idea that the arts can be used to interpret science. She has made artworks inspired by the gene sequences she has been working on. The challenge was to make pictures inspired by Crina’s paintings and models.