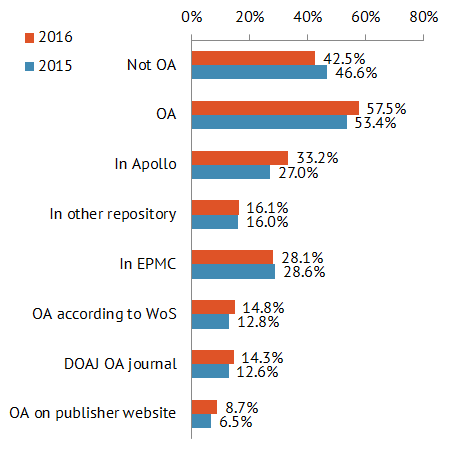

Today, Research England released Monitoring sector progress towards compliance with funder open access policies the results of a survey they ran in August last year in conjunction with RCUK, Wellcome Trust and Jisc.

Cambridge University was one of the 113 institutions that answered a significant number of questions about how we were managing compliance with various open access policies, what systems we were using and our decision making processes. Reading the collective responses has been illuminating.

The rather celebratory commentary from UKRI has focused on the compliance aspect – see the Research England’s press release: Over 80% of research outputs meet requirements of REF 2021 open access policy and the post by the Executive Chair of Research England David Sweeney, Open access – are we almost there for REF?

What’s it all about?

At risk of putting a dampener on the party I’d like to point a few things out. For a start, compliance with a policy is not the end goal of a policy in itself. While clearly the UK policies over the past five years have increased the amount of UK research that is available open access, we do need to ask ourselves ‘so what?’.

What we are not measuring, or indeed even discussing, is the reason why we are doing this.

While the open access policies of other funders such as Wellcome Trust and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation articulate the end goal: “foster a richer research culture” in the former and “ information sharing and transparency” in the latter, the REF2021 policy is surprisingly perfunctory. It simply states: “certain research outputs should be made open-access to be eligible for submission to the next Research Excellence Framework”.

It would be enormously helpful to those responsible for ‘selling’ the idea to our research community if there were some evidence to demonstrate the value in what we are all doing. A stick only goes so far.

It’s really hard, people

Part of the reason why we are having so much difficulty selling the idea to both our research community and the administration of the University is because open access compliance is expensive and complicated, as this survey amply demonstrates.

While there may have been an idea that requiring the research community to provide their work on acceptance would mean they would become more aware and engaged with Open Access, it seems this has not been achieved. Given that 71% of HEIs reported that AAMs are deposited by a member of staff from professional services, it is safe to say the past six years since the Finch Report have not significantly changed author behaviour.

With 335 staff at 1.0FTE recorded as “directly engaged in supporting and implementing OA at their institution”, it is clear that compliance is a highly resource hungry endeavour. This is driving the decision making at institutional level. While “the intent of funders’ OA policies is to make as many outputs freely available as possible”, institutions are focusing on the outputs that are likely to be chosen for the REF (as opposed to making everything available).

I suspect this is ideology meeting pragmatism. Not only can institutions not support the overall openness agenda, these policies seem to be further underlining the limited reward systems we currently use in academia.

The infrastructure problem

The first conclusion of the report was that “systems which support and implement OA are largely manual, resource-intensive processes”. The report notes that compliance checking tools are inadequate partly because of the complexity of funder policies and the labyrinth that is publisher embargo policies. It goes on to say the findings “demonstrate the need for CRIS systems, and other compliance tools used by institutions be reviewed and updated”.

This may the case, but buried in that suggestion is years of work and considerable cost. We know from experience. It has taken us at Cambridge 2.5 years and a very significant investment to link our CRIS system (Symplectic Elements) to our DSpace repository Apollo. And we are still not there in terms of being able to provide meaningful reports to our departments.

Who is paying for all of this?

When we say ‘open’…

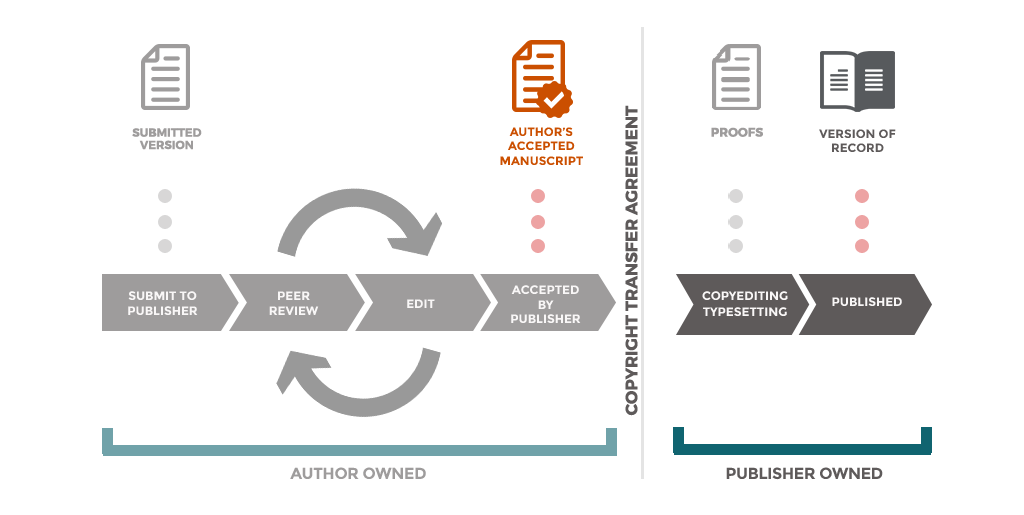

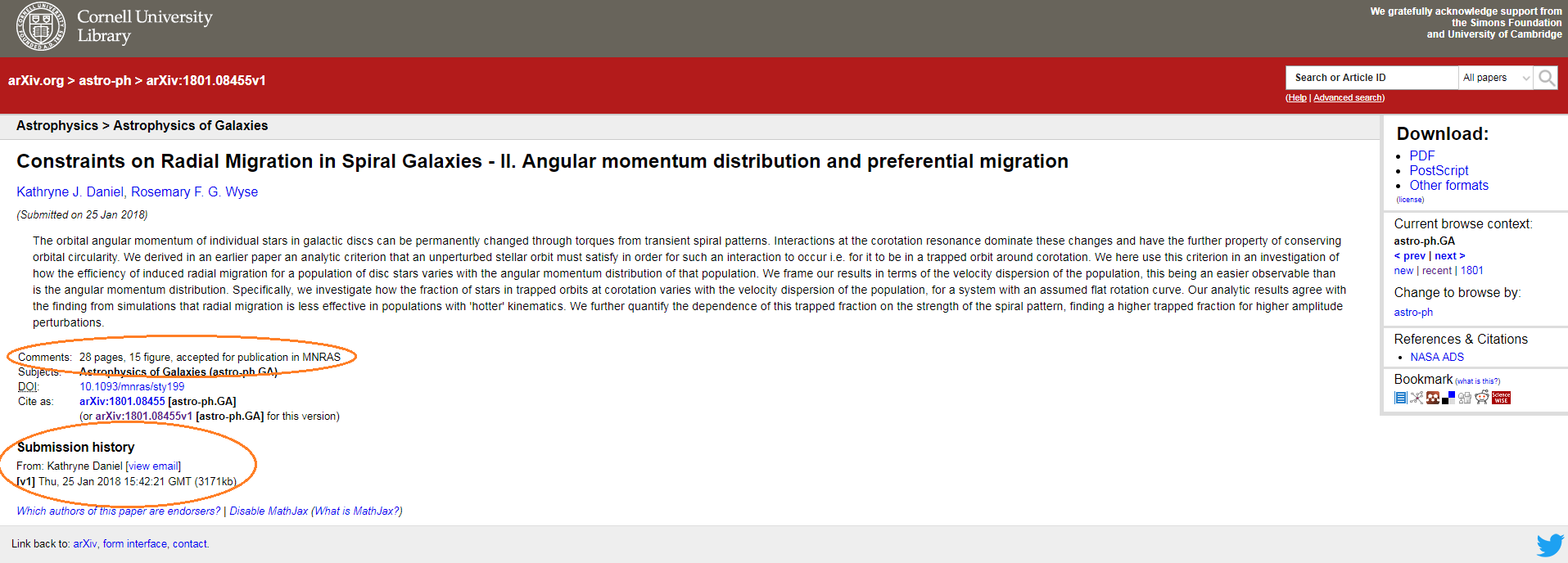

The report touches on what is a serious problem in the process. Because we are obtaining works at time of acceptance (an aspect of the policy Cambridge supports), and embargo periods cannot be set until the date of publication is known, there is a significant body of material languishing under indefinite embargoes waiting to be manually checked and updated.

The report notes that ‘there is no clear preference…as to how AAMs are augmented or replaced in repositories following the release of later versions’. Given the lack of any automated way of checking this information the problem is unmanageable without huge human intervention.

At Cambridge we offer a ‘Request a Copy’ service which at least makes the works accessible, but this is an already out of control situation that is compounding as time progresses.

Solutions?

We really need to focus on sector solutions rather than each institution investing independently. Indeed, the second last conclusion is that ‘the survey has demonstrated the need for publishers, funders and research institutions to work towards reducing burdensome manual processes”. One such solution, which has a sole mention in the report, is the UK Scholarly Communication Licence as a way of managing the host of licences.

Right at the end of the report in the second last point something very true to my heart was mentioned: “Finally, respondents highlighted the need for training and skills at an institutional level to ensure that staff are kept up to date with resources and tools associated with OA processes.” Well, yes. This is something we have been trying to address at a sector level, and the solutions are not yet obvious.

This report is an excellent snapshot and will allow institutions such as ours some level of benchmarking. But it does highlight that we have a long way to go.