During International Data Week 2016, the Office of Scholarly Communication is celebrating with a series of blog posts about data. The first post was a summary of an event we held in July. This post looks at the challenges associated with financially supporting RDM training.

The problem

There is a desperate need for training in research data management. Our significant engagement with researchers at the University of Cambridge over the past 18 months has indicated to us that research data cannot be effectively shared if it has not been properly managed during the research lifecycle. Researchers cannot be expected to share their data at the end of their research project if they are unable to locate their data, if the data is not correctly labelled or if it lacks metadata to make the data re-usable. We have stated that on several occasions, including our response to the draft UK Concordat on Open Research Data which was released in its final form on the 28th July this year.

To test whether our beliefs were in-line with researchers’ needs, last year we conducted a short survey on research data management needs among our academic community. Of those responding, 94% of researchers indicated that it would be ‘useful’ or ‘very useful’ to have workshops on research data management (see our earlier blog post for the full discussion of the survey results). In response to this we developed a 1.5 hour introductory workshop to research data management and started delivering this to researchers in Cambridge in July 2015.

Train early, train often

Our workshops have evolved substantially since the initial sessions, through responses to the feedback we collect. The workshops are now considerably improved, not only more interactive, but also have been extended to 2.5 hours to allow time to provide more practical examples of good data management.

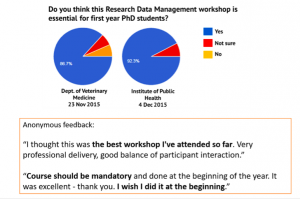

The feedback from our workshops was overwhelmingly positive. As a result, many departments identified research data management skills as core competencies needed by every PhD student and asked us to deliver our workshops as part of their compulsory training for PhD students. This is fantastic news for both our team and the awareness of RDM at Cambridge, and we have therefore accepted all these individual requests.

But sometimes you can be a little too successful. We recently received another request from the Graduate School of Life Sciences to make our workshop compulsory for all their PhD students. While this is great news, there are 400 new PhD students every year at the Graduate School of Life Sciences. The maximum capacity at our workshop is 20 attendees, which means we would need to deliver 20 workshops throughout the year to cover this cohort. And when we consider the Graduate School of Life Sciences is one of five schools accepting PhD students in Cambridge, we need to look at how we would respond if other schools approached us with similar requests.

Another issue is that while our improved workshop on research data management covered the basic research data management needs, researchers have told us they need more in-depth discipline-specific training. We recognise this, and do try to provide training that is directed at the audience – a challenge when we need to serve all researchers across the University – from arts and humanities through social and life sciences, to medical research and particle physics (and many, many other disciplines).

So we have identified a broad need for RDM training, a specific need for training for PhD students as they begin their research, as well as discipline-specific support for all researchers. But there are only two staff members in the Research Data Team who can deliver RDM training, and delivering training is only one of many tasks which we need to undertake for the Research Data Facility to function. We simply do not have the capacity to meet this obvious need. After discussion we have agreed to deliver four workshops out of the requested 20 for the Graduate School of Life Sciences and to reconsider the situation in the summer break next year.

The plan – Data Champions

We have begun to think both about how we can meet RDM training needs given current staff capacity and how we can link the experts in different aspects of data management that we know exist around the University of Cambridge. There is already an active OpenCon Cambridge group which promotes the benefits of Open Access, Open Data and Open Education; but we wanted to focus on all aspects of RDM.

We have started to develop the idea of having Data Champions in each department, institute or college who can act as the local experts as well as delivering some discipline-specific training to their community. This has the advantage of increasing the number of trainers across the University, making the workshops tailored to the relevant audience, and building a community of experts.

The University of Cambridge is not alone in facing this problem and the several other universities are pursing, or already have, Data Champions in some form. The idea was recently discussed on both Jisc RDM mailing lists and at the Research Data Network meeting which was held at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge last week. At this meeting several different models were proposed, including a national network of champions who could advocate within disciplines at a senior level.

Whilst a national network of champions would be great in the long term we still have an immediate problem within the University of Cambridge and so we have launched a Call for Data Champions to help us raise awareness and increase the amount of training available. The call is open until 17th October and we would welcome any research or support staff or research student with an interest in RDM. There will be support available in learning how to deliver RDM training, a template workshop provided, the opportunity to influence the future of RDM services and a website built to showcase our Data Champions.

We hope to bring all the Data Champions together towards the end of the Michaelmas term so they can start delivering workshops in 2017. We hope to foster a community of experts who can share their knowledge with each other and the Research Data Team so we are in a better position to support our researchers.

The future

The community of Data Champions we hope to bring together at Cambridge will begin to ameliorate some of the problems we are facing with regards to RDM training. However, we will still struggle with staff capacity and at some point researchers will need to be appropriately rewarded for sharing data and supporting others to do the same, a theme of our recent Open Research discussion event.

So we have a temporary solution, and one which we hope will significantly improve the RDM training available at Cambridge, but the issue will not be solved until the underlying incentives for sharing data, publications and all the other research outputs have been addressed.

Published 14 September 2016

Written by Rosie Higman and Dr Marta Teperek