‘More cash, more clarity and don’t make this compulsory’ is the take home message from a recent workshop held with Cambridge researchers on the question of Open Research.

The recent session, called “An Open Future? How Cambridge is Responding to Challenges in the Open Landscape” was with a group of new Cambridge lecturers at a seminar organized by Pathways in Higher Education Practice. This event offered us an opportunity to go beyond the usual information we provide in our training workshops*.

This session provided a unique opportunity to speak with researchers from various disciplines further along in their career who already had a basic knowledge of Open Access and Research Data sharing requirements. This meant we were able to have more of an informed discussion rather than a lecture and we wanted to hear what they thought about Open Research.

(* The OSC is often asked to provide training on all things Open Research. Generally our training is focused on PhD students and early career researchers. We create our PowerPoint slides that explain the benefits of Open Access, the necessity of a good Data Management Plan or how to promote your research through social media (all of which are freely available here). We try to make these sessions as interactive as possible.)

Quiz Time

The session started by laying out how the current academic publishing model works. Basically, researchers submit their latest findings to a journal for FREE, peer reviewers review the paper for FREE, editors oversee the journal for FREE and the publishers format the article then turn around and charge libraries exorbitant subscription fees (yep, that about sums it up). This got a good laugh from the audience.

So our first activity was a short quiz. We were interested to know if researchers knew how much things cost. We asked them a set of questions:

- How much do you think we pay in subscription costs every year?

- What’s the average APC?

- How many papers were made gold OA and had at least one Cambridge author on it in 2016?

There was a lot of debate among the groups. Some of the answers were wildly overestimated (one researcher suggested £50 million GBP for subscriptions per year), others were quite low.

What are people sharing?

For our next activity, we wanted to know what they were already sharing and what tools they were using to share. We presented each table with a Venn diagram and a bunch of post-its:

Unsurprisingly, the ‘Publication’ circle had the most post-its. Answers included tools such as ArXiv, ResearchGate, and Academia.edu as well as personal websites and Facebook. There were also mentions of Cambridge Open Access and the Departmental Libraries. Interestingly a few noted that they made their work available to researchers through personal contact such as email requests.

There were a few post-its in the ‘Data’ circle describing what tools they used to deposit, such as university repositories and Zenodo.

The ‘Other’ category mostly talked about sharing code and software through github; although, one lecturer noted free workshops they offered. There was only one post-it that made it into the centre and that was for “webpage”. For the future, it may be interesting to know which discipline the researchers were from when they were posting because this theme came up quite a few times during the discussions.

When are people prepared to share?

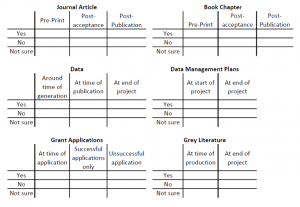

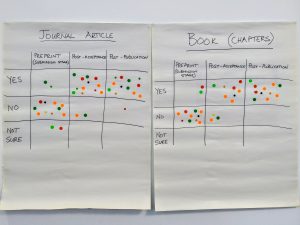

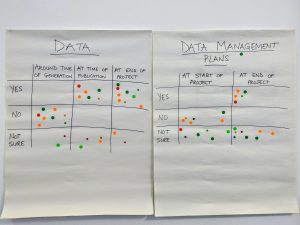

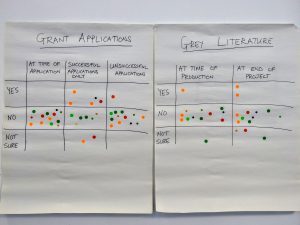

The second activity involved lots of sticky dots and large pieces of paper. The participants were asked if they were comfortable sharing different aspects of their research at different stages in the research lifecycle. Each sheet was laid out in a grid as follows:

All of the researchers were asked to stick dots in the grid. The results were interesting. Most researchers were happy to share the published version of their paper, but a large number were uncomfortable sharing their pre-print or submitted version. There were only two dots in the “yes” square to share pre-prints. During the discussion it was apparent that this was probably down to the culture of the discipline where one physics researcher said it was part of the process versus one of the lecturers from English who disliked having more than one version of her paper available to read. The Book Chapter had similar results.

Data and Data Management Plans were all over the place. There were quite a few dots in the ‘Not sure’ squares. Most were happy to share data at the time of publication or at the end of the project. For the Data Management Plans it was evenly split between ‘yes’ to sharing at the end of the project versus ‘not sure’. No one wanted to share their DMP at the start of the project. There was some confusion among researchers (mostly from the humanities) who felt they didn’t have any data and therefore there was nothing to share.

The majority of the researchers were unenthusiastic about sharing their Grant Applications or Grey literature at any stage. For Grant Applications the overall feeling was that if the grant was successful then researchers didn’t want to share their methodology. If the grant was unsuccessful, they were reluctant to share their failures or they planned to submit to another granting agency. Most lecturers in the room agreed that they were fine sharing an abstract of their grant awards (which many funders post on their website).

As for Grey Literature which we defined as working papers or opinion papers, no one wanted to share anything that could be considered unfinished or not well thought out. One member of the law faculty said that if they had produced any grey literature worth sharing, then they would publish it in a journal. Moreover, it could be detrimental to their career if they shared anything that wasn’t well-researched and presented.

More money please

To finish up the session, we asked researchers what more could the University be doing to promote Open Research. Not surprisingly most people were resistant to any University mandate telling them what to do. In addition, they were strongly against any Open Research requirements being tied in with HR practices like promotions. The researchers supported discipline specific requirements for Open Research.

Clearer instructions from the University and from funders of what is required of researchers was also desired. Having a myriad of policies is quite confusing and burdensome for researchers who already feel pressured to publish. In the end, most said that if the University would pay, then they would be happy to share their published work.