As part of Open Access Week 2016, the Office of Scholarly Communication is publishing a series of blog posts on open access and open research. In this final OAWeek post Dr Arthur Smith analyses how much Cambridge research is openly available.

For us in the Office of Scholarly Communication it’s important that, as much possible, the University’s research is made Open Access. While we can guarantee that research deposited in the University repository Apollo will be made available in one way or another, it’s not clear how other sources of Open Access contribute to this goal. This blog is an attempt to quantify the amount of Cambridge research that is openly available.

In mid-August I used Cottage Labs’ Lantern service in an attempt to quantify just how open the University’s research really is. Lantern uses DOIs, PMIDs or PMCIDs to match publications in a variety of sources such as CORE and Europe PMC, to determine the Open Access status of a publication – it will even try to look at a publisher’s website to determine an article’s Open Access status. This process isn’t infallible, and it relies heavily on DOI matching, but it provides a good insight into the possible sources of Open Access material.

attempt to quantify just how open the University’s research really is. Lantern uses DOIs, PMIDs or PMCIDs to match publications in a variety of sources such as CORE and Europe PMC, to determine the Open Access status of a publication – it will even try to look at a publisher’s website to determine an article’s Open Access status. This process isn’t infallible, and it relies heavily on DOI matching, but it provides a good insight into the possible sources of Open Access material.

To determine the base list of publications against which the analysis could be run, I queried Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus to obtain a list of publications attributed to Cambridge authors. In 2015, the University published 9069 articles, reviews and conference papers according to Web of Science. Scopus returned a slightly lower figure of 7983 publications. Combining these two publication lists, and filtering to only include records with a DOI, produced one master list of 9714 unique publications (that’s ~26 publications/day!).

In 2015 the Open Access team processed 2746 HEFCE eligible submissions, so naïvely speaking, the University achieved a 28.3% HEFCE compliance rate. That’s not bad, especially because the HEFCE policy had not yet come into force, but what about other Open Access sources? We know that other universities in the UK are also depositing papers in their repositories, and some researchers make their work ‘gold’ Open Access without going through the Open Access team, so the total amount of Open Access content must be higher.

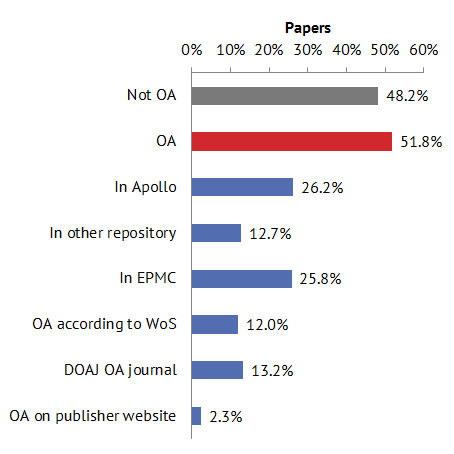

In addition to the Lantern analysis, I also exported all available DOIs from Apollo and matched these to the DOIs obtained from WoS/Scopus. WoS also classifies some publications as being Open Access, and I included these figures too. If a publication was found in at least one potentially Open Access source I classified it as Open Access. Here are the results:

It is pleasing that our naïve estimate of 28.3% HEFCE compliance closely matches the number of records found in Apollo (26.2%). The discrepancy is likely due to a number of factors, including publications received by the Open Access Team that were actually published in 2014 or 2016, but submitted in 2015, and Apollo records that don’t have a publisher DOI to match against. However, the most important point to note is the overall open access figure – in 2015 more than 50% of the University’s scholarly publications with a DOI were available in at least one “open access” source.

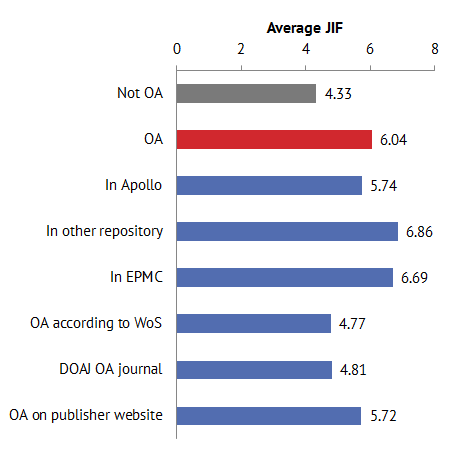

Let’s dig a little deeper into the analysis. Using everyone’s favourite metric, the journal impact factor (JIF), the average JIF of articles in Apollo was 5.74 compared to 4.33 for articles that were not OA. Other repositories and Europe PMC achieved even higher average JIFs. On average, Open Access publications by Cambridge authors have a higher JIF (6.04) than articles that are not OA, which suggests that researchers are making value judgements on what to make Open Access based on journal reputation. If a paper appears in a low(er) impact journal, it’s less likely to be made Open Access. Anecdotally this is something we have experienced at Cambridge.

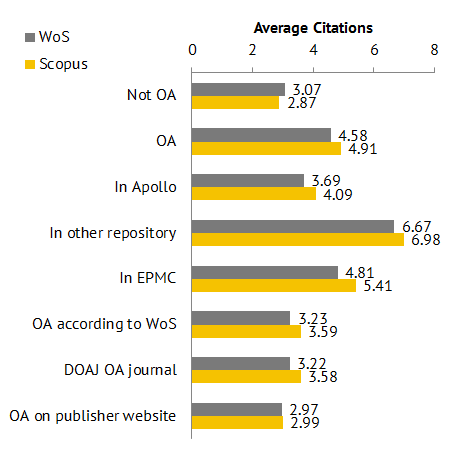

The WoS and Scopus exports contain citation information at the article level, so we can also look at direct citations received by these publications (up to 16 August 2016) rather than relying on the JIF. I found that Open Access articles, on average, received 1.5 to 2 more citations than articles that are not Open Access. However, is this because authors are making their higher impact articles Open Access (which one might expect to receive more citations anyway) and are not bothering with the rest? Or this is effect due entirely to the greater accessibility offered by Open Access publication? Could the differences arise because of different researcher behaviour across different disciplines?

My feeling is that we have reached a turning point – the increased citation rates of Open Access material is not caused by the article being Open Access as these articles would have naturally received more citations anyway. Instead of looking at formal literature citations, the benefits of Open Access need to be measured outside of academia in areas that would not contribute to an articles citations.

Breaking it down by the source of Open Access reveals that articles that appear in other repositories receive significantly more citations than any other source. This potentially reveals that collaborative papers between researchers at different institutions are likely to have greater impact than papers conducted solely at one institution (Cambridge), however, a more thorough analysis that looks at author affiliations would be needed to confirm this.

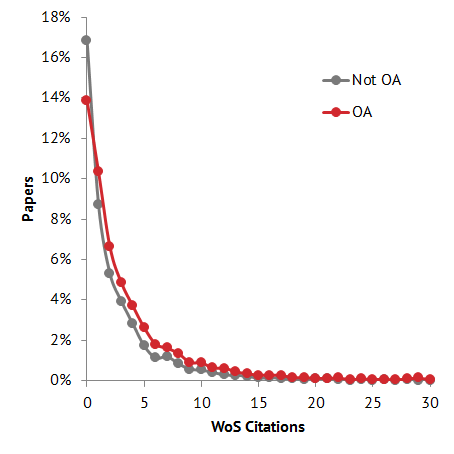

If we focus on the WoS citation distribution the difference in average citations becomes clearer. Of 8348 WoS articles, not only are there fewer Open Access articles with no citations (14% vs 17%), but Open Access articles also receive more citations in general.

What can we take away from this analysis? Firstly, Lantern is a valuable tool for discovering other sources of Open Access content. It identified over a thousand articles by Cambridge researchers in other institutional repositories that we did not know existed. When it comes time for the next REF, these other repositories may prove a vital lifeline in determining whether a paper is HEFCE compliant.

Secondly, more than 50% of the University’s 2015 research publications are potentially Open Access. Hopefully a similar analysis of 2016’s papers will show that even more of the University’s research is Open Access this year. And finally, although Open Access articles receive more citations than articles that are not Open Access, it is no longer clear whether this is caused by the article being Open Access, disciplinary differences, or if authors are more likely to make their best work Open Access.

Published 28 October 2016

Written by Dr Arthur Smith