There has been much discussion recently about the reproducibility crisis and about the growing distrust among the public in the quality of research. As illustrated in our ‘Case for Open Research’ series of blog posts, one of the main reasons for this is that researchers are currently rewarded for the number of papers they publish in high impact factor journals, and not necessarily for the quality of work that they are doing.

Indeed, Cambridge researchers clearly indicated that the lack of incentives to do anything other than publishing in these types of journals is one of the main blockers discouraging them from adopting a more open research practice.

Joining forces with the Wellcome Trust

The Office of Scholarly Communication started talking about these problem with the Open Research team at the Wellcome Trust. The Wellcome Trust are natural allies, as they have consistently led their researchers towards greater openness. They were one of the first funding bodies to introduce policies on Open Access and on data management and sharing. Now the Wellcome Trust is moving towards proactively supporting Open Research beyond enforcing their compliance requirements.

To promote immediate and transparent research sharing, they have recently launched the Wellcome Open Research platform which allows researchers to submit articles about virtually any research output and get published within a couple of days. The Wellcome Trust is now considering making Open Research one of their strategic priorities.

We quickly realised that we have a lot of shared interests, and joining forces to tackle the problem together made a lot of sense. We came up with the idea to launch the Open Research Pilot Project.

The Open Research Pilot – understanding the barriers to “openness”

We conceived the project as a two year experiment, which would allow us to gain an understanding of what is needed for researchers to share and get credit for all outputs of the research process. These include non-positive results, protocols, source code, presentations and other research outputs beyond the remit of traditional publications.

The Project aims to understand the barriers preventing researchers from sharing (including resource and time implications), as well as what the incentives are. The Project aims to utilise the new Wellcome Open Research publishing platform, together with other channels, to share these outputs.

The invitation to take part in the Pilot was sent to all researchers at Cambridge funded by the Wellcome Trust. Participating researchers had to commit to sharing of research outputs beyond traditional publications and to engage with the Project, by participating in Project meetings and contributing to Project publications.

Is ‘doing the right thing’ enough incentive?

Our biggest question was whether anyone would be willing to participate in the Pilot. We did not offer any incentive other than encouraging researchers to contribute to the greater good. The only support available to those who wanted to take part in the project was that offered by the Wellcome Trust and Cambridge Open Research team members, but there was no financial aid available to prospective participants. We thought that regardless of the outcome, that inviting researchers would be a good exercise to go through – we thought that if no one applied, we would have learnt that doing ‘the right thing’ was not a good enough motivator.

Thankfully, we received several fantastic applications from individual researchers and research groups who demonstrated great interest in and motivation for Open Research. We initially planned to work with two research groups, but given the quality of applications received and passion for Open Research expressed by the applicants, we decided to extend the scope of the project to four research groups. We have selected researchers doing different types of research, with the aim of learning about distinct problems in sharing that are experienced in diverse research disciplines:

- Dr Laurent Gatto –is doing computational biology research, with a special focus on proteomics data. His interest is: How to effectively share research data and the code needed to reproduce them?

- Dr David Savage – is researching molecular pathogenesis of the consequences of obesity. His question is: What are the problems with sharing data coming from human participants?

- Dr Benjamin Steventon – is a developmental biologist generating and analysing large-scale imaging datasets. He would like to know: Are there image repositories allowing one to share large image datasets in a re-usable way?

- Dr Marta Costa and Dr Greg Jefferis (and others) – researchers leading the work on two collaborative projects: Connectomics and Virtual Fly Brain, which will create interactive tools to interrogate Drosophila neural network connections. They would like to understand: What are the issues with sharing complex interactive datasets? How to ensure long-term preservation of complex digital objects?

Motivations

So what motivated these researchers to apply for the project? We asked this question at the application stage and were positively surprised by the altruistic answers that we received. Our researchers were largely driven by a desire to improve the research process. We have seen responses like:

- “Openness in research, from data and software to publication, is a central pillar of good research.”

- “I am very concerned (disappointed as a scientist) by the current wave of ‘unreproducible’ and/or ‘irrelevant’ research, and am very passionate about contributing to improving scientific endeavour in this regard.”

- “I am very enthusiastic about exploiting new ways of sharing my research output beyond the established peer-review journal system.”

- “I believe that sharing research outputs fully, including data and code are essential to accelerate research, and I have benefitted from it in my own research.”

Summarising, researchers expressed a great desire for contributing to a cultural change. Researchers wanted to change the way in which research was disseminated and to increase research transparency and reproducibility.

Let’s get to work

We all met (the researchers, Wellcome Trust and Cambridge Open Research teams) on Friday 27 January to officially start the two year project. Each research group was appointed a facilitator – a dedicated member of the Cambridge Open Research team to support researchers during the Project. Research groups will meet with their facilitators on a monthly basis in order to discuss shareable research outputs and to decide on best ways to disseminate these outputs. Every six months all project members will meet together to discuss the barriers to sharing discovered and to assess the progress of the Project.

One of the main goals of the Project is to learn what the barriers and incentives are for Open Research and to share these findings with others interested in the subject to inform policy development. Therefore, we will be regularly publishing blog posts on the Unlocking Research blog and on the Wellcome Open Research blog with case studies describing what we have discovered while working together. There will be an update from each research group every six months. We will also be publicly sharing all main outputs of the Project.

We are all extremely excited about going “Open” and we suggest that anyone interested in the Open Research practice watches this space.

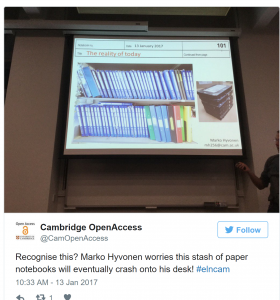

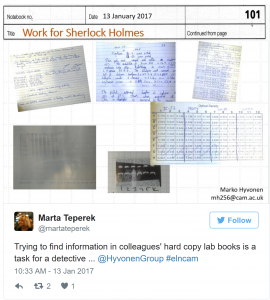

Marko Hyvönen (Dept of Biochemistry)

Marko Hyvönen (Dept of Biochemistry)