As anyone who administers an institutional repository can tell you, repeatedly looking up journals’ policies and attributes is a pain in the neck. We have discussed this problem a few times, noting in 2017 the complex embargo situation and the confusion about publication dates. Indeed it has been clear since 2013 that this is so complicated it is unrealistic to expect researchers to navigate this situation. This means considerable amounts of repository staff time are typically spent traversing a confusing landscape of complex, inconsistent and fluid policies.

To stop or at least mitigate this pain, wouldn’t it be great if those policies and attributes were available in a structured, machine-readable format, so that the burden of retrieving and using such information could be transferred from people to repository software?

(Given, an even better solution would be, of course, for publishers to have simpler and standardised policies across their journals, but there is little indication that this will happen any time soon – see links above.)

Our solution – Orpheus

JISC are currently working on and will shortly release version 2 of their SHERPA services, which have enormous potential for providing machine-readable data on embargo periods and at least some of the other attributes we need. However, circa two years ago we decided that, in face of increasing demand for our services, we could not afford a wait to automate our workflows. Besides, we reasoned that any external solution would be unlikely to cover all the journal attributes we rely on beyond embargo periods, and to be updated at the frequency we require.

So, in the last trimester of 2017, I set out to develop a database that could store in a strictly structured and machine-readable format all bits of information from journals, publishers and conferences that we repeatedly look up. This would replace the time the team behind Cambridge’s DSpace repository Apollo was spending retrieving and manually applying those data to each deposited item.

Orpheus (named after the son of Apollo in Greek mythology) was thus born in January 2018. To mark its first birthday, we have just turned Orpheus into an Open Source project and released the code at https://github.com/osc-cam/orpheus.

In this blog post, I will provide an overview of Orpheus’ main features and of how we have been using it to increase the efficiency of our repository and services.

Supported attributes and available interfaces

On the web interface for editors and users, attributes are listed, for each journal, publisher and conference, in a detailed view that looks like this:

On the web interface for editors and users, attributes are listed, for each journal, publisher and conference, in a detailed view that looks like this:

Orpheus currently supports the following attributes of journals/publishers:

- name, synonyms, URL and, for journals, ISSNs and publisher

- revenue model (subscription, hybrid, fully Open Access)

- gold OA policy (article processing charges, licence choices, etc)

- green OA policy (allowed versions and outlets, embargo period, licence, etc)

- Europe PMC participation (whether or not the journal deposits papers in EPMC)

- deals/discounts (whether the journal is included in an institutional deal such as Springer Compact or offers any discounts)

- contacts (e-mail addresses for queries

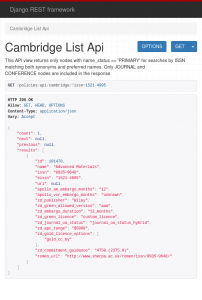

Orpheus’ RESTful API exposes journal attributes in JSON format and its response can be tailored to facilitate integration with repositories platforms and other systems. For instance, the screenshot below shows only the attributes that we feed into Apollo and/or our helpdesk system (on the left below).

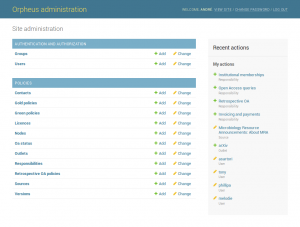

Like every project written in Django, Orpheus includes an additional web interface for administrators to manage users and permissions, and to perform bulk operations such as updating or deleting multiple entries at once. It looks pretty too (as seen on the right above).

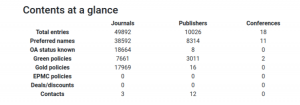

Current coverage

Orpheus includes parsers that allowed substantial datasets of journals and their attributes to be imported into the system, saving the Cambridge team the effort of populating the database from scratch. Data was imported from:

- Taylor & Francis

- Version 14 of Andrew Gray’s “Elsevier embargo periods, 2013-2018”

- Elsevier’s OA Price List

- Wiley’s “Author Compliance tool”

- Cambridge University Press

- Oxford University Press

- Directory of Open Access Journals

- Sherpa RoMEO

Orpheus currently has almost 40,000 journal entries belonging to more than 8,000 publishers (“preferred names”; the larger number of “total entries” includes synonyms).

Orpheus currently has almost 40,000 journal entries belonging to more than 8,000 publishers (“preferred names”; the larger number of “total entries” includes synonyms).

While we may derive some satisfaction in achieving comprehensive coverage and including journals such as هیدروژیولوژی and Демографија, what really matters to us in terms of maximising the efficiency of our services is databasing those journals and conferences that Cambridge academics most often publish in.

A quick analysis of journal names contained in all Apollo submissions received since 2014 (29,598 submissions) reveals that we are now able to match 83% of those to a record in Orpheus and retrieve embargo periods, APC value and licencing information for, respectively, 72, 48 and 37% of past submissions. These results are encouraging, especially considering that (1) ’journal name’ in this dataset of past submissions includes conference names and strings that do not correspond to true journals, such as 13 entries for ’TBC’ (to be completed); and (2) for new submissions, our system tries to find matches by ISSN and eISSN before attempting matches by name, so we have a better chance of matching “Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.)” to the right journal than this analysis would suggest.

Integrations with Apollo and Zendesk

Without digging into the technical details of the integration of Orpheus with Apollo (to be honest, I would not be able to go into detail here, for the integration with Apollo was fully implemented by my colleague Agustina Martinez-Garcia), it suffices to say that Apollo has been querying Orpheus and successfully applying embargoes to many of the c. 900 submissions we receive per month (we received, on average, 892 monthly submissions in 2018).

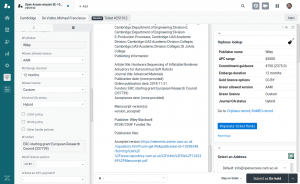

Orpheus has also been integrated with our helpdesk system (powered by Zendesk) via “Orpheus Lookup”, a small Open Source application available here. This enables relevant information about journals to be embedded in our helpdesk interface (see right hand side pane of screenshot below), facilitating the job of advising researchers on how to comply with their funders’ Open Access policies. The app also allows us to populate the relevant helpdesk ticket fields (see left hand side pane of screenshot) with one click. Information in these fields may then be processed by a Zendesk macro (also Open Source), to produce tailored auto-reply messages that can be further customised by the staff member.

Orpheus has also been integrated with our helpdesk system (powered by Zendesk) via “Orpheus Lookup”, a small Open Source application available here. This enables relevant information about journals to be embedded in our helpdesk interface (see right hand side pane of screenshot below), facilitating the job of advising researchers on how to comply with their funders’ Open Access policies. The app also allows us to populate the relevant helpdesk ticket fields (see left hand side pane of screenshot) with one click. Information in these fields may then be processed by a Zendesk macro (also Open Source), to produce tailored auto-reply messages that can be further customised by the staff member.

In summary, our experience indicates that the benefits of integration of an institutional repository with an auxiliary database providing machine-readable representations of frequently required attributes of journals, conferences and publishers outweigh the costs of development and maintenance of the system. Other institutions or consortia interested in automating the processes of looking up and applying those attributes to repository records may benefit from hosting an instance of Orpheus.

If you are interested in more detail about the Orpheus integration, please email us on info@repository.cam.ac.uk and we will be happy to help.