As part of Open Access Week 2017, the Office of Scholarly Communication is publishing a series of blog posts on open access and open research. In this post Maria Angelaki describes how challenging it can be to interpret publication dates featured on some publishers’ websites.

More than three weeks a year. That’s how much time we spend doing nothing but determining the publication date of the articles we process in the Open Access team.

To be clear about what we are talking about here: All we need to know for HEFCE compliance is when the final Version of Record was made available on the publisher’s website. Also, if there is a printed version of the journal, for our own metadata, we need to know the Issue publication date too.

Surely, it can’t be that hard.

Defining publication date

The Policy for open access in Research Excellence framework 2021 requires the deposit of author’s outputs within three months of acceptance. However, the first two years of this policy has allowed deposits as late as three months from the date of publication.

It sounds simple doesn’t it? But what does “date of publication” mean? According to HEFCE the Date of Publication of a journal article is “the earliest date that the final version-of-record is made available on the publisher’s website. This generally means that the ‘early online’ date, rather than the print publication date, should be taken as the date of publication.”

When we create a record in Apollo, the University of Cambridge’s institutional repository, we input the acceptance date, the online publication date and the publication date.

We define the “online publication date” as the earliest online date the article has appeared on the publisher’s website and “publication date” as the date the article appeared in a print issue. These two dates are important since we rely on them to set the correct embargoes and assess compliance with open access requirements.

The problems can be identified as:

- There are publishers that do not feature clearly the “online date” and the “paper issue date”. We will see examples further on.

- To make things more complicated, some publishers do not always specify which version of the article was published on the “online date”. It can variously mean the author’s accepted manuscript (AAM), corrected proof, or the Version of Record (VoR), and there are sometimes questions in the latter as to whether these include full citation details.

- Lastly, there are cases where the article is first published in a print issue and then published online. Often print publications are only identified as “Spring issue’ or the like.

How can we comply with HEFCE’s deposit timeframes if we do not have a full publication date cited in the publisher’s website? Ideally, it would only take a minute or so for anybody depositing articles in an institutional repository to find the “correct” publication date. But these confusing cases mean the minute inevitably becomes several minutes, and when you are uploading 5000 odd papers a year this turns into 17 whole days.

Setting rules for consistency

In the face of all of this ambiguity, we have had to devise a system of ‘rules’ to ensure we are consistent. For example:

- If a publication year is given, but no month or day, we assume that it was 1st January.

- If a publication year and month are given but no day, we assume that it was 1st of the month.

- If we have an online date of say, 10th May 2017 and a print issue month of May 2017, we will use the most specific date (10th May 2017) rather than assuming 1st May 2017 (though it is earlier).

- Unless the publisher specifies that the online version is the accepted manuscript, we regard it as the final VOR with or without citation details.

- If we cannot find a date from any other source, we try to check when the pdf featured on the website was created.

This last example does start to give a clue to why we have to spend so much time on the date problem.

By way of illustration, we have listed below some examples by publisher of how this affects us. This is a deliberate attempt to name and shame, but if a publisher is missing from this list, it is not because they are clear and straightforward on this topic. We just ran out of space. To be fair though, we have also listed one publisher as an example to show how simple it is to have a clear and transparent article publication history.

Taylor & Francis – ‘published online’

Publication date of an article online

There are several ways you can read an article. If the article is open access or if you subscribe, then you can download a pdf of the article from the publisher website. Otherwise, you see the online version on the website. The two versions of a particular article are below, the pdf and the online HTML version.

Both the pdf and the online version of the article list the article history as:

Received 14 March 2016

Accepted as 23 December 2016

Published online 12 January 2017

and also cite the Volume, year of publication and issue.

But does the ‘Published online’ date refer to when the Version of Record was made available online or the first time the Accepted Manuscript was made available online? We can’t distinguish this to provide the date for HEFCE.

Publication date of the printed journal

While we know the volume, year of publication and issue number, we don’t know what the exact publication date of the printed journal is for our metadata records. If we drill a bit more and we visit past volumes of the journal, we can see that the previous complete year (2016) features 12 issues. So we can make an educated guess that the issue number refers to the publication month (in our example it is issue 5, so it is May 2017).

However, we are wrong. The 12 issues refer to the online publication issues and not the print issues. According to Taylor & Francis’ agents customer service page they “have a number of journals where the print publication schedule differs to the online”. They have a list of those journals available and in our case we can see that this particular journal has 12 online issues but 4 paper issues in a year. So when did this actual article appear in print? Who knows.

Implications

Remember the 17 days a year? This is the type of activity that fills the time. Do we really need to do this time consuming exercise? Some might suggest that we contact the publisher and ask, but it is time-consuming and not always successful.

Elsevier’s Articles in Press

Elsevier’s description of Articles in Press states they are “articles that have been accepted for publication in Elsevier journals but have not yet been assigned to specific issues”. They could be any of an Accepted Manuscript, a Corrected Proof or an Uncorrected Proof. Elsevier have a page that answers questions about ‘grey areas’ and in a section discussing whether it is permissible for Elsevier to remove an article for some reason, they state they do not remove articles that have been published but “…papers made available in our “Articles in Press” (AiP) service do not have the same status as a formally published article…)”

This means the same article could be an ‘Article in Press’ in three different stages, none of which are ‘published’. Even when an article has moved beyond “In Press” mode and has been published in an issue we are not informed which version Elsevier refers to when the “available online” date is featured.

This means the same article could be an ‘Article in Press’ in three different stages, none of which are ‘published’. Even when an article has moved beyond “In Press” mode and has been published in an issue we are not informed which version Elsevier refers to when the “available online” date is featured.

Let’s look at an example. Is the ‘Available online’ date of 13 December 2016 when it was available online as an Accepted Manuscript, a Corrected Proof or an Uncorrected Proof? This is very unclear.

Let’s look at an example. Is the ‘Available online’ date of 13 December 2016 when it was available online as an Accepted Manuscript, a Corrected Proof or an Uncorrected Proof? This is very unclear.

So we have a disconnect. The earliest online date is not the final published version as per HEFCE’s requirement. There is no way of determining the date when the final published date does actually appear online, so we need to wait until the article is allocated an issue and volume for us to determine the date. This could be some considerable time AFTER the work has been finalised. So open access is delayed, we risk non compliance and waste huge amounts of time.

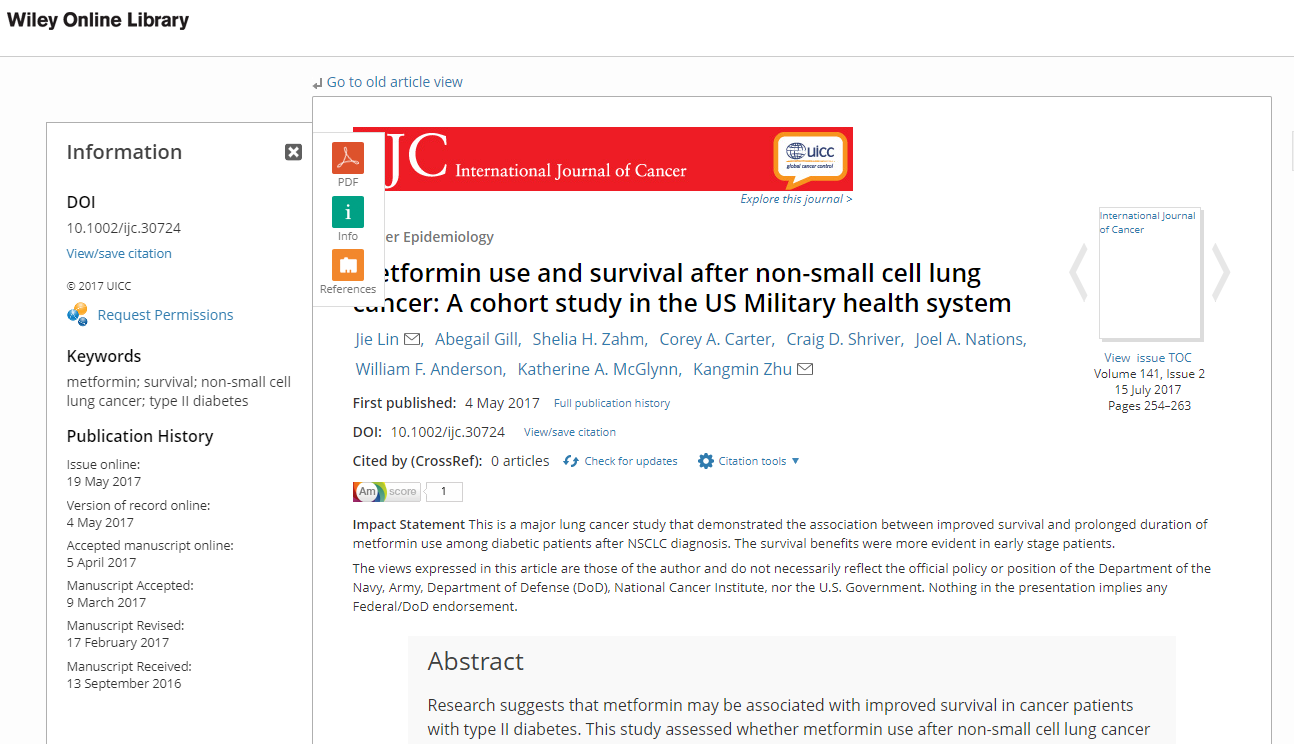

Well done, Wiley

Wiley features all possible stages of the article’s various publication stages making it easy to distinguish the VoR online publication date, exactly what HEFCE (and we) require.

Article published in an issue

This is an example of when an article is published online and the print issue is published too.

Article published online (awaiting for a print issue date)

Wiley states the publication history clearly even when an article is published online but not yet included in a publication issue.

If you have a closer look at the screenshot, Wiley regards as “First published” the VoR online publication date (shown also on the left under Publication History) and not the Accepted Manuscript online date.

In this case, the publisher clearly states which version they refer to when the term “First Published” is used and also gives the reader the full history of the article’s “life stages” as well as inform us that the article is yet not included in an issue (circle on the right).

Conclusions

If you have made it this far through the blog post, you are probably working in this area and have some experience of this issue. If you are new to the topic, hopefully the above examples have illustrated how frustrating it is sometimes to find the correct information in order to comply with not only HEFCE’s timeframe requirements, but other open access compliance issues, especially when you set embargoes.

A simple task can become an expensive exercise because we are wasting valuable working hours. We are in the business of supporting the research community to openly share research outputs, not in the business of deciphering information in publishers’ websites.

We need clear information in order to effectively deposit an article to our institutional repository and meet whatever requirements need to be met. It is not unreasonable to expect consistency and standards in the display of publication history and dates of articles.