In a sister post, I identified the latest scare offensive in the ongoing discussions around open access as: ‘restricting choice of publication’. In this, there is an implied threat from editorial boards and publishers that if the UK Scholarly Communication Licence (UKSCL) were to be in place, then these journals would refuse to publish articles from affected researchers.

In this post I want to look at other threats that have been or are lurking in the shadows in the open access debate. The first is tied fairly closely to the ‘restricting choice of publication’ threat.

The new scare – threats to ‘Academic Freedom’

The term ‘Academic Freedom’ comes up a fair bit in discussions about open access. In his tweet sent during the Researcher to Reader conference*, one of my Advisory Board colleagues Rick Anderson tweeted this comment:

“Most startling thing said to me in conversation at the #R2RConf:

“I wonder how much longer academic freedom will be tolerated in IHEs.” (Specific context: authors being allowed to choose where they publish.)

In this blog I’d like to pick up on the ‘Academic Freedom’ part of the comment (which is not Rick’s, he was quoting).

Academic Freedom, according to a summary in the Times Higher Education is primarily that “Academic freedom means that both faculty members and students can engage in intellectual debate without fear of censorship or retaliation”.

This definition was based on the American Association of University Professors’ (AAUP) Statement on Academic Freedom which includes, quite specifically, “full freedom in research and in the publication of results”.

Personally I read that as meaning academics should be allowed to publish, not that they have full freedom in choosing where.

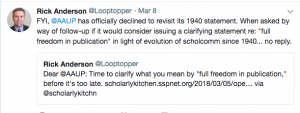

Rick has since contacted the AAUP to ask for clarification on this topic. Last Friday, he tweeted that the AAUP has declined to revisit the 1940 statement to clarify the ‘freedom in publication’ statement in light of evolution of scholarly communication since 1940.

Rick has since contacted the AAUP to ask for clarification on this topic. Last Friday, he tweeted that the AAUP has declined to revisit the 1940 statement to clarify the ‘freedom in publication’ statement in light of evolution of scholarly communication since 1940.

The reason why the Academic Freedom/ ‘restricting choice of publication’ threat(s) is so concerning to the research community has changed over time. In the past it was essential to be able to publish in specific outlets because colleagues would only read certain publications. Those publications were effectively the academic ‘voice’. However today, with online publication and search engines this argument no longer holds.

What does matter however is the publication in certain journals is necessary because of the way people are valued and rewarded. The problem is not open access, the problem is the reward system to which we are beholden. And the commercial publishing industry is fully aware of this.

So let’s be clear. Academic Freedom is about freedom of expression rather than freedom of publication outlet and ties into Robert Merton’s 1942 norms of science which are:

- “communalism”: all scientists should have common ownership of scientific goods (intellectual property), to promote collective collaboration; secrecy is the opposite of this norm.

- universalism: scientific validity is independent of the sociopolitical status/personal attributes of its participants

- disinterestedness: scientific institutions act for the benefit of a common scientific enterprise, rather than for the personal gain of individuals within them

- organized scepticism: scientific claims should be exposed to critical scrutiny before being accepted: both in methodology and institutional codes of conduct.

If a publisher is preventing a researcher from publishing in a journal based on their funding or institutional policy rather than the content of the work being submitted then this is entirely in contravention of all of Robert Merton’s norms of science. But the publisher is not, as it happens, threatening the Academic Freedom of that author.

While we are here, let’s have a quick look at some of the other threats to researchers invoked in the last few years.

Historic scare 1 – Embargoes are necessary for sustainability

In the past the publishing industry has tried to claim research on half-life usage of research articles as ‘evidence’ for the “green open access = cancellations” argument. This sounds plausible except for the lack of any causal link between green open access policies and library subscriptions. The argument here is that embargoes are necessary for the ‘sustainability’ (read profit) of commercial publishers.

We should note the British Academy’s own 2014 finding that “libraries for the most part thought that embargoes for author-accepted manuscripts had little effect on their acquisition policies” and that any real cancellation issue was “the rising cost of journals at a time of budgetary constraint for libraries. If that continues, journals will be cancelled anyway, whether posted manuscripts are available or not.”

My debunking of this claim dates back to 2015 although it did raise its head again loudly in 2017 during discussions around the UKSCL. It is not uncommon for a researcher to express concern about their chosen journal’s viability because of open access. The message has been successfully pushed through to the research community.

Historic scare 2 – The need for full copyright

Copyright is supposed to protect the content creator. The argument I hear repeatedly about why publishers need authors to sign their copyright over to publishers is so they can ‘protect the author’s rights’. But when people sign their copyright away to another entity, copyright becomes a purely economic tool for financial exploitation by that entity.

There is no doubt publishers protect their own copyright. Indeed owning it allows maximum freedom to make money from the content (and prevent anyone else from doing so). But strangely whenever I have asked for examples of publishers stepping in to protect an author’s rights as the result of a copyright transfer agreement, there has been no response.

However it is not uncommon for a researcher to tell you that this is one of the protections that publishers offer them. I defer to Lizzie Gadd here who has published thoughts around the distinctions between copyright culture and scholarly culture. She notes how many academics have been led by publishers to believe that the current copyright culture supports scholarly culture to a far greater extent than it actually does.

Historic scare 3 – Press embargoes

The HEFCE open access policy requires the collection and deposit of work within three months of acceptance (although the first two years of the policy pushed this timeline out to three months from publication). This means that work is deposited into repositories, and the metadata that exists – the title, the authors, the intended journal and the abstract – is made available before publication. The work itself (and we are talking about the Author’s Accepted Manuscript, not the final Version of Record) is under an infinite embargo which will be set when the work is published. This process has its own problems, discussed elsewhere.

In 2016 there was a blow up about the metadata about an article being in the public domain before publication. Our office received multiple concerned calls by researchers asking us to remove records from the repository until publication because of fear that having that metadata available was in contravention of the embargo rules. They were concerned the journal would refuse to publish their paper. When we investigated, not only was this not publisher policy but if anyone had been threatened in this manner the publishers we contacted requested we forward the information so they could follow up.

It demonstrates how spooked academics can be by their editors/journals/publishers.

Exhausting

This latest ‘restricting choice of publication’ threat is just another in a long line of implied threats that the scholarly communication community is having to manage. Each time a new one looms we need to identify the source, develop evidence and information to counter the threat and try and work with our research community to reassure them.

Between this, and the huge amount of time we have to spend identifying dates of publication or managing publisher and funder policies or keeping track of the funds that are being spent in this space, we are exhausted.

But perhaps that’s the point?

Published 15 March 2018

Written by Dr Danny Kingsley

* Note: In the past two years I have written a precis up about the Researcher to Reader event with summaries, see: ‘It is all a bit of a mess’ Observations from Researcher to Reader conference and ‘Be nice to each other’ – the second Researcher to Reader conference. Time pressure means I may not be able to do that this year, but see the Twitter hashtag for the event.