Dr Mandy Wigdorowitz, Open Research Community Manager, Cambridge University Libraries

On Friday 17 November 2023, participants from across Cambridge and beyond gathered for a hybrid meeting on Open Research from different perspectives. Hosted by Cambridge University Libraries at Downing College, ‘Open Research for Inclusion: Spotlighting Different Voices in Open Research at Cambridge‘ drew attention to different areas of Open Research that have been at the forefront of recent discussions in Cambridge by showcasing the scope and breadth of open practices in typically under-represented disciplines and contexts. These included the Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences, the GLAM sector (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums), and research from and about the Global South. A total of 84 in-person and 75 online attendees participated in the day-long event consisting of a keynote address, two talks, two panels, and a workshop.

The conference opened with a welcome address from Professor Anne Ferguson-Smith CBE FRS FMedSci, Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Research and International Partnerships and the Arthur Balfour Professor of Genetics. Professor Ferguson-Smith emphasised the significance and timeliness of the conference and how it underscores the importance of the Open Research movement. She encouraged attendees to be open to new ideas, approaches, and perspectives that center around Open Research and to celebrate the richness of diversity in research.

Our keynote speaker, Dr Siddharth Soni, Isaac Newton Trust Fellow at Cambridge Digital Humanities and affiliated lecturer at the Faculty of English, then addressed the audience with a talk on Common Ground, Common Duty: Open Humanities and the Global South, providing an account of how to think against neoliberal conceptions of ‘open’ and to reimagine what openness might look like if the Global South was viewed as a common ground space for building an open and international university culture. Dr Soni’s address set the tone for a rich, multi-layered exploration of Open Research on the day, urging attendees to think of open humanities as a form of knowledge that seeks to alter the form and content of knowledge systems rather than just opening Euro-American knowledge systems to global publics.

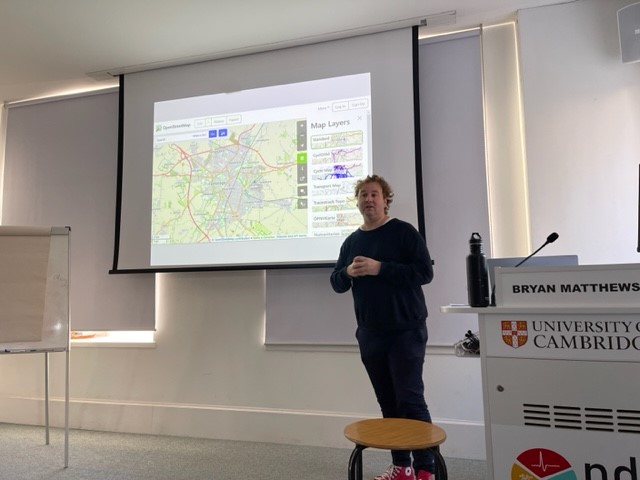

The next talk was from Dr Stefania Merlo from the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research and Dr Rebecca Roberts from the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research and Fitzwilliam Museum who further explored the theme of the Global South in their practical perspective on how they managed the curation of digital archives for heritage management from their work on the projects: Mapping Africa’s Endangered Archaeological Sites and Monuments (MAEASaM) and Mapping Archaeological Heritage in South Asia (MAHSA). They reflected on the opportunities and challenges relating to the production and dissemination of information about archaeological sites and monuments in projects across Africa and South Asia as well as their experience working with and learning from local communities.

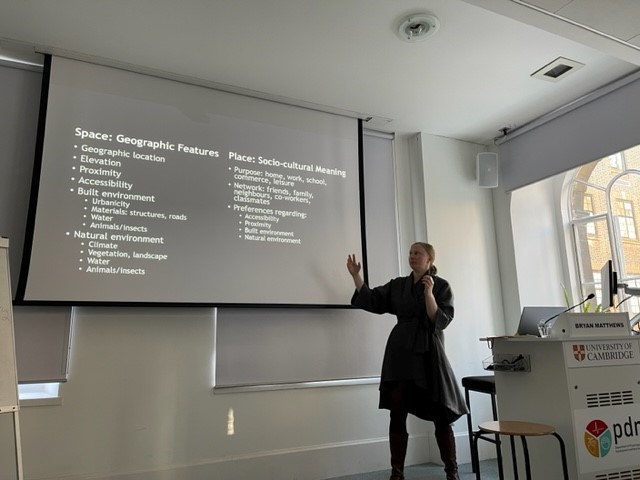

An Open Research panel session was next which featured panellists with diverse backgrounds and expertise who addressed registrants’ pre-submitted and live questions. Some questions included the meaning of Open Research, its advantages and challenges, how Open Research can be engaged with by researchers (and in particular, early career researchers), and how it can be rewarded and embedded into the culture of research practices. There was engaging insights and debate amongst the panellists, led by Bertrand Russell Professor of Philosophy, Professor Alexander Bird. He shared the platform with Philosophy of Science Professor, Professor Anna Alexandrova, Psychiatry PhD student Luisa Fassi, Cambridge University Libraries (CUL) Interim Head of Open Research Services Dr Sacha Jones, Cambridge University Press & Assessment’s Research Data Manager Dr Kiera McNeice, and Cambridge’s Head of Research Culture Liz Simmonds.

Following lunch, a second panel of scholars working across the GLAM sector (Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums) took place. The panel was chaired by CUL’s Scholarly Communication Specialist, Dr Samuel Moore, and brought together experts who showcased their diverse work in this sector, from software development and museum practices to infrastructure and archiving support. The panel included Dr Mary Chester-Kadwell, CUL’s Senior Software Developer and Lead Research Software Engineer at Cambridge Digital Humanities, Isaac Newton Trust Research Associate in Conservation Dr Ayesha Fuentes from the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Dr Agustina Martinez-Garcia, CUL’s Head of Open Research Systems, and Dr Amelie Roper, CUL’s Head of Research. Each panellist presented on a specialist area, including Open Research code and data practices in digital humanities, collections research, teaching and learning collections care, and Open Research infrastructure. A lively discussion followed from the presentations.

In a workshop session, Tim Fellows, Product Manager for Octopus, outlined how Octopus is a free and alternative publishing model that can practically foster Open Research. The platform, funded by UKRI, is designed for researchers to share ‘micro publications’ that more closely represent how research is conducted at each stage of a project. In a demonstration of the platform, Tim Fellows showed how Octopus works, it’s design, user interface, and application all with the aim of aiding reproducibility, facilitating new ways of sharing research, and removing barriers to both publishing and accessing research. An in-depth discussion followed which centered on the ways the platform can be used as well as its uptake and application across various disciplines.

The final talk of the day was on Open Research and the coloniality of knowledge presented by Professor Joanna Page, Director of CRASSH and Professor of Latin American Studies. She discussed the topic with a specific focus on the questions of possession and access by outlining projects by three Latin American artists who have engaged with Humboldt’s legacy and the coloniality of knowledge. Using videos and imagery, Professor Page encouraged the audience to consider how they might identify where the principles of Open Research conflict with those of inclusion and cognitive justice, and what might be done to reconcile those ambitions across diverse cultures and communities. An engaging discussion ensued.

A drinks reception brought the event to a close, allowing attendees a chance to mingle, network and continue the discussions.

Special thanks to all speakers, attendees, and volunteers for making this event such a success. Stay tuned for information about our 2024 Open Research conference.